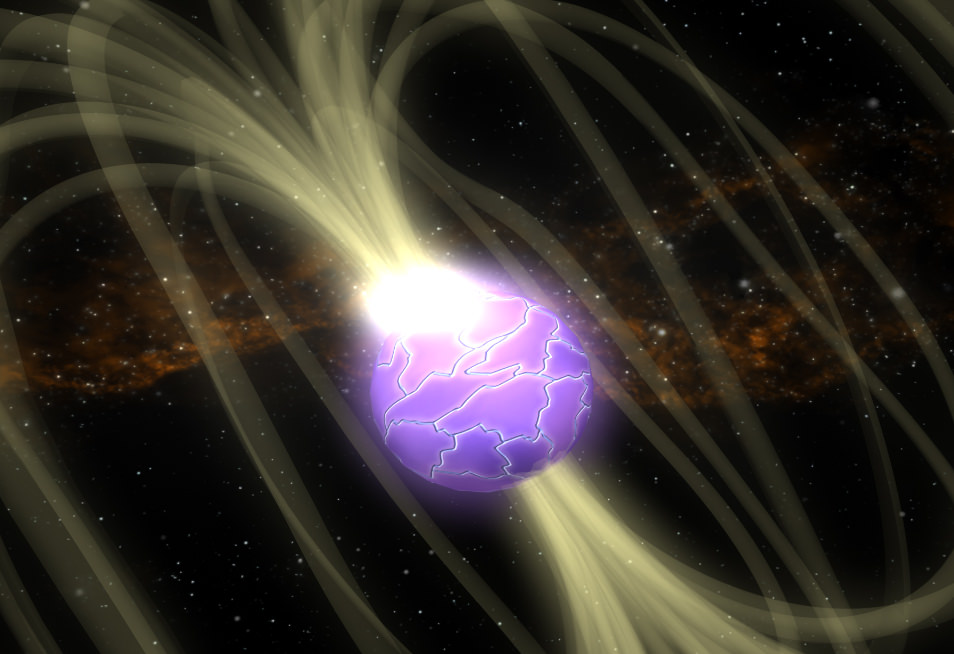

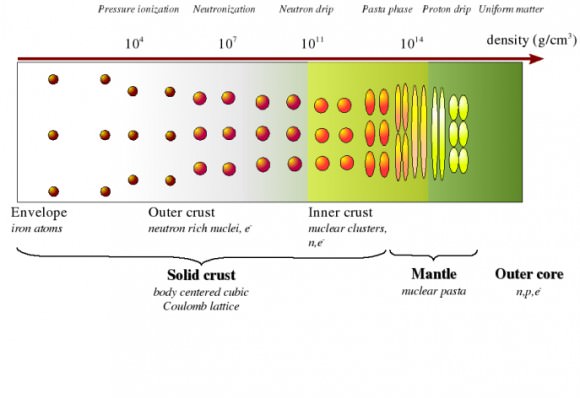

The upper crust of a neutron star is thought to be composed of crystallized iron, may have centimeter high mountains and experiences occasional ‘star quakes’ which may precede what is technically known as a glitch. These glitches and the subsequent post-glitch recovery period may offer some insight into the nature and behavior of the superfluid core of neutron stars.

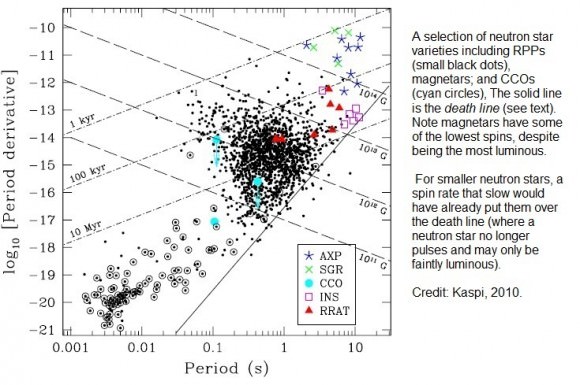

The events leading up to a neutron star quake go something like this. All neutron stars tend to ‘spin down’ during their life cycle, as their magnetic field applies the brakes to the star’s spin. Magnetars, having particularly powerful magnetic fields, experience more powerful braking.

During this dynamic process, two conflicting forces operate on the geometry of the star. The very rapid spin tends to push out the star’s equator, making it an oblate spheroid. However, the star’s powerful gravity is also working to make the star conform to hydrostatic equilibrium (i.e. a sphere).

Thus, as the star spins down, its crust – which is reportedly 10 billion times the strength of steel – tends to buckle but not break. There may be a process like a tectonic shifting of crustal plates – which create ‘mountains’ only centimeters high, although from a base extending for several kilometres over the star’s surface. This buckling may relieve some of stresses the crust is experiencing – but, as the process continues, the tension builds up and up until it ‘gives’ suddenly.

The sudden collapse of a 10 centimeter high mountain on the surface of a neutron star is considered to be a possible candidate event for the generation of detectable gravitational waves – although this is yet to be detected. But, even more dramatically, the quake event may be either coupled with – or perhaps even triggered by – a readjustment in the neutron’s stars magnetic field.

It may be that the tectonic shifting of crustal segments works to ‘wind ‘up’ the magnetic lines of force sticking out past the neutron star’s surface. Then, in a star quake event, there is a sudden and powerful energy release – which may be a result of the star’s magnetic field dropping to a lower energy level, as the star’s geometry readjusts itself. This energy release involves a huge flash of x and gamma rays.

In the case of a magnetar-type neutron star, this flash can outshine most other x-ray sources in the universe. Magnetar flashes also pump out substantial gamma rays – although these are referred to as soft gamma ray (SGR) emissions to distinguish them from more energetic gamma ray bursts (GRB) resulting from a range of other phenomena in the universe.

However, ‘soft’ is a bit of a misnomer as either burst type will kill you just as effectively if you are close enough. The magnetar SGR 1806-20 had one of largest (SGR) events on record in December 2004.

Along with the quake and the radiation burst, neutron stars may also experience a glitch – which is a sudden and temporary increase in the neutron star’s spin. This is partly a result of conservation of angular momentum as the star’s equator sucks itself in a bit (the old ‘skater pulls arms in’ analogy), but mathematical modeling suggests that this may not be sufficient to fully account for the temporary ‘spin up’ associated with a neutron star glitch.

González-Romero and Blázquez-Salcedo have proposed that an internal readjustment in the thermodynamics of the superfluid core may also play a role here, where the initial glitch heats the core and the post-glitch period involves the core and the crust achieving a new thermal equilibrium – at least until the next glitch.