[/caption]

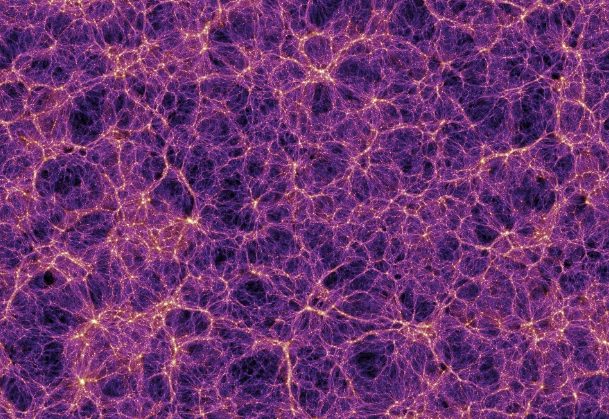

There’s a growing view that black holes in the early universe may have been the seeds around which most of today’s big galaxies (now with supermassive black holes within) first grew. And taking a step further back, it might also be the case that black holes were key to reionizing the early interstellar medium – which then influenced the large scale structure of today’s universe.

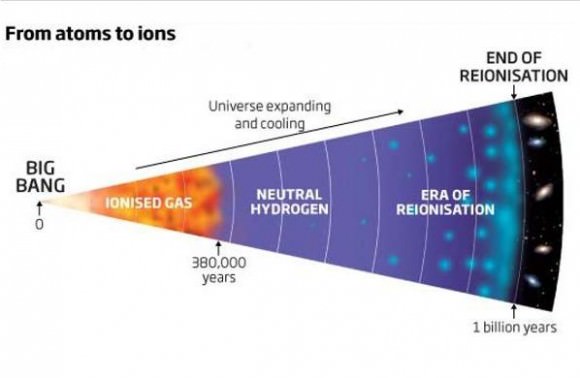

To recap those early years… First was the Big Bang – and for about three minutes everything was very compact and hence very hot – but after three minutes the first protons and electrons formed and for the next 17 minutes a proportion of those protons interacted to form helium nuclei – until at 20 minutes after the Big Bang, the expanding universe became too cool to maintain nucleosynthesis. From there, the protons and the helium nuclei and the electrons just bounced around for the next 380,000 years as a very hot plasma.

There were photons too, but there was little chance for these photons to do anything much except be formed and then immediately reabsorbed by an adjacent particle in that broiling hot plasma. But at 380,000 years, the expanding universe cooled enough for the protons and the helium nuclei to combine with electrons to form the first atoms – and suddenly the photons were left with empty space in which to shoot off as the first light rays – which today we can still detect as the cosmic microwave background.

What followed was the so-called dark ages until around half a billion years after the Big Bang, the first stars began to form. It’s likely that these stars were big, like really big, since the cool, stable hydrogen (and helium) atoms available readily aggregated and accreted. Some of these early stars may have been so big that they quickly blew themselves to pieces as pair-instability supernovae. Others were just very big and collapsed into black holes – many of them having too much self-gravity to permit a supernova explosion to blow any material out from the star.

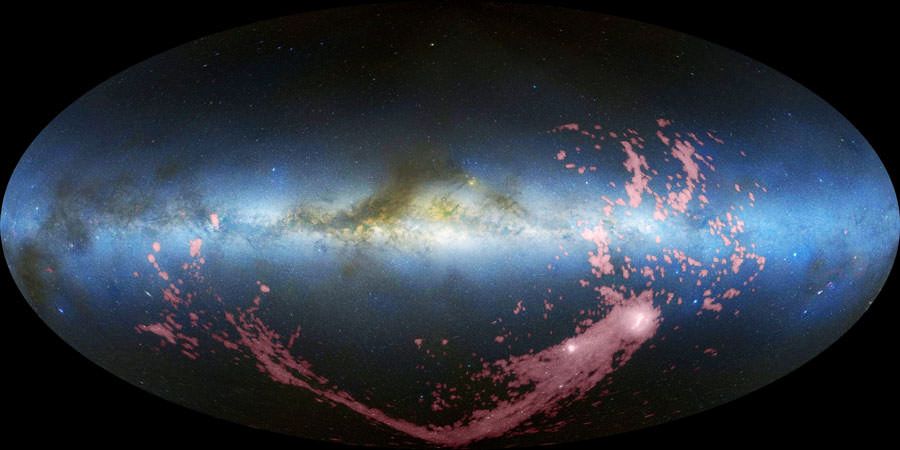

And it’s about here that the reionization story starts. The cool, stable hydrogen atoms of the early interstellar medium didn’t stay cool and stable for very long. In a smaller universe full of densely-packed massive stars, these atoms were quickly reheated, causing their electrons to dissociate and their nuclei to become free ions again. This created a low density plasma – still very hot, but too diffuse to be opaque to light any more.

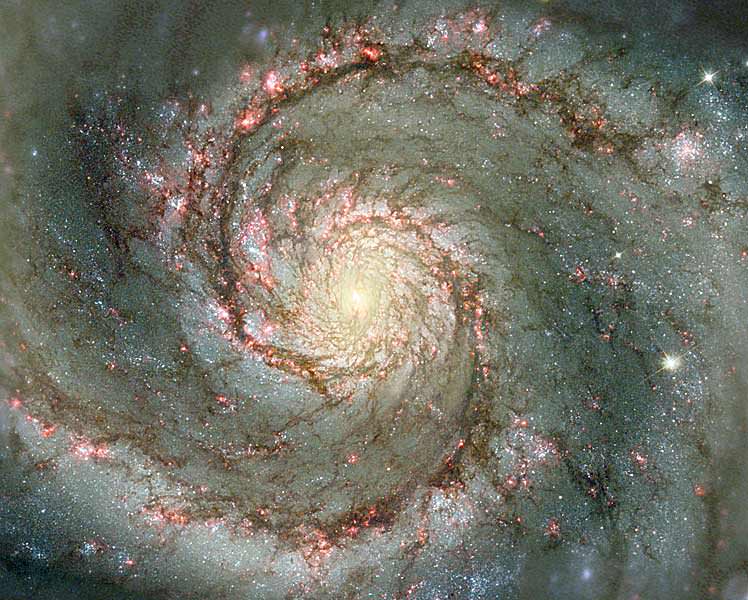

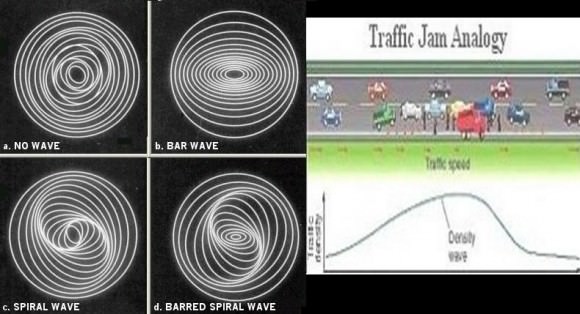

It’s likely that this reionization step then limited the size to which new stars could grow – as well as limiting opportunities for new galaxies to grow – since hot, excited ions are less likely to aggregate and accrete than cool, stable atoms. Reionization may have contributed to the current ‘clumpy’ distribution of matter – which is organized into generally large, discrete galaxies rather than an even spread of stars everywhere.

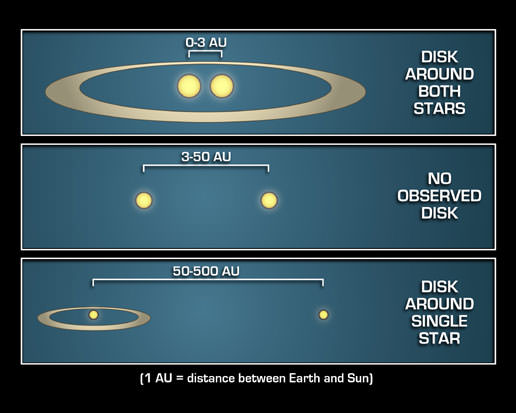

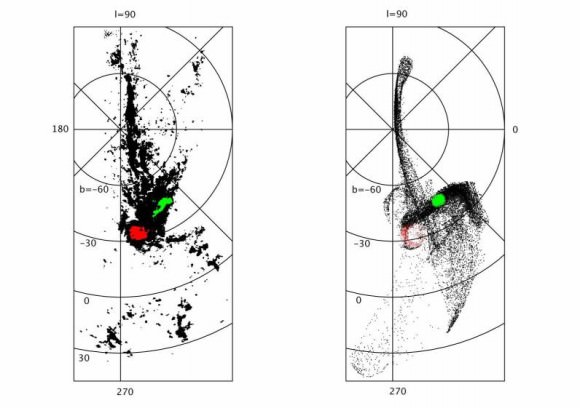

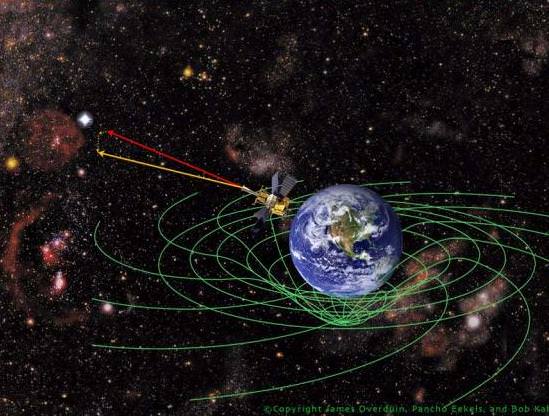

And it’s been suggested that early black holes – actually black holes in high mass X-ray binaries – may have made a significant contribution to the reionization of the early universe. Computer modelling suggests that the early universe, with a tendency towards very massive stars, would be much more likely to have black holes as stellar remnants, rather than neutron stars or white dwarfs. Also, those black holes would more often be in binaries than in isolation (since massive stars more often form multiple systems than do small stars).

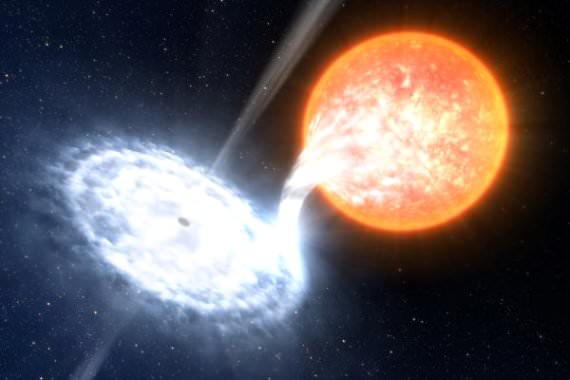

So with a massive binary where one component is a black hole – the black hole will quickly begin to accumulate a large accretion disk composed of matter drawn from the other star. Then that accretion disk will begin to radiate high energy photons, particularly at X-ray energy levels.

While the number of ionizing photons emitted by an accreting black hole is probably similar to that of its bright, luminous progenitor star, it would be expected to emit a much higher proportion of high energy X-ray photons – with each of those photons potentially heating and ionizing multiple atoms in its path, while a luminous star’s photon’s might only reionize one or two atoms.

So there you go. Black holes… is there anything they can’t do?

Further reading: Mirabel et al Stellar black holes at the dawn of the universe.