[/caption]

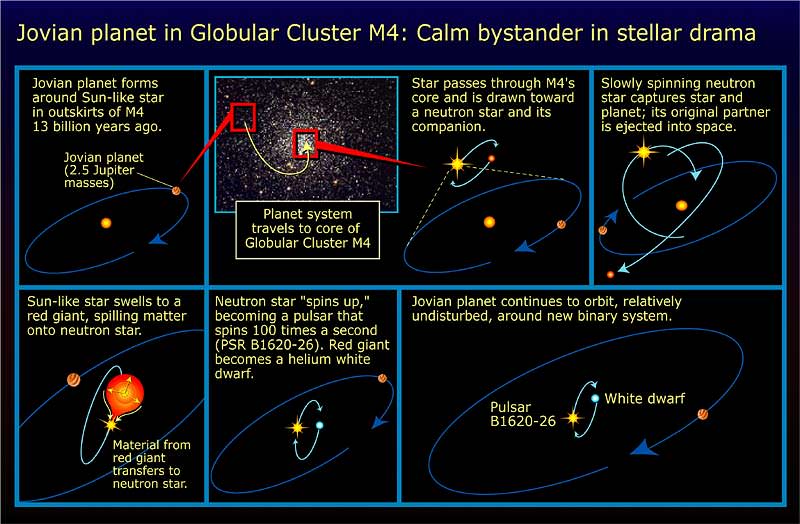

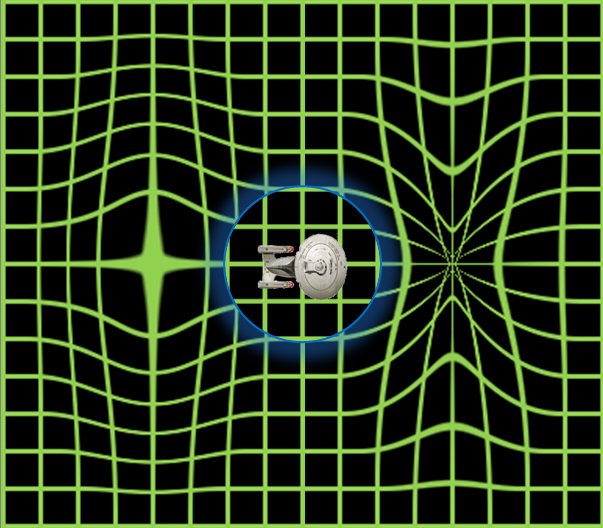

Binary star systems can have planets – although these are generally assumed to be circumbinary (where the orbit encircles both stars). As well as the fictional examples of Tatooine and Gallifrey, there are real examples of PSR B1620-26 b and HW Virginis b and c – thought to be cool gas giants with several times the mass of Jupiter, orbiting several astronomical units out from their binary suns.

Planets in circumstellar orbits around a single star within a binary system are traditionally considered to be unlikely due to the mathematical implausibility of maintaining a stable orbit through the ‘forbidden’ zones – which result from gravitational resonances generated by the motion of the binary stars. The orbital dynamics involved should either fling a planet out of the system or send it crashing to its doom into one or other of the stars. However, there may be a number of windows of opportunity available for ‘next generation’ planets to form at later stages in the evolving life of a binary system.

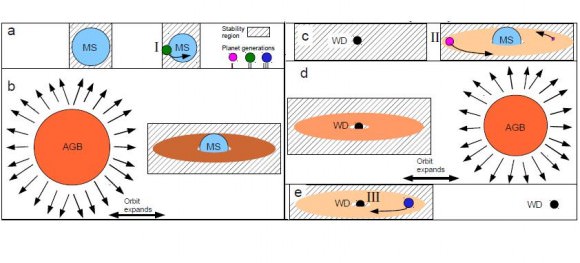

A binary stellar evolution scenario might go something like this:

1) You start with two main sequence stars orbiting their common centre of mass. Circumstellar planets may only achieve stable orbits very close in to either star. If present at all, it’s unlikely these planets would be very large as neither star could sustain a large protoplanetary disk given their close proximity.

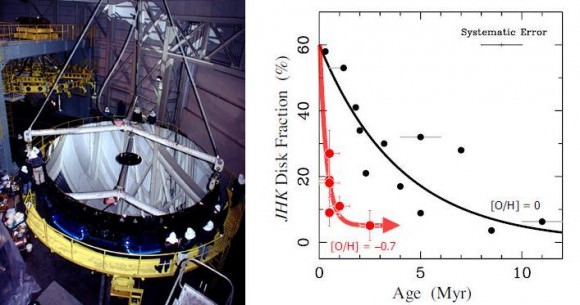

2) The more massive of the binaries evolves further to become an Asymptotic Giant Branch star (i.e. red giant) – potentially destroying any planets it may have had. Some mass is lost from the system as the red giant blows off its outer layers – which is likely to increase the separation of the two stars. But this also provides material for a protoplanetary disk to form around the red giant’s binary companion star.

3) The red giant evolves into white dwarf, while the other star (still in main sequence and now with extra fuel and a protoplanetary disk) can develop a system of orbiting ‘second generation’ planets. This new stellar system could remain stable for a billion years or more.

4) The remaining main sequence star eventually goes red giant, potentially destroying its planets and further widening the separation of the two stars – but it also may contribute material to form a protoplanetary disk around the distant white dwarf star, providing the opportunity for third generation planets to form there.

The development of the third generation planetary system depends on the white dwarf star sustaining a mass below its Chandrasekhar limit (being about 1.4 solar masses – depending on its rate of spin) despite it having received more material from the red giant. If it doesn’t stay below that limit, it will become a Type 1a supernova – potentially lobbing a small proportion of its mass back to the other star again, although by this stage that other star would be a very distant companion.

An interesting feature of this evolutionary story is that each generation of planets is built from stellar material with a sequentially increasing proportion of ‘metals’ (elements heavier than hydrogen and helium) as the material is cooked and re-cooked within each stars’ fusion processes. Under this scenario, it becomes feasible for old stars, even those which formed as low metal binaries, to develop rocky planets later in their lifetimes.

Further reading: Perets, H.B. Planets in evolved binary systems.