Welcome back to Constellation Friday! Today, in honor of the late and great Tammy Plotner, we will be dealing with the “big dog” itself – the Canis Major constellation!

In the 2nd century CE, Greek-Egyptian astronomer Claudius Ptolemaeus (aka. Ptolemy) compiled a list of all the then-known 48 constellations. This treatise, known as the Almagest, would be used by medieval European and Islamic scholars for over a thousand years to come, effectively becoming astrological and astronomical canon until the early Modern Age.

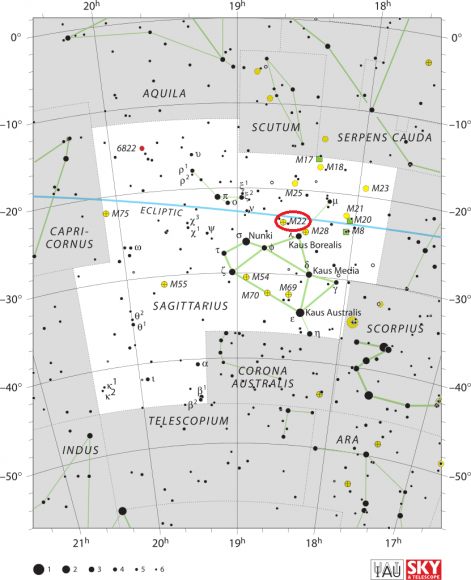

One of these constellations included in Ptolemy’s collection was Canis Major, an asterism located in the southern celestial hemisphere. As one of two constellations representing “the dogs” (which are associated with “the hunter” Orion) this constellation contains many notable stars and Deep Sky Objects. Today, it is one of the 88 constellations recognized by the IAU, and is bordered by Monoceros, Lepus, Columba and Puppis.

Name and Meaning:

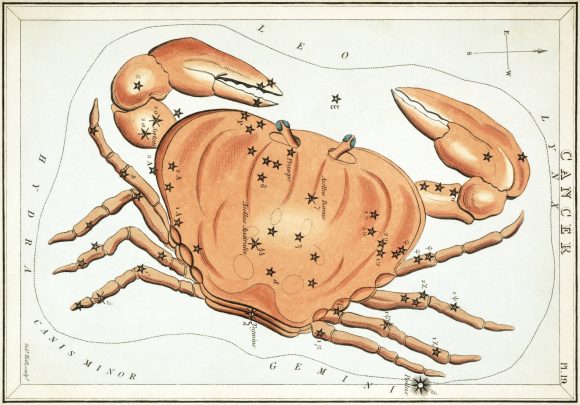

The constellation of Canis Major literally translates to “large dog” in Latin. The first recorded mentions of any of the stars associated with this asterism are traced back to Ancient Mesopotamia, where the Babylonians recorded its existence in their Three Star Each tablets (ca. 1100 BCE). In this account, Sirus (KAK.SI.DI) was seen as the arrow aimed towards Orion, while Canis Major and part of Puppis were seen as a bow.

To the ancient Greeks, Canis Major represented a dog following the great hunter Orion. Named Laelaps, or the hound of Prociris in some accounts, this dog was so swift that Zeus elevated it to the heavens. Its Alpha star, Sirius, is the brightest object in the sky (besides the Sun, the Moon and nearest planets). The star’s name means “glowing” or “scorching” in Greek, since the summer heat occurred just after Sirius’ helical rising.

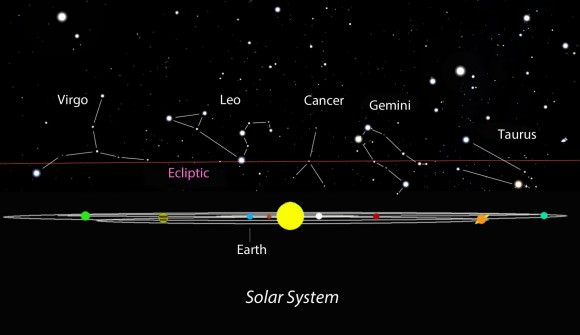

The Ancient Greeks referred to such times in the summer as “dog days”, as only dogs would be mad enough to go out in the heat. This association is what led to Sirius coming to be known as the “Dog Star”. Depending on the faintness of stars considered, Canis Major resembles a dog facing either above or below the ecliptic. When facing below, since Sirius was considered a dog in its own right, early Greek mythology sometimes considered it to be two headed.

Together with the area of the sky that is deserted (now considered as the new and extremely faint constellations Camelopardalis and Lynx), and the other features of the area in the Zodiac sign of Gemini (i.e. the Milky Way, and the constellations Gemini, Orion, Auriga, and Canis Minor), this may be the origin of the myth of the cattle of Geryon, which forms one of The Twelve Lab ours of Heracles.

Sirius has been an object of wonder and veneration to all ancient peoples throughout human history. In fact, the Arabic word Al Shi’ra resembles the Greek, Roman, and Egyptian names suggesting a common origin in Sanskrit, in which the name Surya (the Sun God) simply means the “shining one.” In the ancient Vedas this star was known as the Chieftain’s star; and in other Hindu writings, it is referred to as Sukra – the Rain God, or Rain Star.

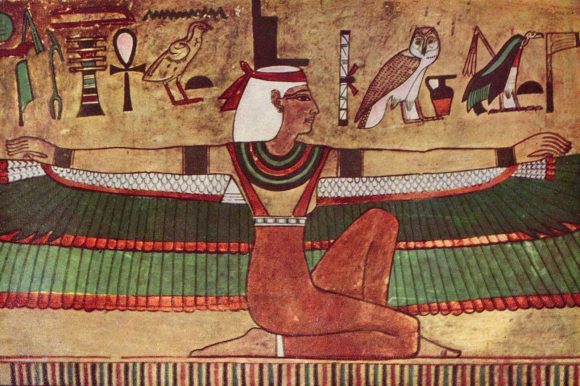

Sirius was revered as the Nile Star, or Star of Isis, by the ancient Egyptians. Its annual appearance just before dawn at the Summer Solstice heralded the flooding of the Nile, upon which Egyptian agriculture depended. This helical rising is referred to in many temple inscriptions, where the star is known as the Divine Sepat, identified as the soul of Isis.

To the Chinese, the stars of Canis Major were associated with several different asterisms – including the Military Market, the Wild Cockerel, and the Bow and Arrow. All of these lay in the Vermilion Bird region of the zodiac, on of four symbols of the Chinese constellations, which is associated with the South and Summer. In this tradition, Sirius was known Tianlang (which means “Celestial Wolf”) and denoted invasion and plunder.

This constellation and its most prominent stars were also featured in the astrological traditions of the Maori people of New Zealand, the Aborigines of Australia, and the Polynesians of the South Pacific.

History of Observation:

This constellation was one of the original 48 that Ptolemy included in his 2nd century BCE work the Amalgest. It would remain a part of the astrological traditions of Europe and the Near East for millennia. The Romans would later add Canis Minor, appearing as Orion’s second dog, using stars to the north-west of Canis Major.

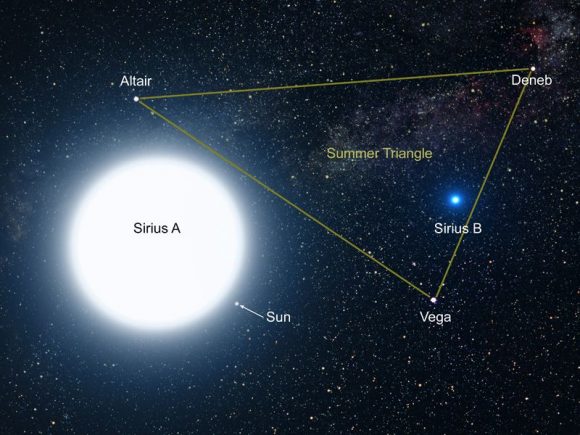

In medieval Arab astronomy, the constellation became Al Kalb al Akbar, (“the Greater Dog”), which was transcribed as Alcheleb Alachbar by European astronomers by the 17th century. In 1862, Alvan Graham Clark, Jr. made an interesting discovery while testing an 18″ refractor telescope at the Dearborn Observatory at Northwestern University in Illinois.

In the course of observing Sirius, he discovered that the bright star had a faint companion – a white dwarf later named Sirius B (sometimes called “the Pup”). These observations confirmed what Friedrich Bessel proposed in 1844, based on measurements of Sirius A’s wobble. In 1922, the International Astronomical Union would include Canis Major as one of the 88 recognized constellations.

Notable Features:

Canis Major has several notable stars, the brightest being Sirius A. It’s luminosity in the night sky is due to its proximity (8.6 light years from Earth), and the fact that it is a magnitude -1.6 star. Because of this, it produces so much light that it often appears to be flashing in vibrant colors, an effect caused by the interaction of its light with our atmosphere.

Then there’s Beta Canis Majoris, a variable magnitude blue-white giant star whose traditional name (Murzim) means the “The Heralder”. It is a Beta Cephei variable star and is currently in the final stages of using its hydrogen gas for fuel. It will eventually exhaust this supply and begin using helium for fuel instead. Beta Canis Majoris is located near the far end of the Local Bubble – a cavity in the local Interstellar medium though which the Sun is traveling.

Next up is Eta Canis Majoris, known by its traditional name as Aludra (in Arabic, “al-aora”, meaning “the virgin”). This star shines brightly in the skies in spite of its distance from Earth (approx. 2,000 light years from Earth) due to it being many times brighter (absolute magnitude) than the Sun. A blue supergiant, Aludra has only been around a fraction of the time of our Sun, yet is already in the last stages of its life.

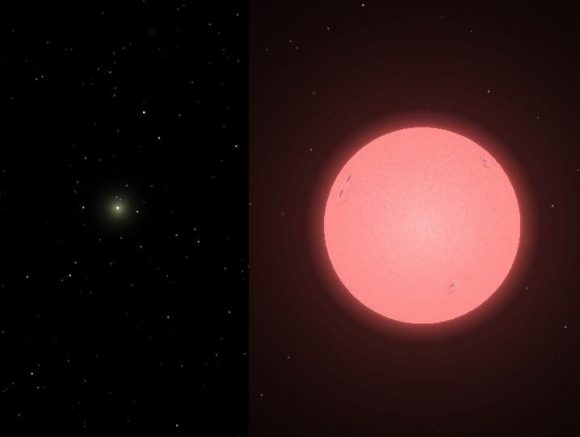

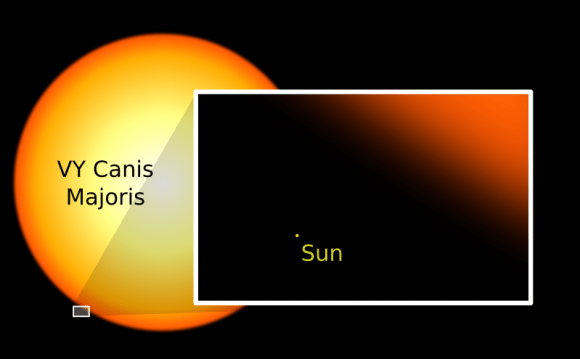

Another “major” star in this constellation is VY Canis Majoris (VY CMa), a red hypergiant star located in the constellation Canis Major. In addition to being one of the largest known stars, it is also one of the most luminous ever observed. It is located about 3,900 light years (~1.2 kiloparsecs) away from Earth and is estimated to have 1,420 solar radii.

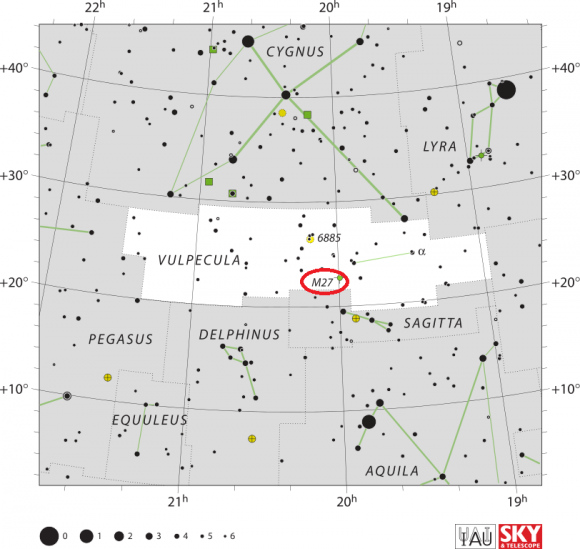

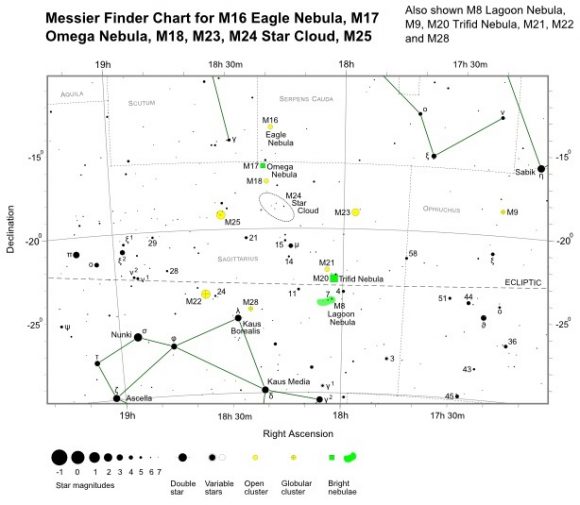

Canis Major is also home to several Deep Sky Objects, the most notable being Messier 41 (NGC 2287). Containing about 100 stars, this impressive star cluster contains several red giant stars. The brightest of these is spectral type K3, and located near M41’s center. The cluster is estimated to be between 190 and 240 million years old, and its is believed to be 25 to 26 light years in diameter.

Then there’s the galactic star cluster NGC 2362. First seen by Giovanni Hodierna in 1654 and rediscovered William Herschel in 1783, this magnificent star cluster may be less than 5 million years old and show shows signs of nebulosity – the remains of the gas cloud from which it formed. What makes it even more special is the presence of Tau Canis Major.

Easily distinguished as the brightest star in the cluster, Tau is a luminous supergiant of spectral type O8. With a visual magnitude of 4.39, it is 280,000 times more luminous than Sol. Tau CMa is also brighter component of a spectroscopic binary and studies of NGC 2362 suggest that it will survive longer than the Pleiades cluster (which will break up before Tau does), but not as long as the Hyades cluster.

Then there’s NGC 2354, a magnitude 6.5 star cluster. While it will likely appear as a small, hazy patch to binoculars, NGC 2354 is actually a rich galactic cluster containing around 60 metal-poor members. As aperture and magnification increase, the cluster shows two delightful circle-like structures of stars.

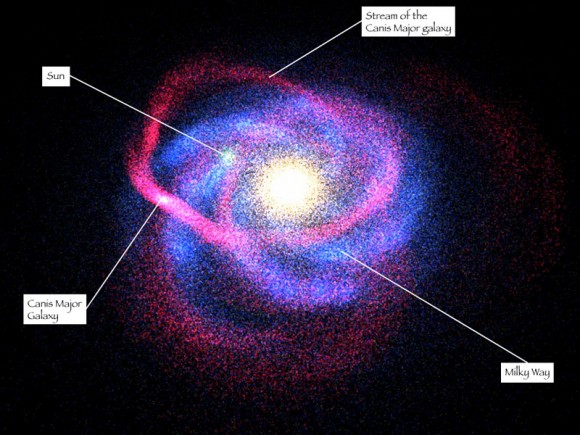

For large telescopes and GoTo telescopes, there are several objects worth studying, like the Canis Major Dwarf Galaxy (RA 7 12 30 Dec -27 40 00). An irregular galaxy that is now thought to be the closest neighboring galaxy to our part of the Milky Way, it is located about 25,000 light-years away from our Solar System and 42,000 light-years from the Galactic Center.

It has a roughly elliptical shape and is thought to contain as many stars as the Sagittarius Dwarf Elliptical Galaxy, which was discovered in 2003 and thought to be the closest galaxy at the time. Although closer to the Earth than the center of the galaxy itself, it was difficult to detect because it is located behind the plane of the Milky Way, where concentrations of stars, gas and dust are densest.

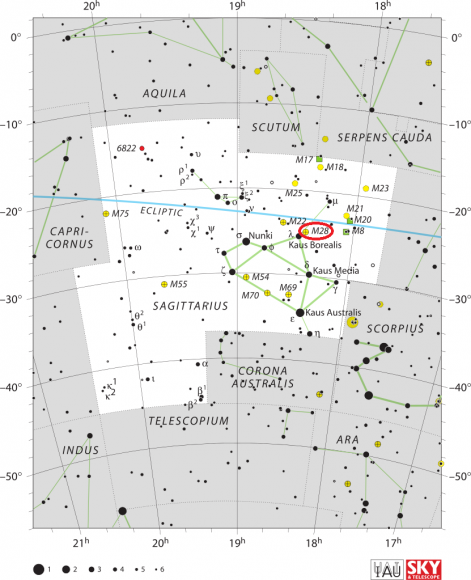

Globular clusters thought to be associated with the Canis Major Dwarf galaxy include NGC 1851, NGC 1904, NGC 2298 and NGC 2808, all of which are likely to be a remnant of the galaxy’s globular cluster system before its accretion (or swallowing) into the Milky Way. NGC 1261 is another nearby cluster, but its velocity is different enough from that of the others to make its relation to the system unclear.

Finding Canis Major:

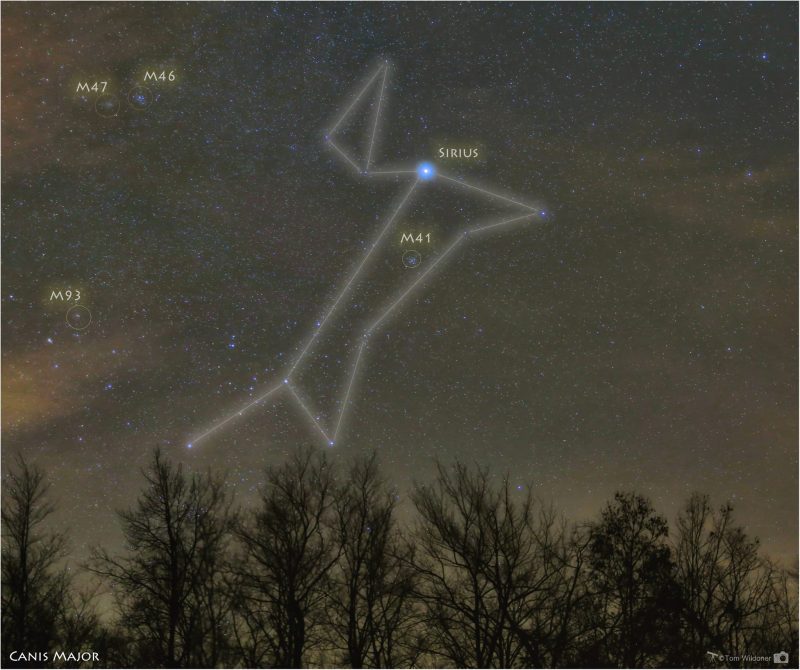

Finding Canis Major is quite easy, thanks to the presence of Sirius – the brightest star to grace the night sky. All you need to do is find Orion’s belt, discern the lower left edge of constellation (the star Kappa Orionis, or Saiph), and look south-west a few degrees. There, shining in all it glory, will be the “Dog Star”, with all the other stars stemming outwards from it.

Unfortunately, Sirius A’s luminosity means that the means that poor “Pup” hardly stands a chance of being seen. At magnitude 8.5 it could easily be caught in binoculars if it were on its own. To find it, you’ll need a mid-to-large telescope with a high power eyepiece and good viewing conditions – a stable evening (not night) when Sirius is as high in the sky as possible. It will still be quite faint, so spotting it will take time and patience.

Between Sirius at the northern tip, and Adhara at the south, you can also spot M41 residing almost about halfway. Using binoculars or telescopes, all one need do is aim about 4 degrees south of Sirius – about one standard field of view for binoculars, about one field of view for the average telescope finderscope, and about 6 fields of view for the average wide field, low power eyepiece.

Thousands of years later, Canis Major remains an important part of our astronomical heritage. Thanks largely to Sirius, for burning so brightly, it has always been seen as a significant cosmological marker. But as our understanding of the cosmos has improved (not to mention our instruments) we have come to find just how many impressive stars and stellar objects are located in this region of space.

We have written many interesting articles about the constellation here at Universe Today. Here is What Are The Constellations?, What Is The Zodiac?, and Zodiac Signs And Their Dates.

Be sure to check out The Messier Catalog while you’re at it!

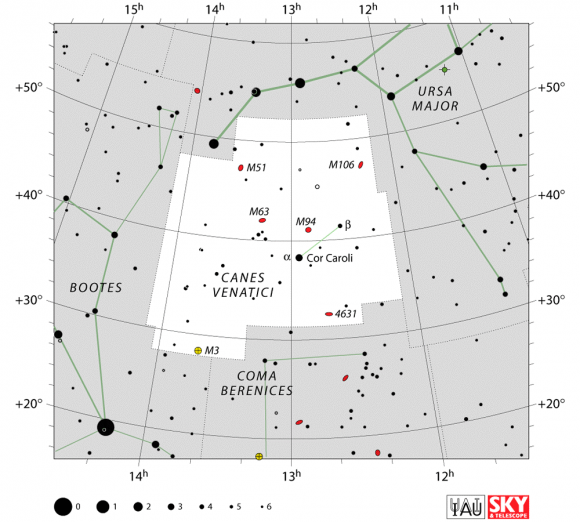

For more information, check out the IAUs list of Constellations, and the Students for the Exploration and Development of Space page on Canes Venatici and Constellation Families.

Sources:

- Wikipedia – Canis Major

- SEDS – Canis Major

- IAU – Canis Major

- Constellation Guide – Canis Major

- Chandra – Canis Major