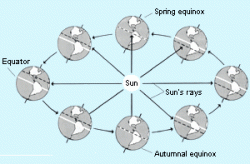

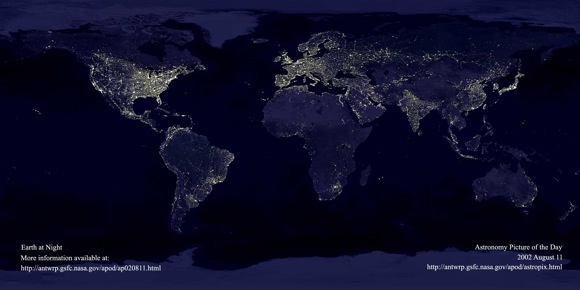

Spring officially arrives for everyone, including astronomers on March 20. The word “Equinox” literally means “equal night”. It’s all about the balance of light – not the myth of balancing eggs. On Thursday, both the day and night are the same length. But what’s so special about it? It’s a date that most of us recognize as symbolic of changing seasons. North of Earth’s equator we welcome Spring, while people south of the equator are gearing up for the cooler temperatures of Autumn.

These all too brief, but monumental moments in Earth-time, owe their significance to the slightly more than 23 degree tilt of the Earth’s axis. Because of our planetary angle, we receive the Sun’s rays most directly during the Summer. In the Winter, when we are tilted away from the Sun, the rays pass through the atmosphere at a greater slant, bringing lower temperatures. If the Earth rotated on an axis perpendicular to the plane of the Earth’s orbit around the Sun, there would be no variation in day lengths or temperatures throughout the year, and we would not have seasons. At Equinox, the midway between these two times in Spring and Autumn, the spin axis of the Earth points 90 degrees away from the Sun.

If your head is spinning from all of this, sit and ponder for a moment. Now is a great time to choose a marker and observe what’s happening for yourself. Trying a real science experiment for equinox is much better than the myth of balancing eggs. Just place a stake of some type into the ground (or use a fencepost or signpost) and periodically over the next few weeks measure the length of the shadow when the Sun is at its highest and write down your measurements. It won’t take long before your marker’s shadow length changes and you notice how the Sun’s position changes in the sky, and with it the ecliptic plane.

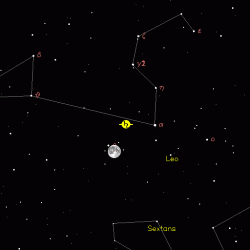

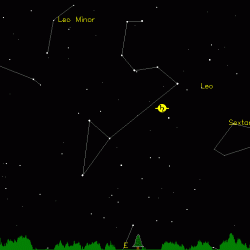

In the language of astronomy, an equinox is either of two points on the celestial sphere where the ecliptic and the celestial equator intersect. The Vernal Equinox is also known as “the first point of Aries” – a the point at which the Sun appears to cross the celestial equator from south to north. The equinoxes are not fixed points on the celestial sphere but move westward along the ecliptic, passing through all the constellations of the zodiac in 26,000 years. This is what’s known as the precession of the equinoxes – a motion first noted by Hipparchus roughly in 120 B.C. But what causes it?

The precession is caused the gravitational attraction of both the Moon and Sun on the equatorial bulge of the Earth. Imagine the Earth’s axis patterning itself in a cone as it moves, like a spinning top. As a result, the celestial equator, which lies in the plane of the Earth’s equator, moves on the celestial sphere, while the ecliptic, which lies in the plane of the Earth’s orbit around the Sun, is not affected by this motion. The equinoxes, which lie at the intersections of the celestial equator and the ecliptic, now move on the celestial sphere. Much the same, the celestial poles move in circles on the celestial sphere, so that there is a continual change in the star at or near one of these poles.

After a period of about 26,000 years the equinoxes and poles lie once again at nearly the same points on the celestial sphere. Because the gravitational effects of the Sun and Moon aren’t always the same, there is some wobble in the motion of the Earth’s axis called nutation. This wobble causes the celestial poles to move, not in perfect circles, but in a series of S-shaped curves with a period of 18.6 years that was first explained by Isaac Newton in 1687.

Go ahead and balance eggs for fun… But believe in science!

P.S. The Bad Astronomer Phil Plait has a tutorial video on his website, teaching you how to stand an egg on end, any time of the year. Click here to watch it.