Welcome back to Constellation Friday! Today, in honor of our dear friend and contributor, Tammy Plotner, we examine the Caelum constellation. Enjoy!

In the 2nd century CE, Greek-Egyptian astronomer Claudius Ptolemaeus (aka. Ptolemy) compiled a list of the then-known 48 constellations. Until the development of modern astronomy, his treatise (known as the Almagest) would serve as the authoritative source on astronomy. This list has since come to be expanded to include the 88 constellations that are recognized by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) today.

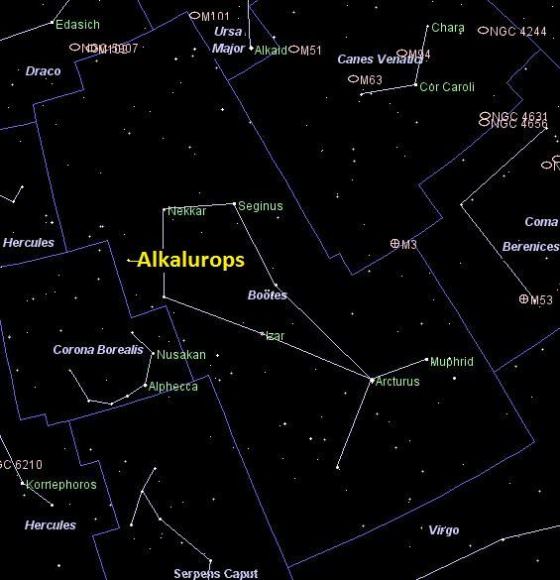

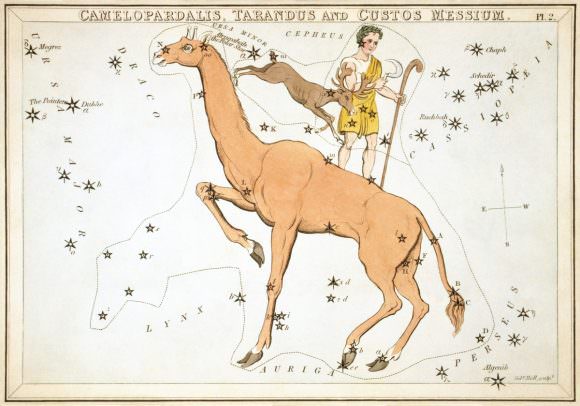

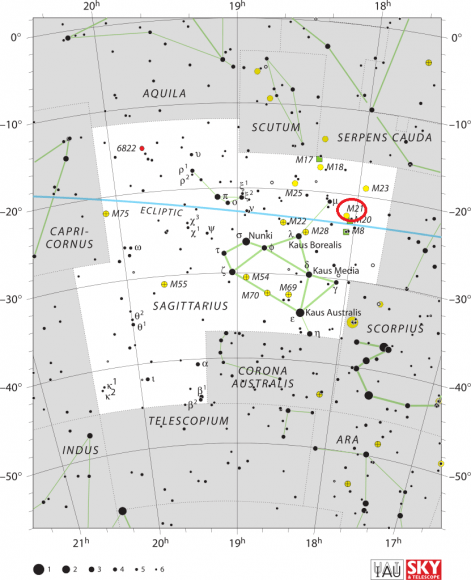

One of these modern additions is Camelopardalis, otherwise known as “the giraffe”. Located in the northern sky, this large but faint constellation is the eighteenth largest in the night sky. It belongs to the Ursa Major family of constellations and is bordered by Draco, Ursa Minor, Cepheus, Cassiopeia, Perseus, Auriga, Lynx, and Ursa Major and should be considered circumpolar.

Name and Meaning:

There is no real mythology connected to Camelopardalis since it is considered a “modern” constellation. Due to the faintness of the stars associated with it, the early Greeks considered this area of the sky to be empty – or a desert. But based on its Latin name, it could be considered to be a long-necked animal with the neck of a camel and the spots of a panther – connected to the twelve labors of Hercules.

The true nature of the “giraffe,” unfortunately, remains unclear. However, the name could be a reference to the book of Genesis in the Bible. a theory that is based on the fact that when Jacob Bartsch included Camelopardalis on his star map of 1624, he described the constellation as a camel on which Rebecca rode into Canaan. But since Camelopardalis represents a giraffe, not a camel, this explanation is not considered likely.

Notable Features:

Beta Camelopardalis is the brightest star in this constellation. It is a binary star with a yellow G-type supergiant as the primary and is located approximately 1,000 light years from Earth. Beta Cam is also an X-ray source, which suggests that it undergoes some kind of solar-like magnetic behavior (which accounts for its periodic flashes).

Camelopardalis’ second brightest star is CS Camelopardalis, another binary located approximately 3,000 light years away. It consists of a blue-white B-type supergiant that exhibits non-radial pulsations (which means that some portions of the star’s surface expand while others contract). It has a magnitude 8.7 companion located 2.9 arcseconds away, and the entire system is located in the reflection nebula vdB 14.

Then there’s Sigma 1694 Camelopardalis (aka. Struve 1694), which represents the “head’ of the giraffe. This binary star is composed of a white A-type subgiant located 300 light years from Earth, and a spectroscopic binary that consists of two A-type main sequence stars. Then there’s VZ Camelopardalis, a semi-regular variable M-type red giant located approximately 470 light years from Earth.

Camelopardalis is home to the asterism known as Kemble’s Cascade. Named after Father Lucian J. Kemble, a Franciscan Friar who discovered it, this asterism is formed by more than 20 stars that vary between magnitude 5 and 10 and form a straight line in the sky. After describing it to Walter Scott Houston (of Sky and Telescope magazine), Houston named it after Father Kemble and included it in his “Deep Sky Wonders” column in 1980.

Since Camelopardalis faces away from the galactic plane, a number of Deep Sky Objects are visible within its borders. These include NGC 2403, an intermediate spiral galaxy located approximately 12 million light years away. It was first discovered in the 18th century by William Herschel while he was working in England.

Then there’s NGC 1569, an irregular dwarf galaxy that is approximately 11 million light years away. This galaxy is known for the super star clusters it contains, both of which experience a considerable amount of star-forming activity. Then there’s NGC 1502, an open star cluster that is associated with Kemble’s Cascade and is located around 3,000 light years from Earth. NGC 1501, a planetary nebula, is located 1.4 degrees south of NGC 1502.

Camelopardalis is also home to IC 342, another intermediate spiral galaxy that is approximately 10.7 million light years away. It is one of the two brightest galaxies in the IC 342/Maffei Group (the nearest group of galaxies to the Local Group) and was discovered in 1895 by the British astronomer William Frederick Denning.

History of Observation:

Camelopardalis was first recorded by Jakob Bartsch in 1624 but was most likely created by Petrus Plancius in 1613. Camelopardalis is the eighteenth largest constellation in the night sky, and its brightest stars are of the fourth magnitude. It was German astronomer Johannes Hevelius who gave it the official name of “Camelopardus” (alternately “Camelopardalis”) because he saw the constellation’s many faint stars as the spots of a giraffe.

Some of the stars in this constellation were used by William Croswell to form the constellation Sciurus Volans in 1810. However, this did not catch on with later cartographers. Today, Camelopardalis is one of the 88 constellations used by the IAU.

Finding Camelopardalis:

Located Camelopardalis is not too difficult a task, given its proximity to several major constellations. However, it is quite faint compared to its immediate neighbors, so good viewing conditions (low light pollution) are a plus. One of the easiest ways is to locate the Big Dipper (Ursa Major) in the night sky, then tracing from the tip of the “spoon” directly outwards towards the head of the bear.

Next, locate Cassiopeia on the other side of the night sky – easily identified by its characteristic W shape. Camelopardalis is directly between them and is identifiable by the three stars (alpha, beta, gamma) that form the “neck” of the giraffe. For those who know its coordinates, it is located in the second quadrant of the northern hemisphere (NQ2) and can be seen at latitudes between +90° and -10°.

With 36 stars that have Bayer/Flamsteed designations, Camelopardalis provides many opportunities for star gazing. Using binoculars, Alpha Cam can be spotted. This rare, blue-white class O super giant may very well be a runaway star that originated from the associated cluster NGC 1502. It appears faint because it is dimmed by nearly a full magnitude by intervening interstellar dust, and its true luminosity might be as much as 530,000 times that of our Sun.

Now take a look at slightly brighter Beta. At 40 million years old and about 1000 light years from our solar system, Beta has a mass of about 7 times greater than our Sun. But lying just over an arc minute away is a companion star which is in itself a double star that takes at least a million years to orbit the super giant parent star! According to Jim Kaler, Beta Cam is also a double mystery, one which is most likely making the transition from a hydrogen-fusing dwarf (of hot class B) to a larger helium-fusing red giant.

Whatever its status, it falls into a zone of temperature and luminosity in which stars become unstable and pulsate as Cepheid variable stars. Beta Cam, however, does not vary, though some multiple pulsations are present with periods of tens of days. During aircraft observations of meteors in 1967, Beta Cam was seen suddenly to flash, brightening by about a full magnitude over the course of a quarter of a second. So keep your eye on it… If you can find it!

For larger binoculars and small telescopes, check out NGC 1502. This small open cluster of approximately 45 stars is made even better by its proximity to an asterism known as “Kemble’s Cascade”. To find it, simply look around Polaris in a counterclockwise rotation moving outward by a field twice. It is two full binocular fields from Alpha and Beta. The cluster itself is very attractive, but look closely in the telescope, and you will see it also contains two double stars – Struve 484 and Struve 485!

Larger binoculars and small telescopes will also have no problem picking up NGC 2403 from a dark sky location. NGC 2403 is a spiral galaxy discovered by William Herschel that belongs to the M81 galaxy group. At around 8 million light-years from Earth, larger telescopes will notice the northern spiral arm connects to NGC 2404 in a satellite galaxy interaction. Allan Sandage detected Cepheid variables in NGC 2403 using the Hale telescope, making it the first galaxy beyond our local group to have Cepheids found in it. As of late 2004, there had been two reported supernovae in the galaxy.

For larger telescopes and an observing challenge, try planetary nebula NGC 1501. Discovered in 1787 by Sir William Herschel and located about 4,890 light years away, this irregular disc has a great 14th magnitude central star hidden inside the dimpled structure, which gives rise to its popular moniker – the “Oyster Nebula.” Find the pearl!

For a dim fuzzy, hunt down NGC 2715. At magnitude 13.6, this small barred spiral galaxy may have recently experienced a galaxy merger, and as many as three supernovae events have been detected recently. For a true test of your observing skills and equipment, try IC 342. IC 342 is a nearby giant spiral that has a significant dust light extinction. It averages about magnitude 9, and it’s quite large (20′).

Once you’ve found it, see if you can spot its very stellar nucleus. While the exact size and mass of this galaxy are still the subject of controversy, there are strong indications that in many respects, IC 342 resembles a giant spiral (similar to our own Galaxy) and competes with two other near giant spirals – the Milky Way and Andromeda (M 31) – for the gravitational influence in the Local Volume.

There is one meteor shower associated with the constellation of Camelopardalis – the March Camelopardalids. They occur on or about March 22nd with no definite peak, and the fall rate averages only about one per hour. They are the slowest known meteors at 7 kps.

We have written many interesting articles about the constellation here at Universe Today. Here is What Are The Constellations?, What Is The Zodiac?, and Zodiac Signs And Their Dates.

Be sure to check out The Messier Catalog while you’re at it!

For more information, check out the IAUs list of Constellations.

Sources:

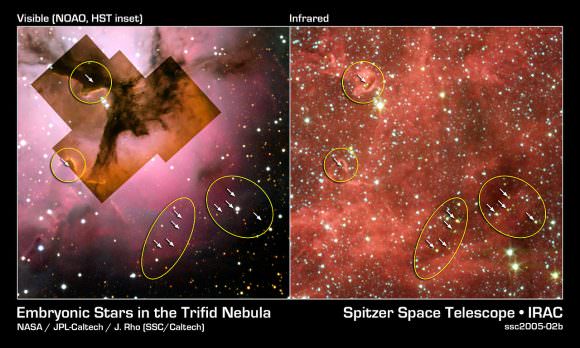

![The Trifid nebula (M20, NGC NGC 6514) in pseudocolor. Image taken with the Palomar 1.5-m telescope. The field of view is 16’ ´ 16’. Red shows [S II] ll 6717+6731. Green shows Ha l 6563. Blue shows [O III] l 5007. The WFPC2 field of view is indicated. Image: Jeff Hester (Arizona State University), Palomar telescope.](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/Trifid-Nebula-M20-e1469471610624-580x515.jpg)