Welcome back to Messier Monday! Today, in our ongoing tribute to Tammy Plotner, we take a look at the M15 globular cluster, one of the oldest and best known star clusters in the night sky. Enjoy!

In the 18th century, French astronomer Charles Messier began noticing a series of “nebulous objects” in the night sky while looking for comets. Not wanting other astronomers to make the same mistake, he began compiling a list of these objects into a catalog. In time, this list would include 100 objects, and came to be known by future astronomers as the Messier Catalog.

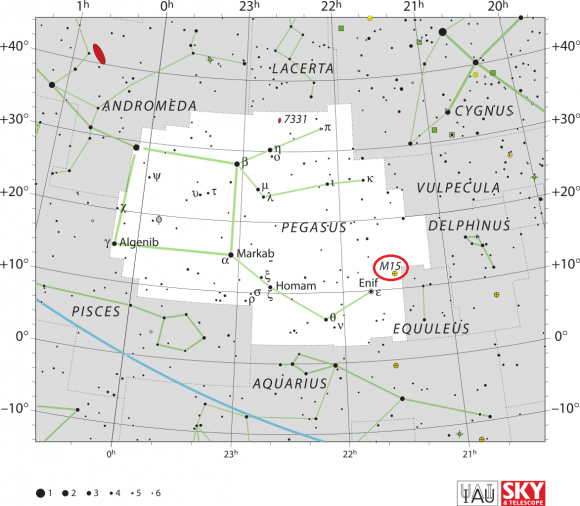

One of these objects is the globular cluster known as M15. Located in the northern constellation Pegasus, it is one of the brightest clusters in the night sky (with a visual brightness that is roughly 360,000 times that of our Sun). It is also one of the finest globular clusters in the northern section of the sky, the best deep-sky object in the constellation of Pegasus, and one of the oldest and best known globular clusters.

Description:

Messier 15 is probably the most dense globular cluster in our entire Milky Way galaxy – having already undergone a process of contraction. What does that mean to what you’re seeing? This ball of stars measures about 210 light years across, yet more than half of the stars you see are packed into the central area in a space just slightly more than ten light years in size.

By looking for single stars within globular clusters, the Hubble Space Telescope was either looking for a massive black hole or evidence of a “core collapse” – the intense gravity of so many stars so close together. Although it was peeking nearly 37,000 light-years away, the Hubble was able to resolve hundreds of stars converging on M15’s core. Like magnetism, their gravity would either cause them to attract or repel one another – and a black hole may have formed at some point in the cluster’s 12-billion-year life.

The study which addressed this data – which appeared in the January 1996 issue of the Astronomical Journal, was led by Puragra Guhathakurta of UCO/Lick Observatory, UC Santa Cruz – asked the question of whether or not the speed of the cluster’s stars could tell us if M15’s dense core was caused by a single huge object, or just mutual attraction. As Guhathakurta stated in the study:

“It is very likely that M15’s stars have concentrated because of their mutual gravity. The stars could be under the influence of one giant central object, although a black hole is not necessarily the best explanation for what we see. But if any globular cluster has a black hole at its center, M15 is the most likely candidate.”

John Bahcall and astrophysicist Jeremiah Ostriker of Princeton University were the first to forward the idea that Messier 15 might be hiding a black hole. While it is distinct from many other globular clusters by having such a dense core, it really isn’t that much different than all the rest of the globular clusters we see. Yet, no where else in our galaxy, except at its core, are the stars that dense!

It is estimated that 30,000 distinct stars exist in the inner 22 light-years of the cluster alone. The closer the Hubble telescope looked, the more stars it found. This increase in stellar density continued all the way to within 0.06 light-years of the center – about 100 times the distance between our Sun and Pluto. “Detecting separate stars that close to the core was at the limit of Hubble’s powers,” says Brian Yanny of the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory.

At this point, even the great Hubble could not distinguish individual stars, or locate the exact position of the core. Guhathakurta and is colleagues theorized that the stars crowd even closer inside the radius, so they plotted the distribution of the stars as a function of distance from the core. When the results came back, they had two answers – either a black hole was responsible, or a gravothermal catastrophe called core collapse was the culprit.

“It’s a catastrophe in the sense that once it starts, this process can run away very quickly,” said Guhathakurta. “But other processes could cause the core to bounce back before it collapses all the way.”

At an estimated 13.2 billion years old, it is one of the oldest known globular clusters, but it isn’t done throwing some surprises at us. M15 was the first globular cluster in which a planetary nebula, Pease 1 or K 648 (“K” for “Kuster”), could be identified – and can be seen with larger aperture amateur telescopes. Even stranger is the fact that Messier 15 contains 112 variable stars, and 9 known pulsars – neutron stars which are the leftovers of ancient supernovae. And one of these is a double neutron star system – M15 C.

History of Observation:

M15 was discovered by Jean-Dominique Maraldi on September 7, 1746 while he was looking for a comet. Says he:

“On September 7 I noticed between the stars Epsilon Pegasi and Beta Equulei, a fairly bright nebulous star, which is composed of many stars, of which I have determined the right ascension of 319d 27′ 6″, and its northern declination of 11d 2′ 22”. About 25 years later, Charles Messier would independently rediscover it to add to his own catalog, describing it as: “In the night of June 3 to 4, 1764, I have discovered a nebula between the head of Pegasus and that of Equuleus it is round, its diameter is about 3 minutes of arc, the center is brilliant, I have not distinguished any star; having examined it with a Gregorian telescope which magnifies 104 times, it had little elevated over the horizon, and maybe that observed at a greater elevation one can perceive stars.”

Sir William Herschel would be the first to resolve some of its stars, but not the core. It would be his son John who would later pick up structure. However, like the dutiful and colorful observer that he was, Admiral Smyth will leave us with this lasting impression:

“Although this noble cluster is rated as globular, it is not exactly round, and under the best circumstances is seen as in the diagram, with stragglers branching from a central blaze. Under a moderate magnifying power, there are many telescopic and several brightish stars in the field; but the accumulated mass is completely insulated, and forcibly strikes the senses as being almost infinitely beyond those apparent comets. Indeed, it may be said to appear evidently aggregated by mutual laws, and part of some stupendous and inscrutable scheme of involution; for there is nothing quiescent throughout the immensity of the vast creation.”

Considering Smyth’s observations were made nearly two centuries before we really began to understand what was going on inside Messier 15, you’ll have to admit he was a very good observer!

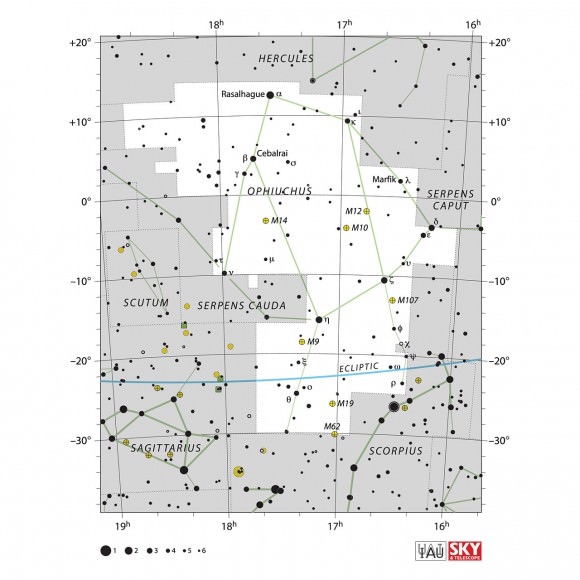

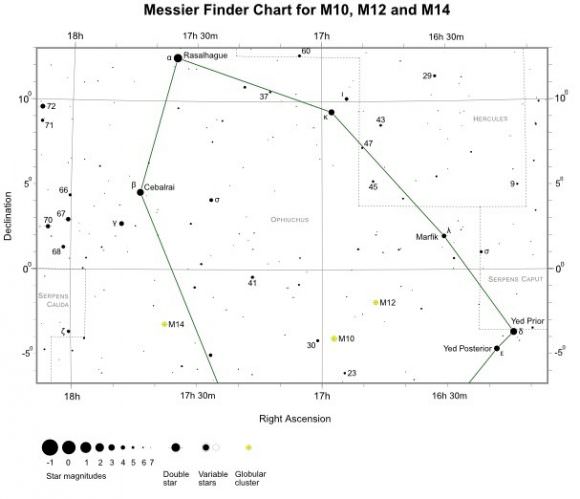

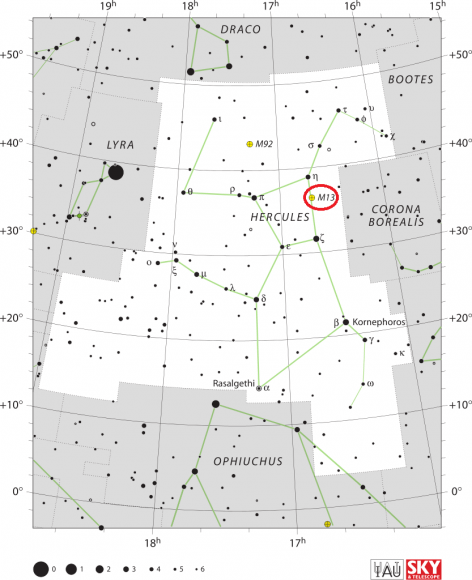

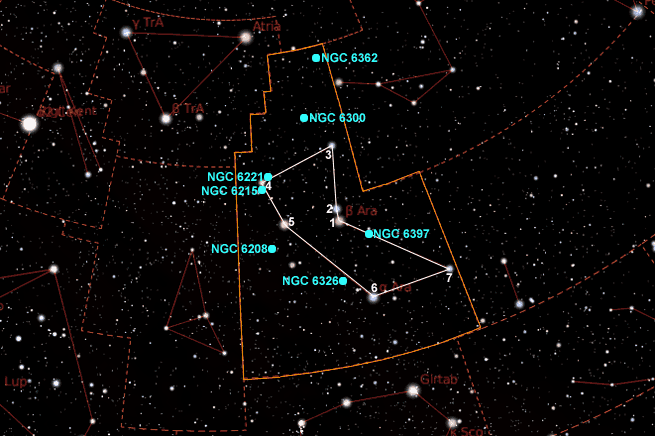

Locating Messier 15:

Surprisingly enough, globular cluster M15 is easy to find. Once you’ve located the “Great Square” of Pegasus, simply choose its brightest and southwesternmost star – Alpha. Now identify the small, kite shape of the constellation of Delphinus. Roughly halfway between these two (and slightly south), you’ll spy a slightly reddish star – Epsilon Peg (Enif).

By placing Enif in your binoculars or image correct finderscope at the 7:00 position, you can’t miss this bright, compact beauty. Even the smallest of optics will reveal the round glow and telescopes starting at 4″ will begin resolution – while large telescopes will simply amaze you. However, don’t expect to open this globular up to the core region. As already noted, its pretty dense in there!

And here are the quick facts for Messier 15, for your convenience:

Object Name: Messier 15

Alternative Designations: M15, NGC 7078

Object Type: Class IV Globular Cluster

Constellation: Pegasus

Right Ascension: 21 : 30.0 (h:m)

Declination: +12 : 10 (deg:m)

Distance: 33.6 (kly)

Visual Brightness: 6.2 (mag)

Apparent Dimension: 18.0 (arc min)

We have written many interesting articles about Messier Objects here at Universe Today. Here’s Tammy Plotner’s Introduction to the Messier Objects, , M1 – The Crab Nebula, M8 – The Lagoon Nebula, and David Dickison’s articles on the