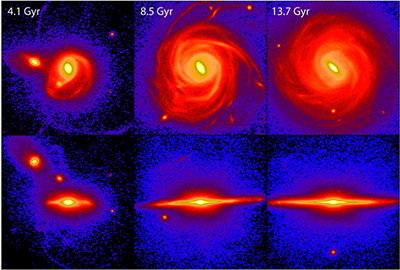

The Anglo-Australian Telescope in New South Wales has been watching how lazy giant galaxies gain size – and it isn’t because they create their own stars. In a research project known as the Galaxy And Mass Assembly (GAMA) survey, a group of Australian scientists led by Professor Simon Driver at the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR) have found the Universe’s most massive galaxies prefer “eating” their neighbors.

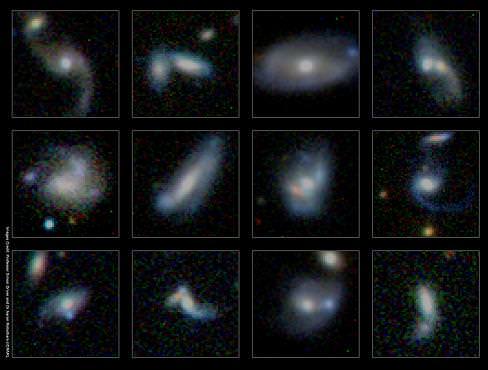

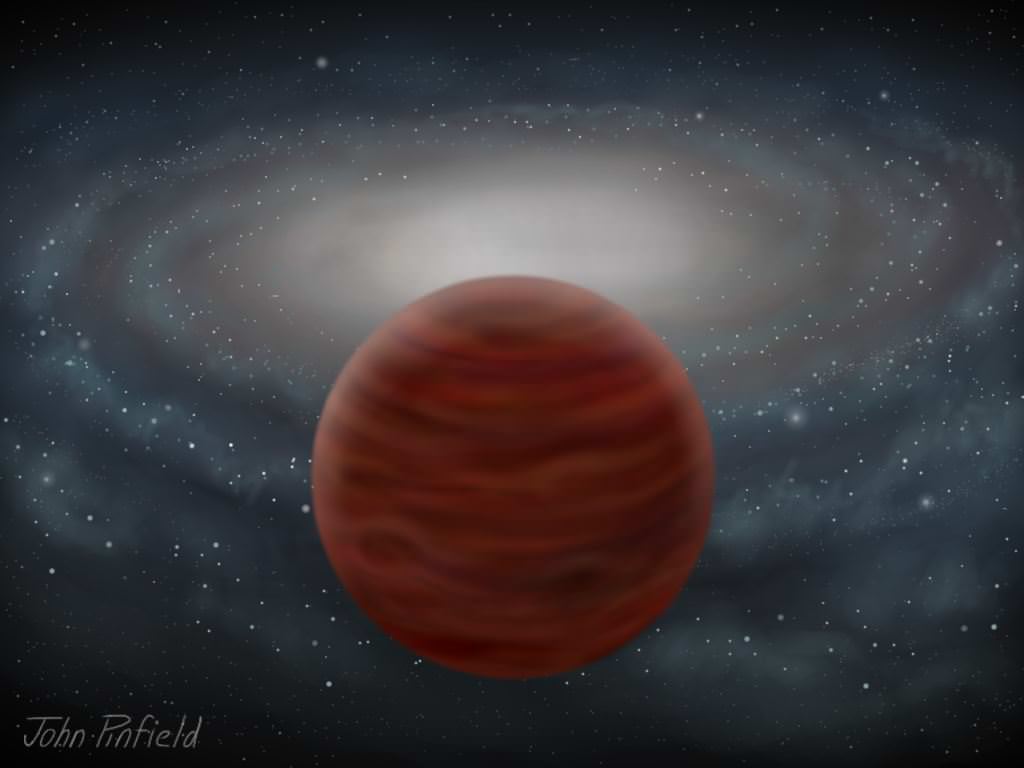

According to findings published in the journal “Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society”, astronomers studied more than 22,000 individual galaxies to see how they grew. Apparently smaller galaxies are exceptional star producers, forming their stellar members from their own gases. However, larger galaxies are lazy. They aren’t very good at stellar creation. These massive monsters rarely produce new stars on their own. So how do they grow? They cannibalize their companions. Dr. Aaron Robotham, who is based at the University of Western Australia node of the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR), explains that smaller ‘dwarf’ galaxies were being consumed by their heavyweight peers.

“All galaxies start off small and grow by collecting gas and quite efficiently turning it into stars,” he said. “Then every now and then they get completely cannibalized by some much larger galaxy.”

So how does our home galaxy stack up to these findings? Dr. Robotham, who led the research, said the Milky Way is at a tipping point and is expected to now grow mainly by eating smaller galaxies, rather than by collecting gas.

“The Milky Way hasn’t merged with another large galaxy for a long time but you can still see remnants of all the old galaxies we’ve cannibalized,” he said. “We’re also going to eat two nearby dwarf galaxies, the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, in about four billion years.” Robotham also added the Milky Way wouldn’t escape unscathed. Eventually, in about five billion years, we’ll encounter the nearby Andromeda Galaxy and the tables will be turned. “Technically, Andromeda will eat us because it’s the more massive one,” he said.

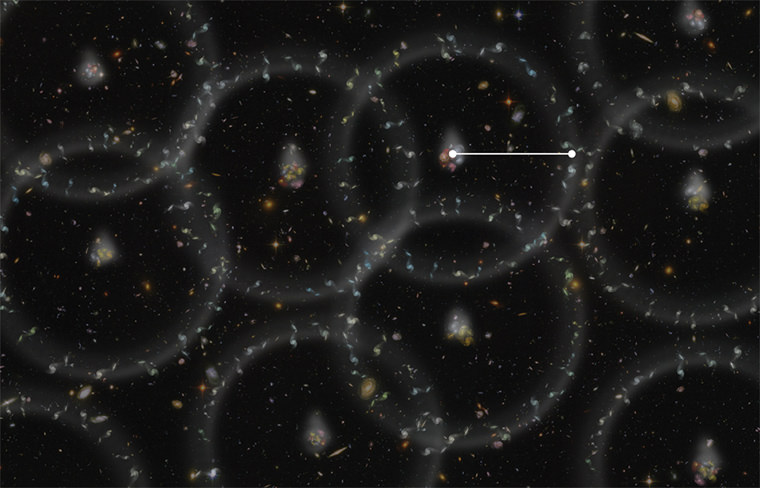

What exactly is going on here? Is it a case of mutual attraction? According to Dr. Robotham when galaxies grow, they acquire a heavy-duty gravitational field allowing them to suck in neighboring galaxies with ease. But why do they stop producing their own stars? Is it because they have exhausted their fuel? Robotham said star formation slow downs in really massive galaxies might be “because of extreme feedback events in a very bright region at the center of a galaxy known as an active galactic nucleus.”

“The topic is much debated, but a popular mechanism is where the active galactic nucleus basically cooks the gas and prevents it from cooling down to form stars,” Dr. Robotham said.

Will the entire Universe one day become just a single, large galaxy? In reality, gravity may very well cause galaxies groups and clusters to congeal into a limited number of super-giant galaxies, but that will take many billions of years to occur.

“If you waited a really, really, really long time that would eventually happen, but by really long I mean many times the age of the Universe so far,” Dr. Robotham said.

While the GAMA survey findings didn’t take billions of years, it didn’t happen overnight either. It took seven years and more than 90 scientists to complete – and it wasn’t a single revelation. From this work there have been over 60 publications and there are still another 180 in progress!

Original Story Souce: Monster galaxies gain weight by eating smaller neighbours – ICAR

Further reading: ‘Galaxy and Mass Assembly (GAMA): Galaxy close-pairs, mergers and the future fate of stellar mass’ in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. Published online 19/9/2014 at: http://mnras.oxfordjournals.org/lookup/doi/10.1093/mnras/stu1604 . Preprint version accessible at: http://arxiv.org/abs/1408.1476 .