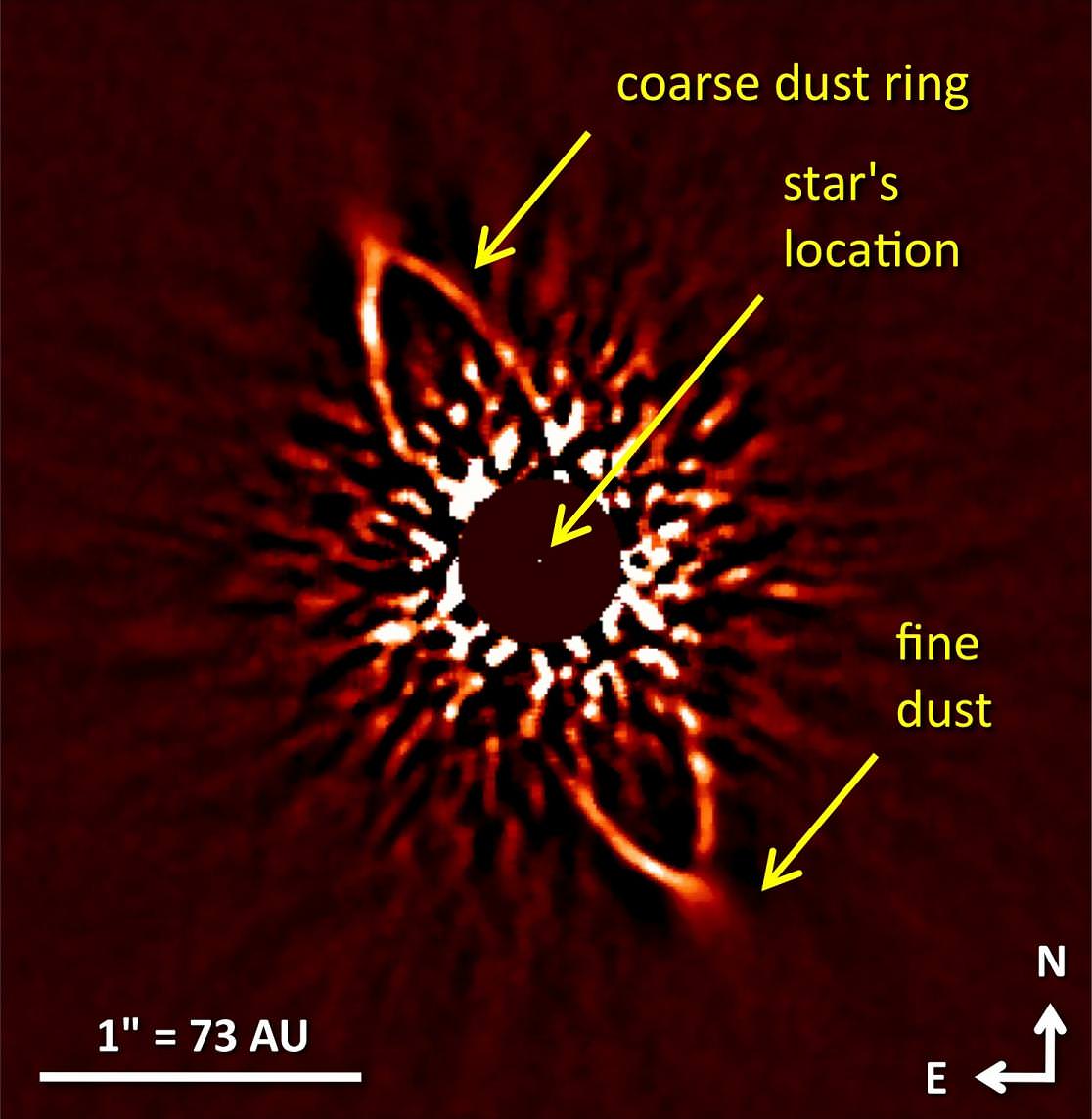

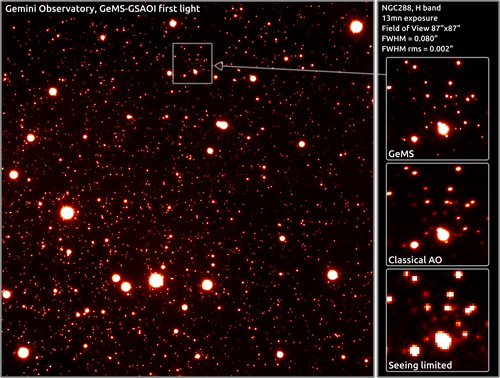

[/caption]When it comes to astrophotography, most of us would think that space-based telescopes like the Hubble are the epitome of imagining. However, there’s something new to be said about being “grounded”. On December 16, 2011, the Gemini South telescope in Chile revealed its first wide-field, ultra-sharp image… the product of a decade of hard work. By employing a new generation of adaptive optics (AO), the scope produced an incredible look into the densely concentrated globular cluster, NGC 288, and captured stars at close to the theoretical resolution limit of Gemini’s massive 8-meter mirror.

The Gemini Multi-conjugate adaptive optics System (GeMS for short), produced an incredible vision… one of incredible resolution. This new system will allow astronomers to study galactic centers and their black holes – as well as the life patterns of singular stars – with incredible clarity. It’s the largest amount of area ever captured in a single observation – one that’s ten times larger than any adaptive optics systems has ever been able to capture before. It has cause quite a stir in the astronomical community. When Space Telescope Science Institute director Matt Mountain saw the first light image, he praised the GeMS instrument team: “Incredible! You have truly revolutionized ground-based astronomy!”

As the director of the Gemini Observatory, Dr. Mountain was around when the project first began 10 years ago. He was responsible for assembling the team, including Francois Rigaut as the lead scientist to develop the GeMS instrument. And, Rigaut was there for first light… “We couldn’t believe our eyes!” Rigaut recalls. “The image of NGC 288 revealed thousands of pinpoint stars. Its resolution is Hubble-quality – and from the ground this is phenomenal.” Of course, one of the most amazing aspects of the image was how widely spaced the stars appeared, to which Rigaut comments: “This is somewhat uncharted territory: no one has ever made images so large with such a high angular resolution.”

Even though this is an incredible insight, some members of the scientific team which use the Gemini telescope are a bit more reserved in their comments. According to University of Toronto astronomer Roberto Abraham, one of a community of hundreds of astronomers worldwide who uses the 8-meter Gemini telescopes for cutting-edge research: “This is fan-freaking-tastic!!!!!!!” Exuberant? Of course! Even the environmental conditions remained as perfect as they could be for the first run of the GeMS equipment. “We were lucky to have clear weather and stable atmospheric conditions that night,” said Gemini AO scientist Benoit Neichel. “Even despite interruptions of the laser propagation due to satellites and planes passing by, we obtained our first image with the system. It was surprisingly crisp and large, with an exquisitely uniform image quality.”

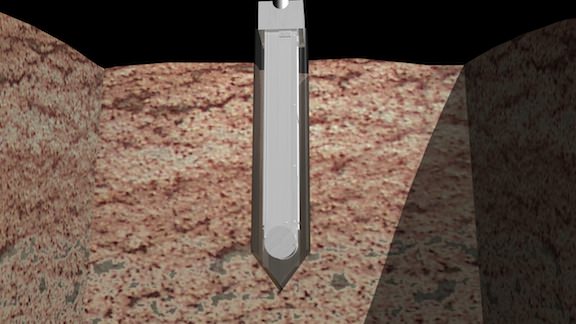

How is it accomplished? GeMS employs five laser guide stars, three deformable mirrors and a full arsenal of computers to provide a near diffraction limited image to the Gemini South Adaptive Optics Imager (GSAOI, built by the Australian National University) and the infrared-sensitive imager attached to it. This means the smallest detail that can be resolved measures about 0.04 to 0.06 arcsecond over a field of 85 arcseconds squared. Compared to 0.5 arcsecond “seeing limited” at a good viewing location, that’s phenomenal! Once resolution was solved, the next problem was extending the field of view through a technique called Multi-Conjugate Adaptive Optics (MCAO) – an endeavor which borrowed technology from other scientific fields, such as medical imaging.

“MCAO is game-changing,” Abraham said. “It’s going to propel Gemini to the next echelon of discovery space as well as lay a foundation for the next generation of extremely large telescopes. Gemini is going to be delivering amazing science while paving the way for the future.”

Original Story Source: Gemini Observatory News. For Further Reading: Gemini News Release.