[/caption]

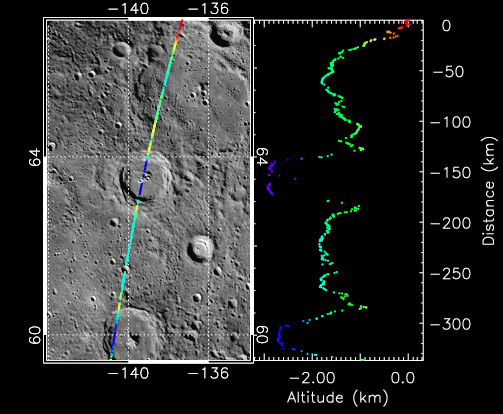

Getting to know a planet well is getting to know its surface features. Through measuring impact craters, planetary scientists are able to disclose information such as the origin and evolution of Mercury’s surface. We know it’s a matter of numbers, but just exactly how is it done when you can’t physically be there?

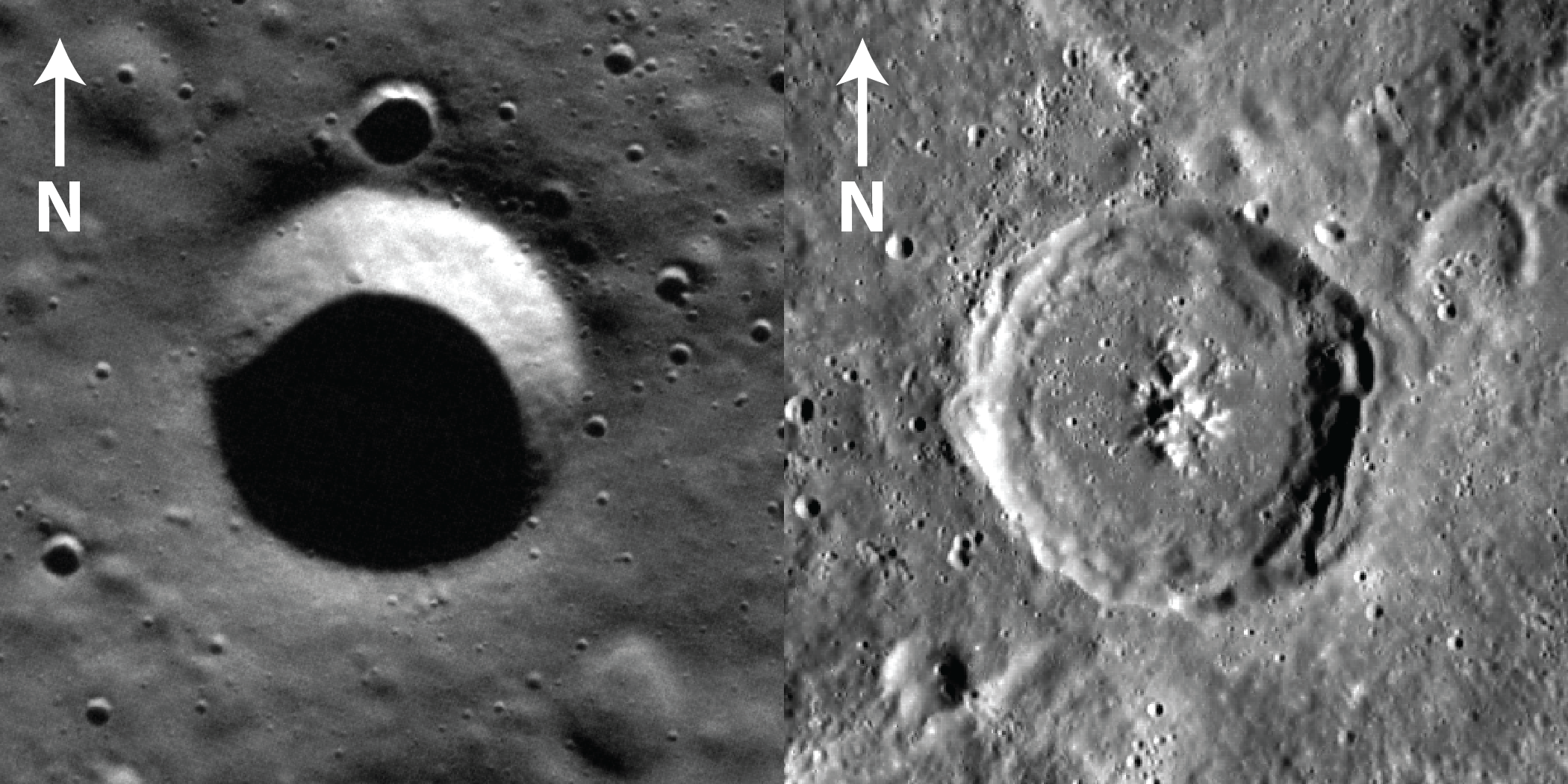

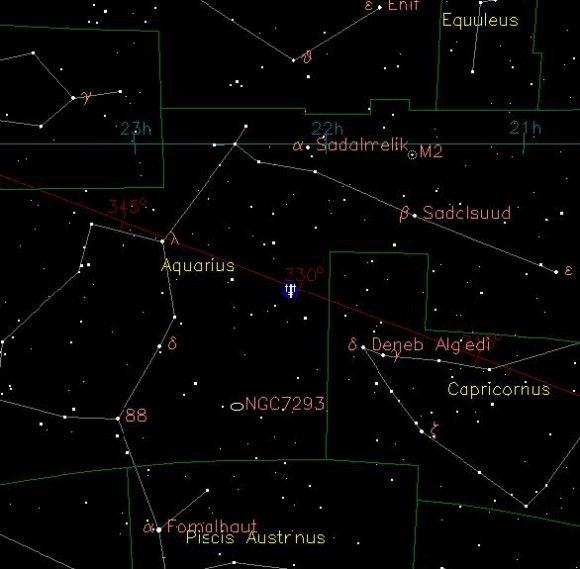

Size, shape and structure of craters is the common bond that most solar system bodies share. By understanding the physics of how they were made, researchers are able to draw conclusions through modeling. Their laboratory impact experiments and numerical simulations make judging crater qualities doable on a planetary scale. To further refine their results, it is then compared against known data for new, as well as eroded, craters. This information then gives us a clearer idea of surface properties, such as mineral deposits, soil composition, ice deposits, proportions and more. Checking out shapes and sizes on Mercury with observations obtained by the MESSENGER spacecraft are just the beginning.

Why is a Mercury crater investigation so important? Maybe because its surface gravitational acceleration (3.7 m/s2) is nearly identical to that at Mars. In this case, gravity plays an important role as the “transition diameter” is affected. According to the study, “Simple craters tend to be bowl shaped, whereas complex craters have terraced walls and can contain a central peak. If gravity were the dominant factor controlling the transition diameter, one would expect that this diameter would be similar on Mercury and Mars.” These transition diameters observed on Mercury are important because they give us clues to the Martian crust. Their differences could mean a weaker surface due to near-surface water ice.

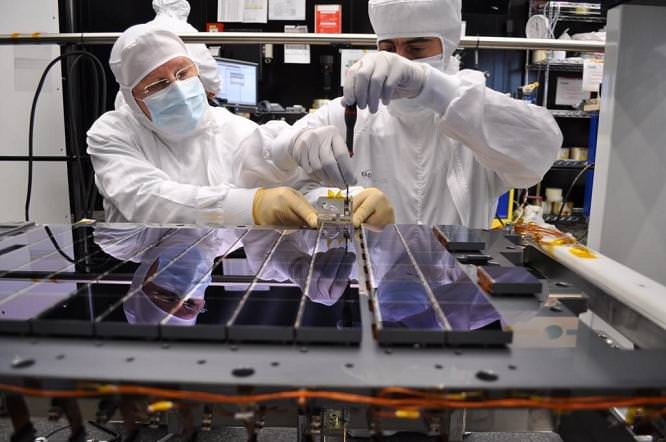

The Mercury Laser Altimeter (MLA) and the Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS) are hard at work providing the photo data needed to study cratering. We’re now able to get an inside look at central peaks, walls, floors and slopes. In addition, we’re getting a concise measurement of diameters. As with the Moon, researchers can make assessments as to depth by measuring the shadows. While MLA cannot always be used for these types of measurements, these fresh insights are furthering our understanding of crater properties – both on Mercury and across all holey bodies in our solar system.

Original News Source: Messenger News.