Welcome back to Messier Monday! In our ongoing tribute to the great Tammy Plotner, we take a look at globular cluster known as Messier 54!

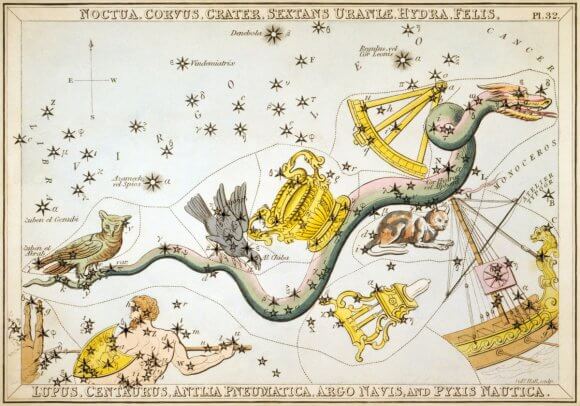

During the 18th century, famed French astronomer Charles Messier noted the presence of several “nebulous objects” in the night sky. Having originally mistaken them for comets, he began compiling a list of these objects so others would not make the same mistake he did. In time, this list (known as the Messier Catalog) would come to include 100 of the most fabulous objects in the night sky.

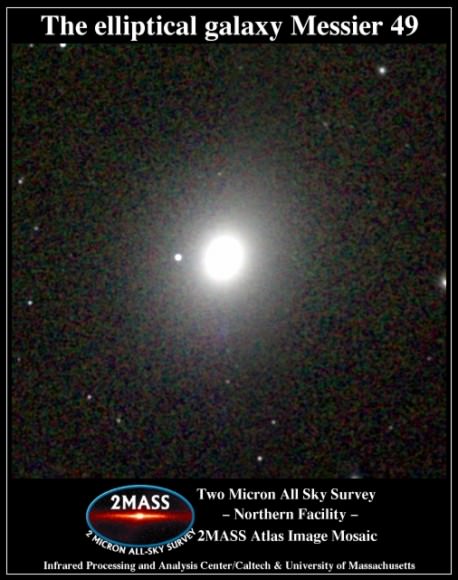

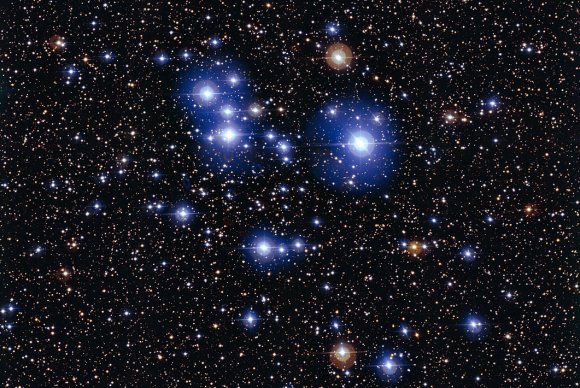

One of these objects is the globular cluster known as Messier 54. Located in the direction of the Sagittarius constellation, this cluster was once thought to be part of the Milky Way, located about 50,000 light years from Earth, In recent decades, astronomers have come to realize that it is actually part of the Sagittarius Dwarf Galaxy, located some 87,000 light-years away.

What You Are Looking At:

Running away from us at a speed of 142 kilometers per second, this compact globe of stars could be as wide as 150 light years in diameter and as far away as 87,400 light years. Wait… Hold the press… Almost 90 thousand light years? Yeah. Messier 54 isn’t part of our own Milky Way Galaxy!

In 1994 astronomers made a rather shocking discovery… this tough to resolve globular was actually part of the Sagittarius Dwarf Elliptical Galaxy. As Michael H. Siegal (et al) said in their study:

“As part of the ACS Survey of Galactic Globular Clusters, we present new Hubble Space Telescope photometry of the massive globular cluster M54 (NGC 6715) and the superposed core of the tidally disrupted Sagittarius (Sgr) dSph galaxy. Our deep (F606W ~ 26.5), high-precision photometry yields an unprecedentedly detailed color-magnitude diagram showing the extended blue horizontal branch and multiple main sequences of the M54+Sgr system. Multiple turnoffs indicate the presence of at least two intermediate-aged star formation epochs with 4 and 6 Gyr ages and [Fe/H]=-0.4 to -0.6. We also clearly show, for the first time, a prominent, ~2.3 Gyr old Sgr population of near-solar abundance. A trace population of even younger (~0.1-0.8 Gyr old), more metal-rich ([Fe/H]~0.6) stars is also indicated. The Sgr age-metallicity relation is consistent with a closed-box model and multiple (4-5) star formation bursts over the entire life of the satellite, including the time since Sgr began disrupting.”

Inside its compact depths lurk at least 82 known variable stars – 55 of which are the RR Lyrae type. But astronomers using the Hubble Space telescope have have also discovered there are two semi-regular red variables with periods of 77 and 101 days. Kevin Charles Schlaufman and Kenneth John Mighell of the National Optical Astronomy Observatory explained in their study:

“Most of our candidate variable stars are found on the PC1 images of the cluster center – a region where no variables have been reported by previous ground-based studies of variables in M54. These observations cannot be done from the ground, even with AO as there are far too many stars per resolution element in ground-based observations.”

But what other kinds of unusual stars could be discovered inside such distant cosmic stellar evolutionary laboratory? Try a phenomena known as blue hook stars! As Alfred Rosenberg (et al) said in their study:

“We present BV photometry centered on the globular cluster M54 (NGC 6715). The color-magnitude diagram clearly shows a blue horizontal branch extending anomalously beyond the zero-age horizontal-branch theoretical models. These kinds of horizontal-branch stars (also called “blue hook” stars), which go beyond the lower limit of the envelope mass of canonical horizontal-branch hot stars, have so far been known to exist in only a few globular clusters: NGC 2808, Omega Centauri (NGC 5139), NGC 6273, and NGC 6388. Those clusters, like M54, are among the most luminous in our Galaxy, indicating a possible correlation between the existence of these types of horizontal-branch stars and the total mass of the cluster. A gap in the observed horizontal branch of M54 around Teff = 27,000 K could be interpreted within the late helium flash theoretical scenario, which is a possible explanation for the origin of blue hook stars.”

But with the stars packaged together so tightly, even more has been bound to occur inside of Messier 54. As Tim Adams (et al) indicated in their study:

“We investigate a means of explaining the apparent paucity of red giant stars within post-core-collapse globular clusters. We propose that collisions between the red giants and binary systems can lead to the destruction of some proportion of the red giant population, by either knocking out the core of the red giant or by forming a common envelope system which will lead to the dissipation of the red giant envelope. Treating the red giant as two point masses, one for the core and another for the envelope (with an appropriate force law to take account of the distribution of mass), and the components of the binary system also treated as point masses, we utilize a four-body code to calculate the time-scales on which the collisions will occur. We then perform a series of smooth particle hydrodynamics runs to examine the details of mass transfer within the system. In addition, we show that collisions between single stars and red giants lead to the formation of a common envelope system which will destroy the red giant star. We find that low-velocity collision between binary systems and red giants can lead to the destruction of up to 13 per cent of the red giant population. This could help to explain the colour gradients observed in PCC globular clusters. We also find that there is the possibility that binary systems formed through both sorts of collision could eventually come into contact perhaps producing a population of cataclysmic variables.”

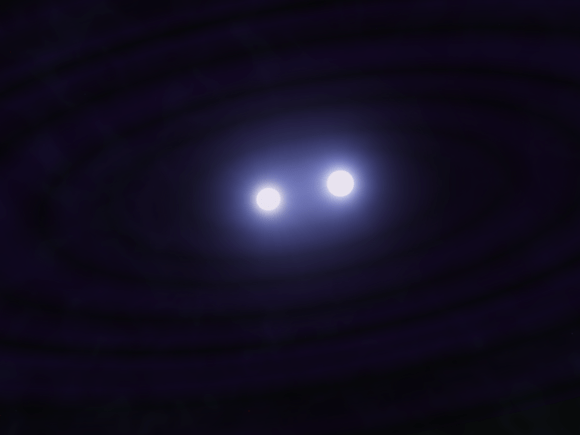

But the discoveries haven’t ended yet…. Because 2009 studies have revealed evidence for an intermediate mass black hole inside Messier 54 – the first known to have ever been discovered in a globular cluster.

“We report the detection of a stellar density cusp and a velocity dispersion increase in the center of the globular cluster M54, located at the center of the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy (Sgr). The central line-of-sight velocity dispersion is 20.2 ± 0.7 km s-1, decreasing to 16.4 ± 0.4 km s-1 at 2farcs5 (0.3 pc). Modeling the kinematics and surface density profiles as the sum of a King model and a point-mass yields a black hole mass of ~9400 M sun.” says R. Ibata (et al), “However, the observations can alternatively be explained if the cusp stars possess moderate radial anisotropy. A Jeans analysis of the Sgr nucleus reveals a strong tangential anisotropy, probably a relic from the formation of the system.”

History of Observation:

On July 24, 1778 when Charles Messier first laid eyes on this faint fuzzy, he had no clue that he was about to discover the very first extra-galactic globular cluster. In his notes he writes: “Very faint nebula, discovered in Sagittarius; its center is brilliant and it contains no star, seen with an achromatic telescope of 3.5 feet. Its position has been determined from Zeta Sagittarii, of 3rd magnitude.”

Years later Sir William Herschel would also study M54, and in his private notes he writes: “A round, resolvable nebula. Very bright in the middle and the brightness diminishing gradually, about 2 1/2′ or 3′ in diameter. 240 shews too pretty large stars in the faint part of the nebulosity, but I rather suppose them to have no connection with the nebula. I believe it to be no other than a miniature cluster of very compressed stars.”

Countless other observations would follow as the M54 became cataloged by other astronomers and each would in turn describe it only as having a much brighter core and some resolution around the edges. Have fun trying to crack this one!

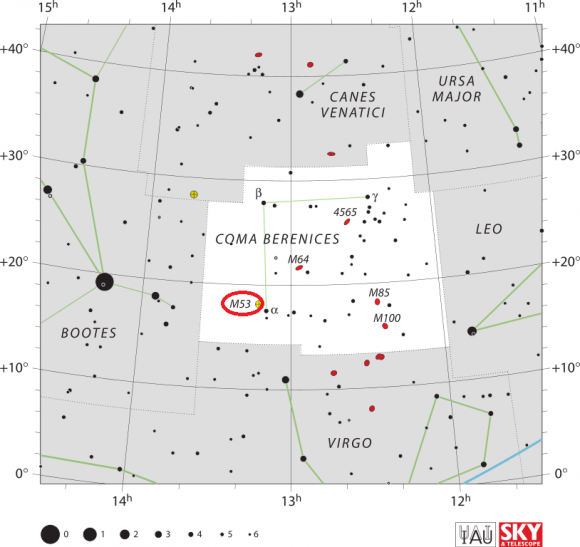

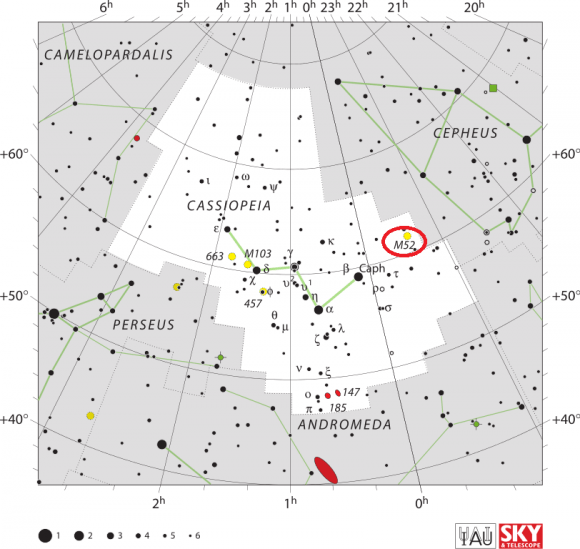

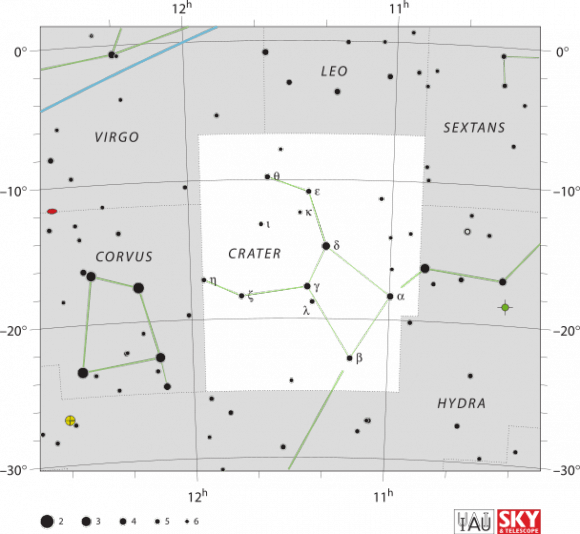

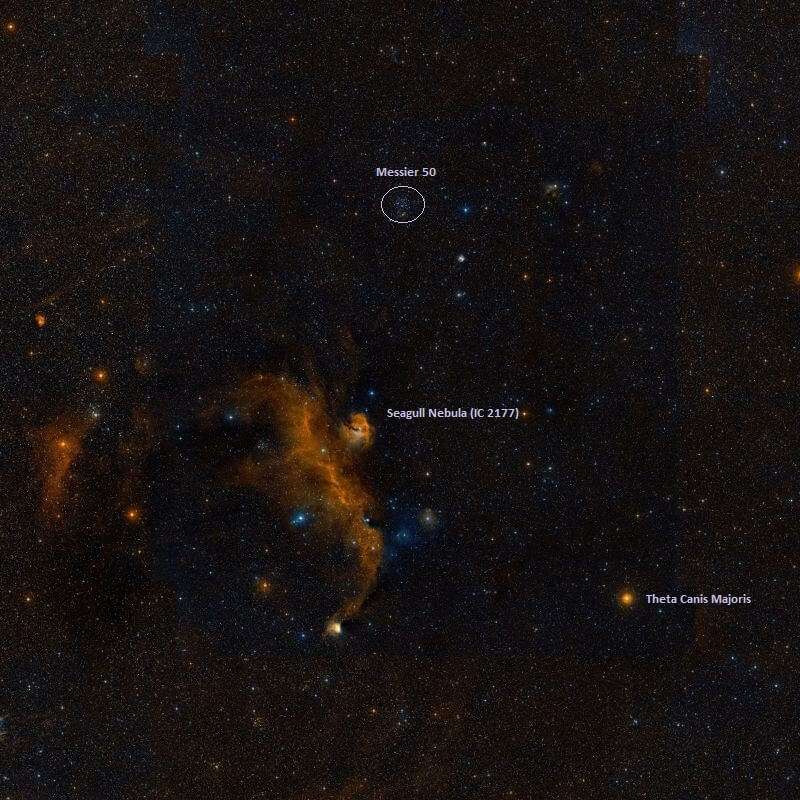

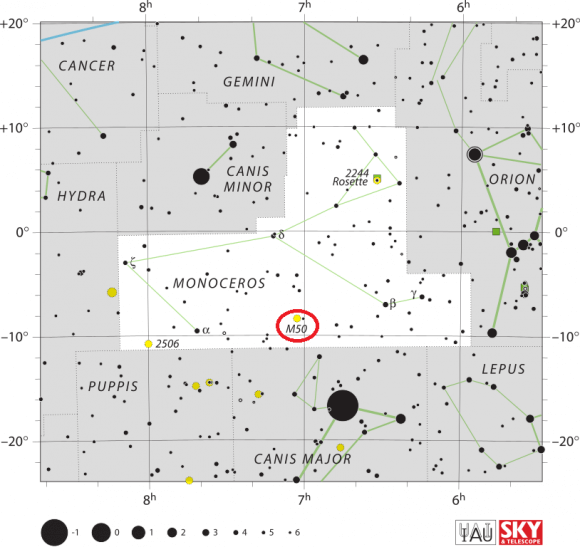

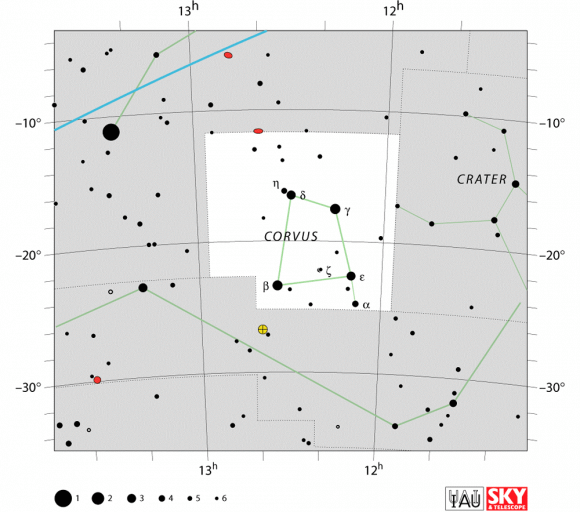

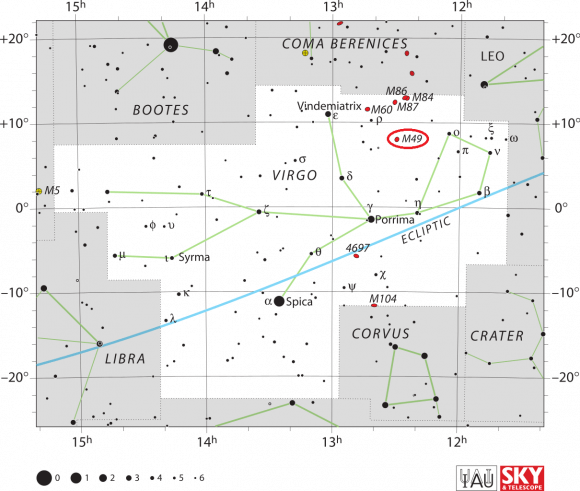

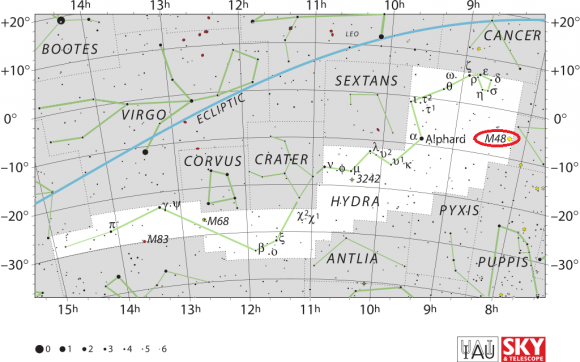

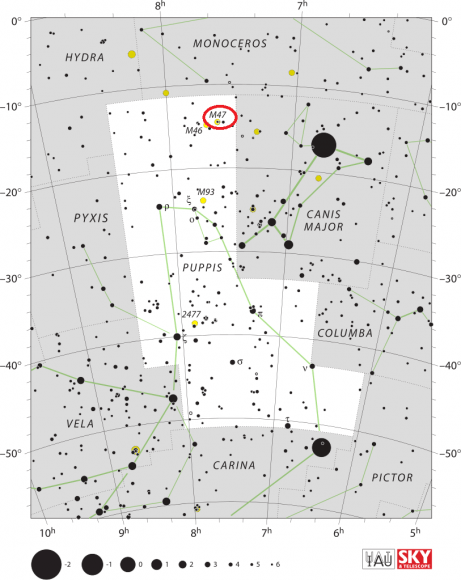

Locating Messier 54:

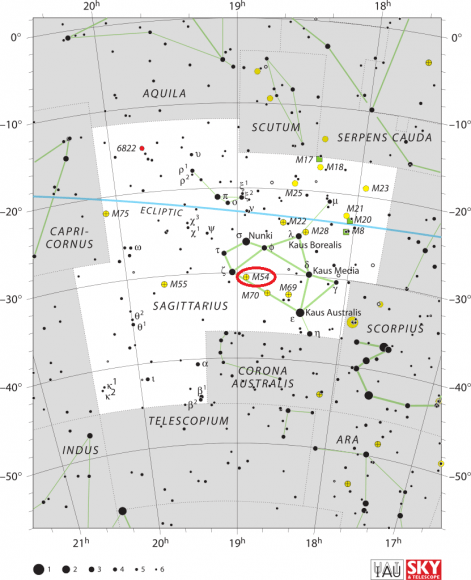

M54 isn’t hard to find… Just skip down to Zeta Sagittarii, the southwestern-most star of Sagittarius “teapot” and hop a half degree south and a finger width (1.5 degrees) west. The problem is seeing it! In small optics, such as binoculars or a finder scope, it will appear almost stellar because of its small size. However, if you just look for what appears like a larger, dim star that won’t quite come into perfect focus, then you’ve found it.

In smaller telescopes, you’ll get no resolution on this class III globular cluster because it is so dense. Large aperture doesn’t fare much better either, with only some individual stars making their appearance at the outer perimeters. Because of magnitude and size, Messier 54 is better suited to dark sky conditions.

And here are the quick facts on this Messier Object to help you get started:

Object Name: Messier 54

Alternative Designations: M54, NGC 6715

Object Type: Class III Extragalactic Globular Cluster

Constellation: Sagittarius

Right Ascension: 18 : 55.1 (h:m)

Declination: -30 : 29 (deg:m)

Distance: 87.4 (kly)

Visual Brightness: 7.6 (mag)

Apparent Dimension: 12.0 (arc min)

We have written many interesting articles about Messier Objects here at Universe Today. Here’s Tammy Plotner’s Introduction to the Messier Objects, , M1 – The Crab Nebula, M8 – The Lagoon Nebula, and David Dickison’s articles on the 2013 and 2014 Messier Marathons.

Be to sure to check out our complete Messier Catalog. And for more information, check out the SEDS Messier Database.

Sources: