Welcome to another edition of Constellation Friday! Today, in honor of the late and great Tammy Plotner, we take a look at the “Northern Crown” – the Corona Borealis constellation. Enjoy!

In the 2nd century CE, Greek-Egyptian astronomer Claudius Ptolemaeus (aka. Ptolemy) compiled a list of all the then-known 48 constellations. This treatise, known as the Almagest, would be used by medieval European and Islamic scholars for over a thousand years to come, effectively becoming astrological and astronomical canon until the early Modern Age.

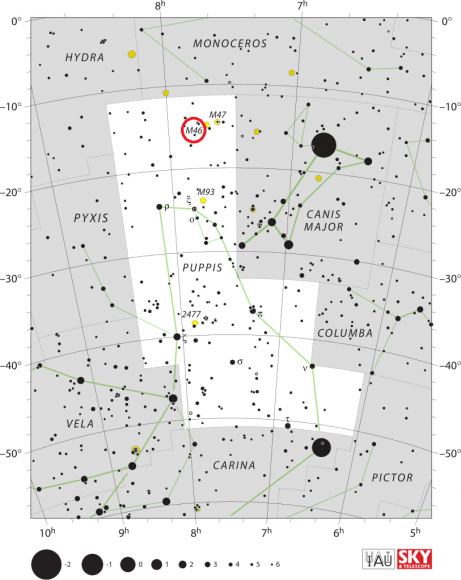

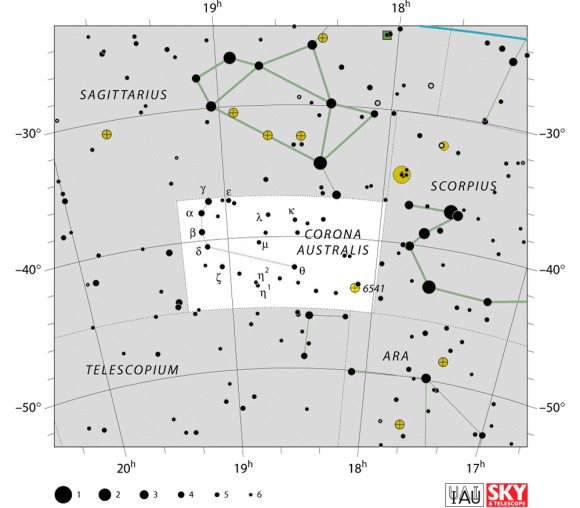

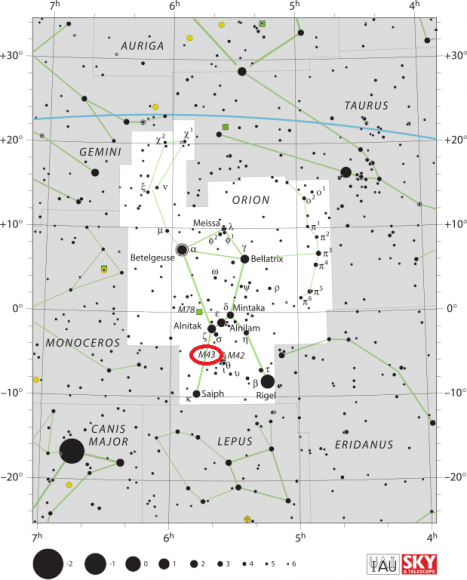

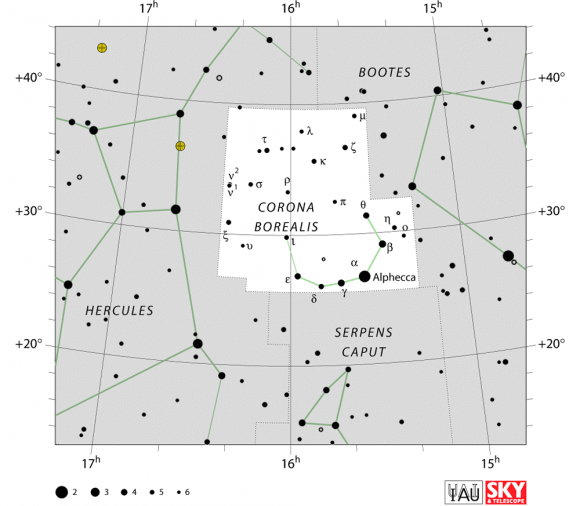

One of these constellations was Corona Borealis, otherwise known as the “Northern Crown”. This small, faint constellation is the counterpart to Corona Australis – aka. the “Southern Crown”. It is bordered by the constellations of Hercules, Boötes and Serpens Caput, and has gone on to become one of the 88 modern constellations recognized by the International Astronomical Union.

Name and Meaning:

In mythology, Corona Borealis was supposed to represent the crown worn by Ariadne – a present from Dionysus. In Celtic lore, it was known as Caer Arianrhod, or the “Castle of the Silver Circle”, home to the Lady Arianrhod. Oddly enough, it was also known to the Native Americans as well, who referred to it as the “Camp Circle” – a heavenly rendition of their celestial ancestors.

History of Observation:

Corona Borealis was one of the original 48 constellations mentioned in the Almagest by Ptolemy. To the medieval Arab astronomers, the constellation was known as al-Fakkah, which means “separated” or “broken up”– a reference to the resemblance of the constellation’s stars to a loose string of jewels (sometimes portrayed as a broken dish). The name was later Latinized as Alphecca, which was later given to Alpha Coronae Borealis. In 1920, it was adopted by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) as one of the 88 modern constellations.

Notable Objects:

Corona Borealis has no bright stars, 6 main stars and 24 stellar members with Bayer/Flamsteed designations. It’s brightest star – Alpha Coronae Borealis (Alphecca) – is an eclipsing binary located about 75 light years away. The primary components is a white main sequence star that is believed to have a large disc around it (as evidenced by the amount of infrared radiation it emits), and may even have a planetary or proto-planetary system.

The second brightest star, Beta Coronae Borealis (Nusakan), is a spectroscopic binary that is located 114 light years away. It is an Alpha-2 Canum Venaticorum (ACV) type star, a class of variable (named after a star in the constellation Canes Venatici) that are main sequence stars that are chemically peculiar and have strong magnetic fields. Its traditional name, Nusakan, comes from the Arabic an-nasaqan which means “the (two) series.”

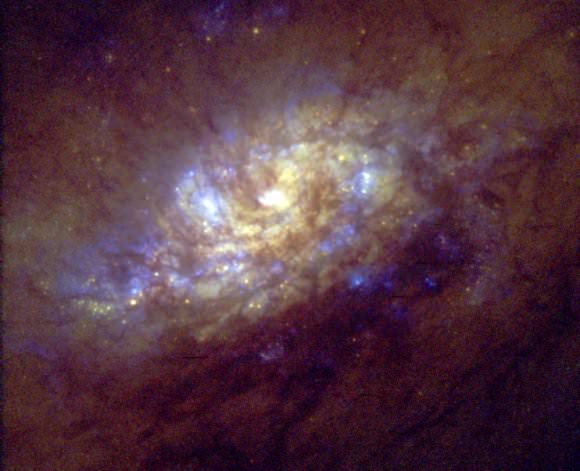

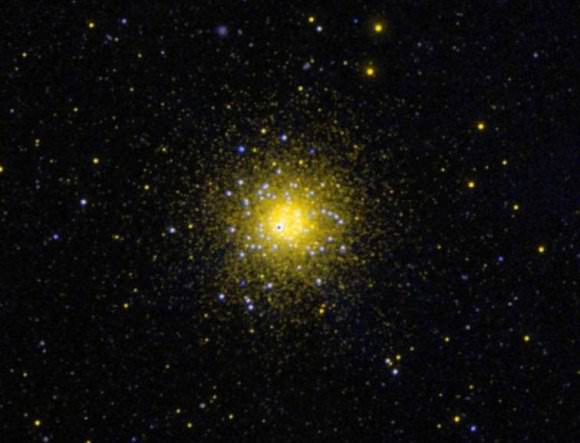

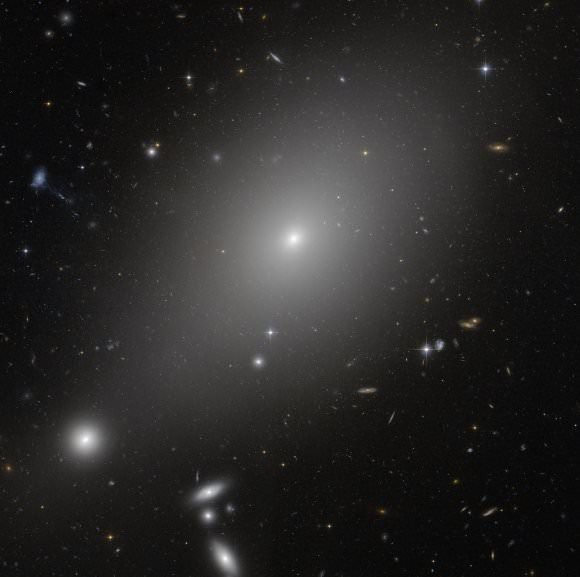

Corona Borealis contains few Deep Sky Objects that would be visible to amateur astronomers. The most notable is the Corona Borealis Galaxy Cluster (aka. Abell 2065), a densely-populated cluster located between 1 and 1.5 billion years from Earth. It lies about one degree southwest of Beta Coronae Borealis, in the southwest corner of the constellation. The cluster contains more than 400 galaxies in an area spanning about one degree in the sky.

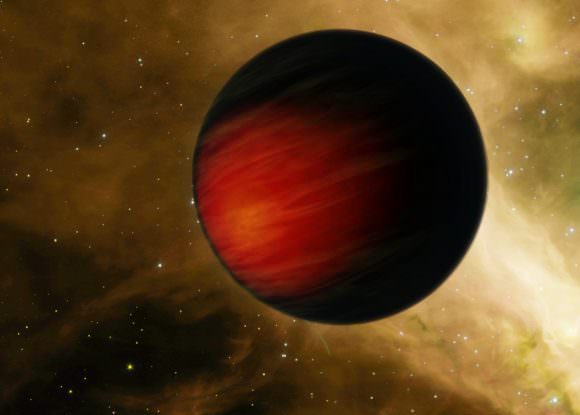

Corona Borealis also has five stars that have confirmed exoplanets orbiting them, most of which were detected using the radial velocity method. These include the the orange giant Epsilon Coronae Borealis, which has a Super-Jupiter (6.7 Jupiter masses) that orbits it at a distance of 1.3 AU and with a period of 418 days.

There’s also Kappa Coronae Borealis, an orange subgiant that is orbited by both a debris disk and a gas giant. This planet is 2.5 times as massive as Jupiter and orbits the star with a period of 3.4 years. Omicron Coronae Borealis is a clump giant (a type of red giant) with one confirmed exoplanet – a gas giant with 0.83 Jupiter masses that orbits its star every 187 days.

HD 145457 is an orange giant that has one confirmed planet of 2.9 Jupiter masses that takes 176 days to complete an orbit. XO-1 is a yellow main-sequence star located approximately 560 light-years away with a hot Jupiter (roughly the same size as Jupiter) exoplanet. This planet was discovered using the transit method and completes an orbit around its star every three days.

Finding Corona Borealis:

Corona Borealis is visible at latitudes between +90° and -50° and is best seen at culmination during the month of July. Using binoculars, let’s start with Alpha Coronae Borealis. It’s name is Gemma, or on some star charts – Alphecca. At 75 light years away, we have a nice binary star system whose companion star produces a very faint eclipse every 17.3599 days. Even though Gemma is quite some distance in relative sky terms from Ursa Major, you might be surprised to know that it’s actually part of the Ursa Major moving star group!

Shift your attention to Beta Coronae Borealis. It’s traditional name Nusakan. Again, it looks like one star, but it’s actually two. Nusakan is a double star that’s about 114 light-years and the primary is a variable star that changes every so slightly about every 41 days. The two components are separated by about 0.25 arc seconds – way too close for amateur telescopes – but that’s not all. In 1944 F.J. Neubauer found a small variation in the radial velocity of Nusakan which may lead to a third orbiting body about 10 times the size of Jupiter.

Now have a look at Gamma. Again, we have a binary star that’s just too darn close to split with anything but a large telescope. Struve 1967 is a close binary with an orbit of 91 years. The position angle is 265º and separation about 0.2″. Instead, try focusing your attention on Zeta 1 and Zeta 2. Known as Struve 1965, this pair is a pretty blue white and they are well spaced at 7.03″ and about one stellar magnitude in difference. Nu1 and Nu2 are also very pretty in binoculars. Here we have an optic double star. Although they aren’t physically related, this widely seperated pair of orange giant stars is a pleasing sight in binoculars!

Out of all the singular stars here, you definitely have to take a look at R Coronae Borelis – known as R Cor Bor. Discovered nearly 200 years ago by English amateur, Edward Pigot, R Coronae Borealis is the prototype star of the R Coronae Borealis (RCB) type variables. They are very unusual type of variable star – one where the variability is caused by the formation of a cloud of carbon dust in the line of sight. Near the stellar photosphere, a cloud is formed – dimming the star’s visual brightness by several magnitudes.

Then the cloud dissipates as it moves away from the star. All RCB types are hydrogen-poor, carbon- and helium-rich, and high-luminosity. They are simultaneously eruptive and pulsating. They could fade anywhere from 1 to 9 magnitudes in a month… Or in a hundred days. It’s normally magnitude 6… But it could be magnitude 14. No wonder it has the nickname “Fade-Out star,” or “Reverse Nova”!

Unfortunately, Corona Borealis contains no bright deep sky objects, but it does have one claim to fame – the highly concentrated galaxy cluster, Abell 2065. For observers with larger telescope, many members of this fascinating 1-1.5 billion light years distant group are visible. This rich cluster of galaxies is located slightly more than a degree southwest of Beta Cor Bor and covers about a full degree of sky! Not for the faint of heart… Some of these galaxies list at magnitude 18….

We have written many interesting articles about the constellation here at Universe Today. Here is What Are The Constellations?, What Is The Zodiac?, and Zodiac Signs And Their Dates.

Be sure to check out The Messier Catalog while you’re at it!

For more information, check out the IAUs list of Constellations, and the Students for the Exploration and Development of Space page on Canes Venatici and Constellation Families.

Sources: