[/caption]

About 13 million light-years away in the constellations Canes Venatici, there’s a cloud. No, it’s not the same clouds that most of us have been experiencing lately – but a cluster of galaxies which appear form a single large cloud-like structure. The one we’re focusing on is Canes Venatici I, just a small section of the Virgo Supercluster and just moving along with the expansion of the Universe. In it we see a galaxy that stands out from the crowd for a very good reason… it has very little or no dark matter. It’s name? Messier 94.

When the very gifted Pierre Mechain discovered this galaxy on March 22, 1781, it took two days before Charles Messier had the chance to confirm his observation and catalog it as object 94. From Messier’s notes: “`Nebula without star, above the Heart of Charles [alpha Canum Venaticorum], on the parallel of the star no. 8, of sixth magnitude of the Hunting Dogs [Canes Venatici], according to Flamsteed: In the center it is brilliant and the nebulosity [is] a bit diffuse. It resembles the nebula which is below Lepus, No. 79; but this one is more beautiful and brighter: M. Mechain has discovered this one on March 22, 1781. (diam. 2.5′)”.

While most observers and some reference guides refer to M94 as a barred spiral galaxy (Sb), the notable feature of all is a dual ring structure – evidence of a low-ionization nuclear emission-line region (LINER) galactic nucleus. The inner core is a starburst ring, where many stars form rapidly and undergo supernovae at an astonishing rate. These starbursts may also be accompanied by the formation of galactic jets as matter falls into the central black hole forming a resonance pattern. Says C. Munoz-Tunon: “The bulge and the inner bar drive disk gas motion, causing inward movements outside the H II ring and outward just inside, thereby accumulating material to trigger star formation on the ring. In the central part the bar drives the gas toward the center, which explains the substantial amount of gas in the nucleus in spite of the presence of a fossil starburst. The peculiar motions reported in the literature in reference to the ionized gas of the H II ring can be understood as infalling gas encountering the shock waves generated by the starburst knots on the H II ring and being raised above the galaxy disk. The scenario of star formation propagating from the nucleus outward used to explain the apparent expanding motion of the HI ring is not fully supported, in light of a comparison of the location of the HI ring with that of the FUV ring. The FUV ring peaks at about 45″-48″, which might point to an inward-propagating star formation scenario.”

But, the point is arguable. According to the work of John Kormendy and Robert Kennicutt, it’s possible that what we’re seeing is simply an illusion of starburst caused by our viewing angle. “The Universe is in transition. At early times, galactic evolution was dominated by hierarchical clustering and merging, processes that are violent and rapid. In the far future, evolution will mostly be secular the slow rearrangement of energy and mass that results from interactions involving collective phenomena such as bars, oval disks, spiral structure, and triaxial dark halos. Both processes are important now. This review discusses internal secular evolution, concentrating on one important consequence, the buildup of dense central components in disk galaxies that look like classical, merger-built bulges but that were made slowly out of disk gas. We call these pseudobulges.”

Regardless of what caused the dual ring structure and declining rotation curves – the true answer is still elusive. Oddly enough it was what was proposed in 2008 which made Messier 94 even more mysterious… the lack of dark matter.

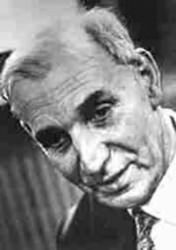

So, why should dark matter “matter”? That’s easy. We know its gravitational effects on visible matter and thereby we can explain the flat rotation curves of spiral galaxies, not to mention dark matter has a central role in galaxy structure formation and galaxy evolution. We owe these findings to Fritz Zwicky who told us that a a high mass-to-light ratio indicates the presence of dark matter in galaxies – just as he taught us that dark matter plays a role in galaxy clusters as well. Dr. Zwicky’s line of thinking was radical for the time… But is there still room for radical thinking? Why not?

According to the work of Joanna Jalocha, Lukasz Bratek and Marek Kutschera, ordinary luminous stars and gas account for all the material in M94 – with no room for dark matter. “The comparison of mass functions and rotation laws at the end of the previous section, illustrates the fact that the models with flattened mass distributions are more efficient than the commonly used models assuming spherical halo. The former are better in accounting both for high rotational velocities as well as for low scale structure of rotation curves and with noticeably less amount of matter than the latter (the relation between rotation and mass distribution in the disk model is very sensitive for gradients of a rotation curve). The use of the disk model is justified for galaxies with rotation curves violating the sphericity condition. This is necessary (although not sufficient) condition for a spherical mass distribution. Rotation of the spiral galaxy NGC 4736 can be fully understood in the framework of Newtonian physics. We have found a mass distribution in the galaxy that agrees perfectly with its high-resolution rotation curve, agrees with the I-band luminosity distribution giving low mass-to-light ratio of 1.2 in this band at total mass of 3.43 × 1010M, and is consistent with the amount of HI observed in the remote parts of the galaxy, leaving not much room (if any) for dark matter. Remarkably, we have achieved this consistency without invoking the hypothesis of a massive dark halo nor using modified gravities.

There exist a class of spiral galaxies, similar to NGC 4736, that are not dominated by spherical mass distribution at larger radii. Most importantly, in this region rotation curves should be reconstructed accurately in order not to overestimate the mass distribution. For a given rotation curve it can be easily determined whether or not a spherical halo may be allowed at large radii by examining the Keplerian mass function corresponding to the rotation curve (the so called sphericity test). By using complementary information of mass distribution, independent of rotation curve, we overcame the cutoff problem for the disk model, that for a given rotation curve, a mass distribution could not be found uniquely as it was dependent on the arbitrary extrapolation of the rotation curve.”

More explanation? Then step into MOND – Modified Newtonian dynamics where a modification of Newton’s Second Law of Dynamics (F = ma) is used to explain the galaxy rotation problem. It simply states that acceleration is not linearly proportional to force at low values. But will it work here? Who knows? Says Jacob Bekenstein: “The modified newtonian dynamics (MOND) paradigm of Milgrom can boast of a number of successful predictions regarding galactic dynamics; these are made without the assumption that dark matter plays a significant role. MOND requires gravitation to depart from Newtonian theory in the extragalactic regime where dynamical accelerations are small. So far relativistic gravitation theories proposed to underpin MOND have either clashed with the post-Newtonian tests of general relativity, or failed to provide significant gravitational lensing, or violated hallowed principles by exhibiting superluminal scalar waves or an {a priori} vector field.”

So next time you’re out observing galaxies, have a look at the “Cat’s Eye” Galaxy. Even a small telescope will reveal its bright, controversial nucleus and wispy shape. And thanks to outstanding astrophotographers like Roth Ritter we’re allowed to see a whole lot more…

Our thanks go to Roth Ritter of Northern Galactic for sharing his incredible work!