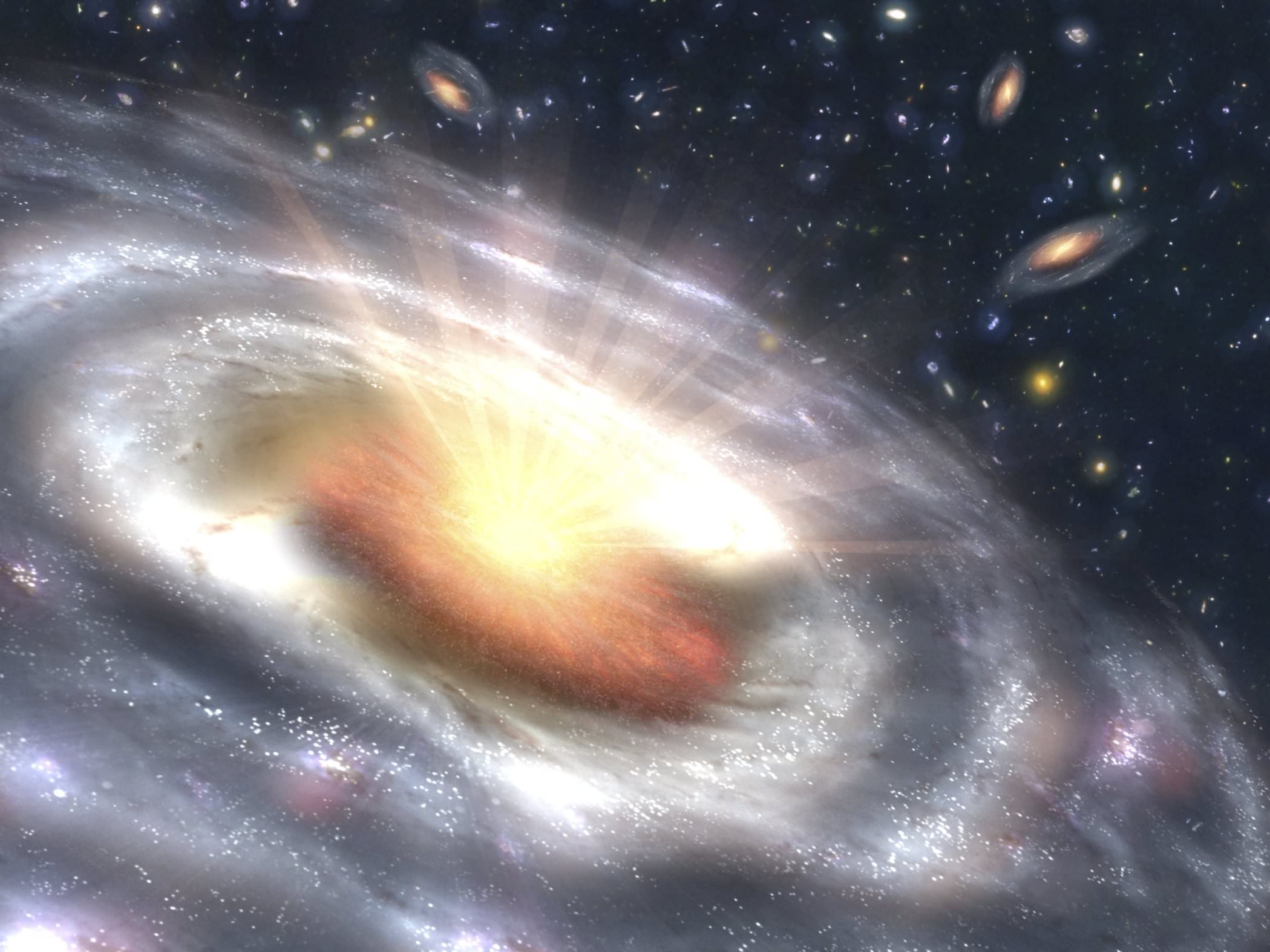

All the physical properties of our Universe – indeed, the fact that we even exist within a Universe that we can contemplate and explore – owe to events that occurred very early in its history. Cosmologists believe that our Universe looks the way it does thanks to a rapid period of inflation immediately before the Big Bang that smoothed fluctuations in the vacuum energy of space and flattened out the fabric of the cosmos itself.

According to current theories, however, interactions between the famed Higgs boson and the inflationary field should have caused the nascent Universe to collapse. Clearly, this didn’t happen. So what is going on? Scientists have worked out a new theory: It was gravity that (literally) held it all together.

The interaction between the curvature of spacetime (more commonly known as gravity) and the Higgs field has never been well understood. Resolving the apparent problem of our Universe’s stubborn existence, however, provides a good excuse to do some investigating. In a paper published this week in Physical Review Letters, researchers from the University of Copenhagen, the University of Helsinki, and Imperial College London show that even a small interaction between gravity and the Higgs would have been sufficient to stave off a collapse of the early cosmos.

The researchers modified the Higgs equations to include the effect of gravity generated by UV-scale energies. These corrections were found to stabilize the inflationary vacuum at all but a narrow range of energies, allowing expansion to continue and the Universe as we know it to exist… without the need for new physics beyond the Standard Model.

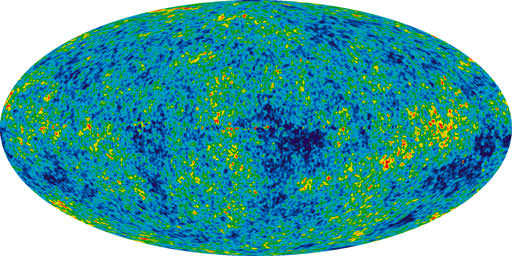

This new theory is based on the controversial evidence of inflation announced by BICEP2 earlier this summer, so its true applicability will depend on whether or not those results turn out to be real. Until then, the researchers are hoping to support their work with additional observational studies that seek out gravitational waves and more deeply examine the cosmic microwave background.

At this juncture, the Higgs-gravity interaction is not a testable hypothesis because the graviton (the particle that handles all of gravity’s interactions) itself has yet to be detected. Based purely on the mathematics, however, the new theory presents an elegant and efficient solution to the potential conundrum of why we exist at all.