[/caption]

Welcome back! Last time, we discussed the first few controversial and eventful moments following the birth of our cosmos. Looking around us today, we know that in the span of just a few billion years, the universe was transformed from that blistering amalgam of tiny elementary particles into a vast and organized expanse just teeming with large-scale structure. How does something like that happen?

Let’s recap. When we left off, the universe was a chaotic soup of simple matter and radiation. A photon couldn’t travel very far without bumping into and being absorbed by a charged particle, exciting it and later being emitted, just to go through the cycle again. After about three minutes, the ambient temperature had cooled to such an extent that these charged particles (protons and electrons) could begin to come together and form stable nuclei.

But, despite the falling temperature, it was still hot enough for these nuclei to start to combine into heavier elements. For the next few minutes, the universe cooked up various isotopes of hydrogen, helium and lithium nuclei in a process commonly known as big bang nucleosynthesis. As time went on and the universe expanded even further, these nuclei slowly captured surrounding electrons until neutral atoms dominated the landscape. Finally, after about 300,000 years, photons could travel freely across the universe without charged particles getting in their way. The cosmic microwave background radiation that astronomers observe today is actually the relic light from that very moment, stretched over time due to the expansion of the universe.

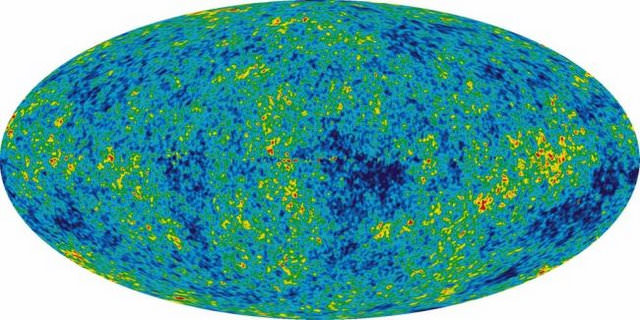

If you look at a picture of the CMB (above), you will see a pattern of differently colored patches that represent anisotropies in the background temperature of the cosmos. These temperature differences originally stemmed from tiny quantum fluctuations that were dramatically blown up in the very early universe. Over the next few hundred million years, the slightly overdense regions in the spacetime fabric attracted more and more matter (both baryonic – the kind that you and I are made of – and dark) under the influence of gravity. Some small regions eventually became so hot and dense that they were able to begin nuclear fusion in their cores; thus, in a delicate dance between external gravity and internal pressure, the first stars were born. Gravity then continued its pull, dragging clumps of stars into galaxies and later, clumps of galaxies into galaxy clusters. Some massive stars collapsed into black holes. Others grew so heavy and bloated that they exploded, spewing chunks of metal-rich debris in every direction. About 4.7 billion years ago, some of this material found its way into orbit around one unassuming main sequence star, creating planets of all sizes, shapes, and compositions – our Solar System!

Billions of years of geology and evolution later, here we are. And there the rest of the universe is. It’s a pretty striking story. But what’s next? And how do we know that all of this theory is even close to correct? Make sure to come back next time to find out!