As the International Space Station prepares to host its first one-year visit next year, it’s worth remembering that NASA didn’t just decide to send one of its astronauts into space that long suddenly. The decision to do that was built on years, nay, decades of experience of long-duration spaceflights and studies on how the human body changes, both in the American and Russian programs.

One of those more memorable excursions was NASA’s Skylab 4 in 1973-4, which Bill Pogue (reported dead yesterday at 84) took part in. In the mission’s 84 days — the longest manned excursion at the time — a lot happened. There was a dispute between ground control in the astronauts that some call a mutiny, but others disagree with. Also, the astronauts were tasked with observing a comet from orbit that was billed as the biggest one of the century, but showed up as a disappointing wash.

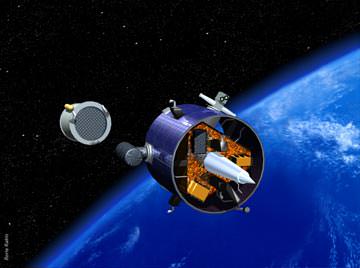

Although Skylab is not as well-known among the public today, it was NASA’s first space station and taught the agency a lot about working for the long run in space. In the moments after the station launched, a micrometeoroid shield intended to protect the station’s workshop tore away, exposing the station to harsh solar radiation. The first crew to arrive at Skylab in 1973 (called Skylab 2) had to do emergency fixes on the overheated station before they were able to use it.

Both Skylab 2 and 3 included veteran astronauts on its crews, but Skylab 4 was different. The three men launching to the station Nov. 16, 1973 were all space rookies (Jerry Carr, Ed Gibson, and Bill Pogue), although it should be noted they were sent after plenty of training on the ground and years of experience supporting other crews. Their mission, however, got off to a bad start.

“The crew … had problems during activation of the workshop that earlier crews had not faced,” reads a chapter of the NASA publication Skylab, Our First Space Station.

“One of its first tasks was to unload and stow within the spacecraft thousands of items needed for their lengthy manned period. The schedule for the activation sequence dictated lengthy work periods with a large variety of tasks to be performed. The crew soon found themselves tired and behind schedule. As the activation period progressed, the astronauts complained of being pushed too hard. Ground crews disagreed; they felt that the flight crew was not working long enough or hard enough.”

What happened next was what some termed a mutiny, and others a reasonable break in work task, as the astronauts took a day off. Another NASA publication, Lifting Aloft: Human Requirements for Extended Spaceflight, says the agency learned a valuable lesson about overprogramming astronauts on longer missions, but notes there were reports of the crew being hostile towards the ground nonetheless.

Once the crew members and ground control had a discussion about the situation, however, relations reportedly improved. And the crew did much before its Feb. 8, 1974 landing, exceeding its scheduled expectations. For example, they made observations of Comet Kohoutek, which was hyped by some publications such as Time as the “comet of the century” (a phrase that likely sounds familiar to bitter Comet ISON watchers of 2013.) The comet was not as bright as some observers hoped, but still bright enough from orbit for the crew to do visible and ultraviolet light observations.

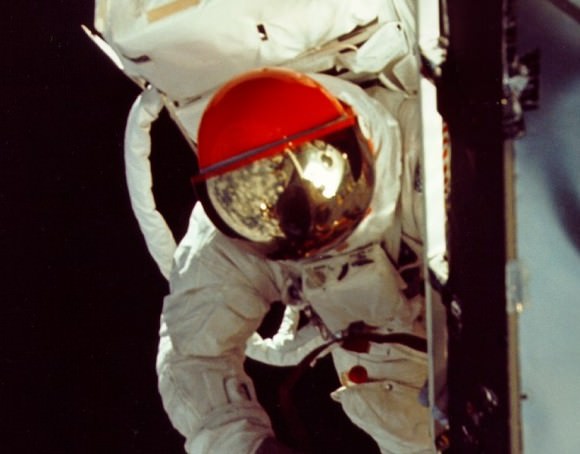

The crew also reported back on the value of exercise in orbit. International Space Station astronauts typically do two hours a day; the Skylab astronauts did several types for 1.5 hours. Equipment they used included a bicycle ergometer and a treadmill. They did long-term observations of the Earth and the Sun (at a time when there were few space-based observations of our closest star.) Pogue also performed two spacewalks, accumulating 13 hours and 31 minutes of experience “outside.”

Pogue, a veteran of the Korean war and past USAF Thunderbird member, had extensive experience in both American, British and Czech aircraft before being selected as one of a group of 19 astronauts in April 1966, just before the Apollo moon program started. He was a member of the astronaut support crews for Apollos 7, 11 and 14 and was supposed to head to the moon himself on Apollo 19 before that flight was cancelled. Pogue left NASA in 1977, four years before the shuttle program began, and worked as an aerospace consultant.