I’ll just leave this here.

Video by SG Collins/Postwar Media H/T to Gizmodo.

I’ll just leave this here.

Video by SG Collins/Postwar Media H/T to Gizmodo.

A small controversy has erupted over Neil Armstrong’s first words as he stepped on the Moon’s surface and how he came to say them.

Armstrong had always admitted that while he had been thinking about what to say during his first steps for quite some time before the Apollo 11 mission, he didn’t actually decide on his words until just after landing on the Moon, while waiting to exit the lunar module. In a new BBC documentary, the astronaut’s brother Dean Armstrong says the two discussed the statement months earlier, and that Neil gave Dean a handwritten note showing him the famous quote, “That’s one small step for (a) man, one giant leap for mankind.”

But apparently some people (and writers) have gotten a bit confused, thinking that Armstrong said he thought up the words on the spot, and recent headlines have screamed that “Armstrong Lied” about the quote.

Not so, says says space historian and author Andrew Chaikin, who wrote the book, “A Man on the Moon,” and interviewed Armstrong several times.

“I was distressed to see recent news stories claiming that Neil Armstrong lied to the world about when he made up his famous quote,” Chaikin said via email, and asked Universe Today to share the op-ed he wrote for Space.com.

In the op-ed piece, Chaikin cut to the chase, saying, “Let’s get one thing straight right now: Neil Armstrong was not a liar.” … “The problem, in some people’s minds, is that this seems to conflict with Neil’s own statements over the last 40 years about when and where he composed what became an immortal sentence when he took his first step onto the Moon,”

But it does not contradict history at all.

Chaikin notes that in Neil Armstrong’s first public statement about the famous quote at a post-flight press conference on Aug. 12, 1969, he said, “I did think about it. It was not extemporaneous, neither was it planned. It evolved during the conduct of the flight and I decided what the words would be while we were on the lunar surface just prior to leaving the LM.”

And when Chaikin interviewed Armstrong in 1988 for the book “A Man on the Moon,” Armstrong said the same thing, and he also told that to his biographer James Hansen in 2003.

“It is simply not true, as several recent news articles have claimed, that Armstrong always said he composed the quote ‘spontaneously,’” Chaikin wrote in the op-ed. “It would have been completely out of character for Armstrong, who was thoughtful about nearly everything he said and did, to have offered such an important quote without thinking it through beforehand.”

Chaikin says that Dean Armstrong’s story just adds a little ambiguity. “Maybe Neil had more than one quote in mind at that point, and only shared one of them with his brother. Or maybe the quote he showed his brother was an early draft, but after all these years, Dean remembers seeing the final version. We’ll probably never know the answer.”

But in no way does it mean that Armstrong “fibbed” or “lied” to the public for 40 years.

This isn’t the first time the famous first words have been a bit controversial. While the “a” in “one small step for a man” wasn’t audible in the broadcast to the world, Armstrong always said he did speak that word. A 2006 audio analysis of the broadcast supported Armstrong.

Neil Armstrong passed away in August 2012.

Image caption: Orion EFT-1 crew cabin construction ongoing inside the Structural Assembly Jig at the Operations and Checkout Building (O & C) at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC). This is the inaugural space-bound Orion vehicle due to blastoff from Florida in September 2014 atop a Delta 4 Heavy rocket. Credit: Ken Kremer

NASA is thrusting forward and making steady progress toward launch of the first space-bound Orion crew capsule -designed to carry astronauts to deep space. The agency aims for a Florida blastoff of the uncrewed Exploration Flight Test-1 mission (EFT-1) in September 2014 – some 20 months from now – NASA officials told Universe Today.

I recently toured the Orion spacecraft up close during an exclusive follow-up visit to check the work in progress inside the cavernous manufacturing assembly facility in the Operations and Checkout Building (O & C) at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC). Vehicle assemblage is run under the auspices of prime contractor Lockheed Martin Space Systems Corporation.

A lot of hardware built by contractors and subcontractors from all across the U.S. is now arriving at KSC and being integrated with the EFT-1 crew module (CM), said Jules Schneider, Orion Project manager for Lockheed Martin at KSC, during an interview with Universe Today beside the spacecraft at KSC.

“Everyone is very excited to be working on the Orion. We have a lot of work to do. It’s a marathon not a sprint to build and test the vehicle,” Schneider explained to me.

My last inspection of the Orion was at the official KSC unveiling ceremony on 2 July 2012 (see story here). The welded, bare bones olive green colored Orion shell had just arrived at KSC from NASA’s Michoud facility in New Orleans. Since then, Lockheed and United Space Alliance (USA) technicians have made significant progress outfitting the craft.

Workers were busily installing avionics, wiring, instrumentation and electrical components as the crew module was clamped in place inside the Structural Assembly Jig during my follow-up tour. The Jig has multiple degrees of freedom to move the capsule and ease assembly work.

“Since July and to the end of 2012 our primary focus is finishing the structural assembly of the crew module,” said Schneider.

“Simultaneously the service module structural assembly is also ongoing. That includes all the mechanical assembly inside and out on the primary structure and all the secondary structure including the bracketry. We are putting in the windows and gussets, installing the forward bay structure leading to the crew tunnel, and the aft end CM to SM mechanism components. We are also installing secondary structures like mounting brackets for subsystem components like avionics boxes and thruster pods as parts roll in here.”

Image caption: Window and bracket installation on the Orion EFT-1 crew module at KSC. Credit: Ken Kremer

“A major part of what we are doing right now is we are installing a lot of harnessing and test instrumentation including alot of strain gauges, accelerometers, thermocouples and other gauges to give us data, since that’s what this flight is all about – this is a test article for a test flight.

“There is a huge amount of electrical harnesses that have to be hooked up and installed and soldered to the different instruments. There is a lot of unique wiring for ground testing, flight testing and the harnesses that will be installed later along with the plumbing. We are still in a very early stage of assembly and it involves alot of very fine work,” Schneider elaborated. Ground test instrumentation and strain gauges are installed internally and externally to measure stress on the capsule.

Construction of the Orion service module is also moving along well inside the SM Assembly Jig at an adjacent work station. The SM engines will be mass simulators, not functional for the test flight.

Image caption: Orion EFT-1 crew cabin and full scale mural showing Orion Crew Module atop Servivce Module inside the O & C Building at the Kennedy Space Center, Florida. Credit: Ken Kremer

The European Space Agency (ESA) has been assigned the task of building the fully functional SM to be launched in 2017 on NASA’s new SLS rocket on a test flight to the moon and back.

Although Orion’s construction is proceeding apace, there was a significant issue during recent proof pressure testing at the O & C when the vehicle sustained three cracks in the aft bulkhead of the lower half of the Orion pressure vessel.

“The cracks did not penetrate the pressure vessel skin, and the structure was holding pressure after the anomaly occurred,” Brandi Dean, a NASA Public Affairs Officer told me. “The failure occurred at 21.6 psi. Full proof is 23.7 psi.”

“A team composed of Lockheed Martin and NASA engineers have removed the components that sustained the cracks and are developing options for repair work. Portions of the cracked surface were removed and evaluated, letting the team eliminate problems such as material contamination, manufacturing issues and preexisting defects from the fault tree. The cracks are in three adjacent, radial ribs of this integrally machined, aluminum bulkhead,” Dean stated.

Image caption: NASA graphic of 3 cracks discovered during recent proof pressure testing. Credit: NASA

The repairs will be subjected to rigorous testing to confirm their efficacy as part of the previously scheduled EFT-1 test regimen.

A great deal of work is planned over the next few months including a parachute drop test just completed this week and more parachute tests in February 2013. The heat shield skin and its skeleton are being manufactured at a Lockheed facility in Denver, Colorado and shipped to KSC. They are due to be attached in January 2013 using a specialized tool.

“In March 2013, we’ll power up the crew module at Kennedy for the first time,” said Dean.

Orion will soar to space atop a mammoth Delta IV Heavy booster rocket from Launch Complex 37 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida. Construction and assembly of the triple barreled Delta IV Heavy is the pacing item upon which the launch date hinges, NASA officials informed me.

Following the forced retirement of NASA’s space shuttles, the United Launch Alliance Delta IV Heavy is now the most powerful booster in the US arsenal and heretofore has been used to launch classified military satellites. Other than a specialized payload fairing built for Orion, the rocket will be virtually identical to the one that boosted a super secret U.S. National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) spy satellite to orbit on June 29, 2012 (see my launch story here).

Orion will fly in an unmanned configuration during the EFT-1 test flight and orbit the Earth two times – reaching an altitude of 3,600 miles which is 15 times farther than the International Space Station’s orbital position. The primary objective is to test the performance of Orion’s heat shield at the high speeds and searing temperatures generated during a return from deep space like those last experienced in the 1970’s by the Apollo moon landing astronauts.

The EFT-1 flight is not the end of the road for this Orion capsule.

“Following the EFT-1 flight, the Orion capsule will be refurbished and reflown for the high altitude abort test, according to the current plan which could change depending on many factors including the budget,” explained Schneider.

“NASA will keep trying to do ‘cool’ stuff”, Bill Gerstenmaier, the NASA Associate Administrator for Human Space Flight, told me.

Stay tuned – Everything regarding human and robotic spaceflight depends on NASA’s precarious budget outlook !

Image caption: Orion EFT-1 crew cabin assemblage inside the Structural Assembly Jig at the Operations and Checkout Building (O & C) at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC); Jules Schneider, Orion Project Manager for Lockheed Martin and Ken Kremer. Credit: Ken Kremer

40 years ago on December 19, 1972, Apollo 17 splashed down on Earth, marking the end of the manned moon missions. The astronauts came back with a treasure trove of rocks collected in 22 hours of extra-vehicular activity on the lunar surface, including “orange” soil that ended up coming from an ancient volcano.

Twitter wasn’t around back then, but anyone tuning into several Twitter accounts recently week would have a chance to experience what it could it have been like. Using mission transcripts and historical accounts of Apollo 17, these folks took it upon themselves to tweet the Apollo 17 mission, moment by moment, as “live” as possible.

Universe Today caught up with two of the tweeters. This is an edited version of what they said about the experience.

Liz Suckow (@LizMSuckow), a NASA contract archivist who tweeted on her own time

Researching a mission is divided into two parts, prelaunch and flight. For prelaunch, I use whatever official NASA documents, histories, and relevant astronaut and mission controller autobiographies I can find.

From what I’ve seen on the missions I’ve tweeted, until Apollo, no prelaunch conversation was transcribed at all. For Apollo, the last hour or so before liftoff is on the mission transcript. So, I can schedule those tweets. But, prelaunch activities for the astronauts start as long as 10 hours before liftoff. So, I use whatever resources I can to find references to the time of important events, and the rest of the prelaunch scheduling is educated guesswork. Flight is easy.

I have been trying to tweet as if I was the Johnson Space Center public affairs officer during the particular mission. When I joined Twitter in November of 2010 and was looking for accounts to follow, I came across a dead feed from JSC, I can’t remember the account name, that tweeted what had happened during a shuttle mission in real time.

Apollo 17, the only lunar mission to launch at night. Image Credit: NASA/courtesy of nasaimages.org

I thought, “Wow, that’s cool! Somebody ought to do that for the historical missions.” The celebration of the 40th anniversary of Apollo was still a big deal at NASA at the time, and the next mission up was Apollo 14. I figured someone else at NASA would have the same idea, but it was never mentioned. So, I figured I would do it on my personal account, just to see if it could be done and if anybody else (even if it was only a few people) liked the idea.

I am definitely going to be doing another one. I think the next anniversary is either Gordon Cooper‘s Mercury flight in May 2013, or the first Skylab missions. Not quite sure how I want to handle Skylab yet, may throw that one open to followers for ideas. Why do I do it? I do it because it is fun. Sometimes, I get so mentally involved the mission I get excited for what’s coming next as I am scheduling the tweets (even though I know full well what’s going to happen).

Buck Calabro (@Apollo17History), space fan who live-Tweeted along with Thomas Rubatscher

I’m live tweeting because I’m interested in Apollo. It’s a life-long interest. I myself live Tweet mostly by actually typing the tweet into HootSuite.com or Twitter.com. I have collaborated with Thomas by creating a spreadsheet of candidate tweets that he can upload into HootSuite’s bulk uploader for time-delayed tweeting.

My tweets mostly center around the command module pilot, Ron Evans. He spent three days all by himself in the CM, doing photography, mapping and other experiments. Not exactly the same sort of fame that the moonwalkers got. It’s a different kind of grit. Imagine being Evans, as AMERICA goes around the limb of the moon, completely cut off from every human being in the universe. Nothing but some fans, pumps and procedure to keep you going.

I have no plans for leveraging the Tweets. I’ll probably do another one someday. It’s a lot of work. As far as resources, I prefer source material. I have copies of the original transcripts for ground-to-air communications. The Apollo Lunar Surface Journal is a treasure trove of images and transcripts for the lunar surface portion of the mission, and the Lunar and Planetary Institute has an extensive catalog of imagery by camera magazine (which can be found in the transcripts.) NASA has scanned vast quantities of Apollo-era documentation, and the experiment results are likewise mostly available in the public domain.

The launch of Apollo 17. Credit: NASA

It was the end of an era. At 12:33 a.m. (EST) on Dec. 7, 1972 the monstrous Saturn V rocket blasted off for the final Apollo mission to the Moon. It was a stunning sight, as it was the first nighttime liftoff of the Saturn V. Aboard the Apollo 17 spacecraft were astronauts Gene Cernan, Ron Evans and Jack Schmitt.

Below are a couple of images and videos from the mission, one video is an overview of the mission, and the other is one of my favorite scenes:

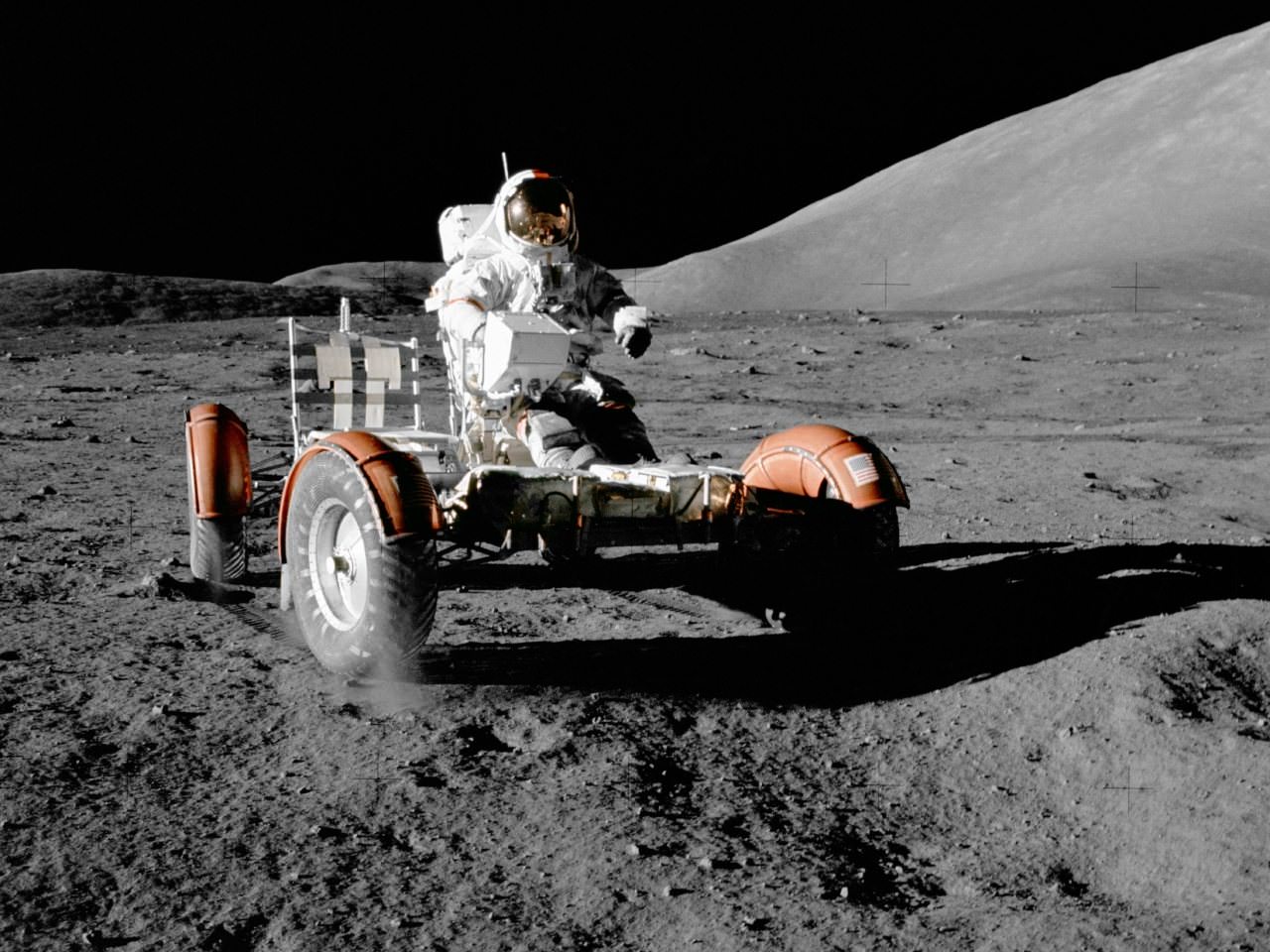

Gene Cernan driving the lunar rover during the Apollo 17 mission on the Moon. Credit: NASA

Jack Schmitt with the lunar rover at the edge of Shorty Crater. Credit: NASA

The famous “Blue Marble” image of Earth taken by the Apollo 17 crew on Dec. 7, 1972. Credit: NASA

On this day in history, on November 14, 1969, Apollo 12 successfully launched to the Moon. But it wasn’t without a little drama. The weather that day at Cape Canaveral in Florida was overcast with light rain and winds. However, at 11:22 am EST, the spacecraft, carrying astronauts Pete Conrad, Dick Gordon, and Alan Bean, blasted off into the clouds, in a seemingly perfect launch.

But thirty-seven seconds into launch, all hell broke loose.

“What the hell was that?” asked Gordon. Twenty seconds of confusion ensued, and then another disturbance occurred.

xkcd presents a Saturn V schematic using the 1,000 most used English words (xkcd.com)

Randall Munroe at xkcd did it again, this time with an illustration of a Saturn V described using only the 1,000 — er, ten hundred — words people use most often. The result is amusing, insightful and, as always, undeniably awesome.

Check out the Saturn-sized full frame comic below.

(And remember, if the end where the fire comes out of “starts pointing toward space you are having a bad problem and will not go to space today.”)

Source: xkcd.com.

The Kansas Cosmosphere and Space Center. (Elizabeth Howell)

Hutchinson, KS — While the nation is polarized between choosing Barack Obama or Mitt Romney as the next American president, voters going to the polls in this city of 40,000 will have another matter to weigh during elections today.

Along with their ballot, residents will consider whether the Kansas Cosmosphere and Space Center will continue to receive funding from city coffers. Since it represents 18% of revenues for the science museum, Cosmosphere president Jim Remar says his colleagues have been paying close attention.

The city sales tax sets aside 33% of a quarter-cent for the Cosmosphere, and some additional funding for a nearby underground salt museum and other city initiatives. Money to the museum goes for general operations.

“I feel good that it’s going to pass, although we do have some nervous moments,” Remar says. Supporters of the tax have been spreading the word through radio, billboards, editorials in local newspapers and any other means possible to get out the word.

Museum president Jim Remar, inside the Cosmosphere’s restoration facility. (Elizabeth Howell)

Sales tax funding for the Cosmosphere renews every five years, with the current iteration set to expire in 2014. The city tries to get the vote out for the sales tax at the same time as the general election, for convenience and financial sake.

While 18% of the museum’s funding lie in the hands of voters, Remar is trying to increase the share of the remaining 82% under the Cosmosphere’s control.

Getting visitors out to the museum is always a challenge; it’s an hour from the nearest major center (Wichita), a city that itself is many hours’ drive from any city to speak of. Still, the museum brings in 120,000 people every year, an attendance figure that includes space camps, museum visits and other events.

For the city itself, though, the museum is a jewel: “I can’t think of any other town of 40,000 that has such a facility,” says Remar, speaking proudly of how he grew up in the area, left and then chose to come back to help lead the museum’s management. His focus now is on trying to bring in business connections to enhance the Cosmosphere’s power in the community.

One of the most promising aspects is the Cosmosphere’s restoration and fabrication facility. The museum is perhaps most famous for putting the pieces of the Apollo 13 Odyssey spacecraft back together around the same time the movie came out in 1995. This was no easy task, as Odyssey was disassembled and scattered during an investigation into a near-fatal explosion aboard the spacecraft in 1970.

The restored control panel in Apollo 13’s Odyssey spacecraft, which sits in the Cosmosphere. (Elizabeth Howell)

The Cosmosphere required the Smithsonian’s help as the museum hunted through NASA centers, contract facilities and other spots for months in search of missing pieces. More than 85% of the spacecraft, which is on display at the Cosmosphere, was retrieved. The rest of the components came from spares and other odd pieces the Cosmosphere could find.

Restoration capabilities came out of necessity, Remar says. In the mid-1980s, the museum had a need to put spacecraft on display and spiffy them up for visitors. As other museums had the same requirement, the Cosmosphere gradually built out capabilities in restoration.

“It’s not something where somebody can come in a day and do it. It is a lot of trial and error,” Remar says of the employees who work in the facility. The lead mechanic has been around for 14 years, though, and there are two other workers with him who have adapted well over the years.

Cosmosphere officials realized there are only so many spacecraft to restore, and added exhibitions, replication and fabrication to their capabilities. This positioned them well for a surge of Hollywood films and other productions in the 1990s, such as Apollo 13, HBO’s From the Earth to the Moon, a short-lived TV series in the ’90s called The Cape and (in the 2000s) the IMAX film Magnificent Desolation: Walking on the Moon 3D.

An individual project will cost anywhere from $10,000 to $2.5 million to build; overall revenues from this division are 15 to 20% of the museum’s coffers every year. And that could grow bigger very soon.

A tool box inside the Cosmosphere’s restoration facility. (Elizabeth Howell)

On Saturday, a “Science of Aliens” exhibit will open in Taipei at the National Taiwan Science Education Center. One major part is a UFO spacecraft – 19 feet wide by 7 feet tall – that the Cosmosphere built for the exhibit. It includes running lights and some alien-sounding noises.

Asia happens to be a hot economy these days compared with North America and Europe, where the Comosphere’s work historically went.

The Cosmosphere is in discussions with Taipei-based Universal Impression, a broker that negotiated the science museum work, to do more work in the future. Remar says he hopes the Cosmosphere’s presence there will serve as a calling card to other Asian clients.

“International work can explode here,” he says. “There’s a lot of potential.”

Dealing with those who think the Apollo Moon landings never happened can be frustrating. Most of us just throw up our hands in exasperation, but Italian amateur astronomer Roberto Beltramini came up with a better idea: create a full 360-degree 3-D panorama of images from Apollo 16 to show “the true depth of the views taken by astronauts Apollo,” he said. “What better proof? This was the motivation that prompted me to start, but the spectacle and the interest in new ways of seeing the [Moon’s] wilderness, made me go farther.”

This panorama has now been put into a “Zoomify” making it fully interactive and lots of fun to explore. Grab your 3-D glasses, and you can find a rock and zoom in, follow the astronauts’ footprints and see one of the astronauts tinkering with the Lunar Rover. Click here and enjoy!

Beltramini’s initial plan was to create just a few 3-D anaglyghs, but once he got started, he just kept going. But of course, the Apollo 16 images taken by astronauts John Young and Charlie Duke as they walked, bounded and drove the lunar rover on the Moon’s surface were not originally taken with the intent to be made into 3-D view, making Beltramini’s job fairly difficult.

“The difficulty of making anaglyph, due to the shots not performed specifically for the purpose, may have dampened the attempts of other enthusiasts,” he writes on the website for amateur astronomy group in Viareggio, in the Tuscany region of Italy (Gruppo Astronomico Viareggio.) “To overcome this obstacle, I had to work adapting the pairs of pictures with graphics programs, cropping, resizing, by cleaning scratches and stains present because of the scans on the original story. Other marks are very annoying problem, that is, the black crosses placed at regular intervals in photographs taken during the Apollo missions that I had to delete one by one to avoid that interfere with 3D viewing.”

But over time he figured out how to make it work, “thanks to the phenomenon of rotation around a nodal point during the panning of the Apollo missions is possible, if there is plenty of overlap of the images, create a 3D 360 degree panorama,” he told Universe Today.

Apollo 16 was the fourth mission to land on the moon and launched on July 26, 1971, and the astronauts returned to Earth on August 7. Find out more about Apollo 16 here.

Looking very similar to the iconic first footprint on the Moon from the Apollo 11 landing, this new raw image from the Curiosity rover on Mars shows one of the first “scuff” marks from the rover’s wheels on a small sandy ridge. This image was taken today by Curiosity’s right Navcam on Sol 57 (2012-10-03 19:08:27 UTC). Rover driver Matt Heverly described a scuff as spinning one wheel to move the soil below it out of the way.

Besides being on different worlds, the two prints likely have a very different future. NASA says the first footprints on the Moon will be there for a million years, since there is no wind to blow them away. Research on the tracks left by Spirit and Opportunity revealed the time scale for track erasure by wind is typically only one Martian year or two Earth years.

Here’s one of Buzz Aldrin’s bootprint, to compare:

The GRIN website (Great Images in NASA) says this is an image of Buzz Aldrin’s bootprint from the Apollo 11 mission. Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked on the Moon on July 20, 1969. Credit: NASA

Curiosity chief scientist John Grotzinger compared earlier images of some of the first tracks left on Mars by Curiosity to images of the footprints left by Aldrin and Armstrong on the Moon. “I think instead of a human, it’s a robot pretty much doing the same thing,” he said.

Lead Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech