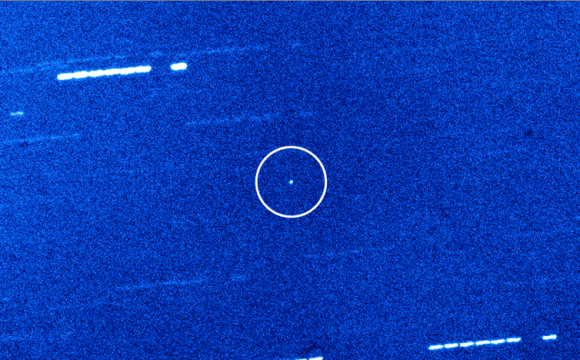

On October 19th, 2017, the Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System-1 (Pan-STARRS-1) in Hawaii announced the first-ever detection of an interstellar asteroid, named 1I/2017 U1 (aka. ‘Oumuamua). Originally thought to be a comet, this interstellar visitor quickly became the focus of follow-up studies that sought to determine its origin, structure, composition, and rule out the possibility that it was an alien spacecraft!

While ‘Oumuamua is the first known example of an interstellar asteroid reaching our Solar System, scientists have long suspected that such visitors are a regular occurrence. Aiming to determine just how common, a team of researchers from Harvard University conducted a study to measure the capture rate of interstellar asteroids and comets, and what role they may play in the spread of life throughout the Universe.

The study, titled “Implications of Captured Interstellar Objects for Panspermia and Extraterrestrial Life“, recently appeared online and is being considered for publication in The Astrophysical Journal. The study was conducted by Manasavi Lingam, a postdoc at the Harvard Institute for Theory and Computation (ITC), and Abraham Loeb, the chairman of the ITC and a researcher at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA).

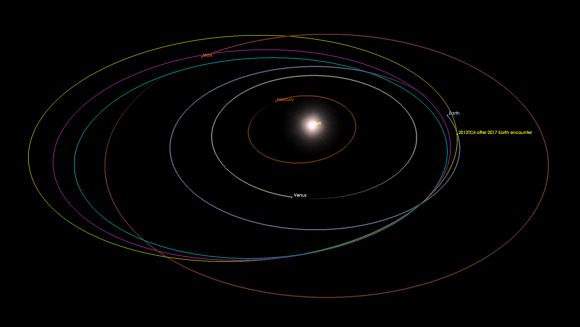

For the sake of their study, Lingam and Loeb constructed a three-body gravitational model, where the physics of three bodies are used to compute their respective trajectories and interactions with one another. In Lingam and Loeb’s model, Jupiter and the Sun served as the two massive bodies while a far less massive interstellar object served as the third. As Dr. Loeb explained to Universe Today via email:

“The combined gravity of the Sun and Jupiter acts as a ‘fishing net’. We suggest a new approach to searching for life, which is to examine the interstellar objects captured by this fishing net instead of the traditional approach of looking through telescope or traveling with spacecrafts to distant environments to do the same.”

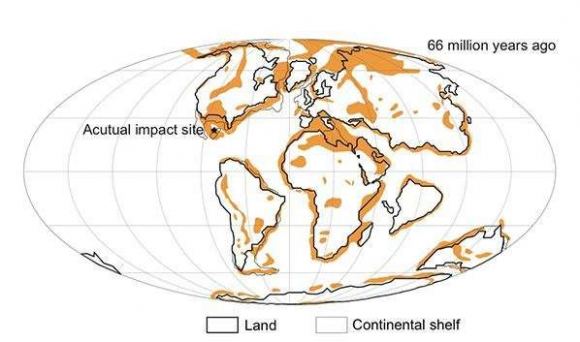

Using this model, the pair then began calculating the rate at which objects comparable in size to ‘Oumuamua would be captured by the Solar System, and how often such objects would collide with the Earth over the course of its entire history. They also considered the Alpha Centauri system as a separate case for the sake of comparison. In this binary system, Alpha Centauri A and B serve as the two massive bodies and an interstellar asteroid as the third.

As Dr. Lingam indicated:

“The frequency of these objects is determined from the number density of such objects, which has been recently updated based on the discovery of ‘Oumuamua. The size distribution of these objects is unknown (and serves as a free parameter in our model), but for the sake of obtaining quantitative results, we assumed that it was similar to that of comets within our Solar System.”

In the end, they determined that a few thousands captured objects might be found within the Solar system at any time – the largest of which would be tens of km in radius. For the Alpha Centauri system, the results were even more interesting. Based on the likely rate of capture, and the maximum size of a captured object, they determined that even Earth-sized objects could have been captured in the course of the system’s history.

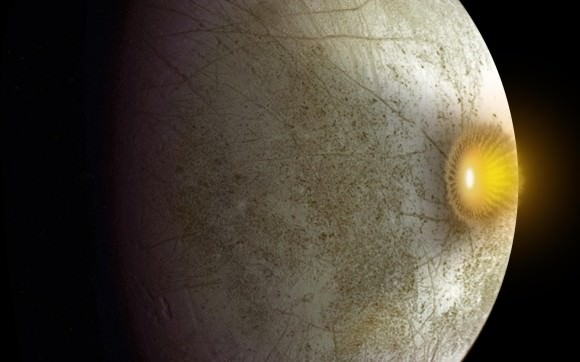

In other words, Alpha Centauri may have picked up some rogue planets over time, which would have had drastic impact on the evolution of the system. In this vein, the authors also explored how objects like ‘Oumuamua could have played a role in the distribution of life throughout the Universe via rocky bodies. This is a variation on the theory of lithopanspermia, where microbial life is shared between planets thanks to asteroids, comets and meteors.

In this scenario, interstellar asteroids, which originate in distant star systems, would be the be carriers of microbial life from one system to another. If such asteroids collided with Earth in the past, they could be responsible for seeding our planet and leading to the emergence of life as we know it. As Lingam explained:

“These interstellar objects could either crash directly into a planet and thus seed it with life, or be captured into the planetary system and undergo further collisions within that system to yield interplanetary panspermia (the second scenario is more likely when the captured object is large, for e.g. a fraction of the Earth’s radius).”

In addition, Lingam and Loeb offered suggestions on how future visitors to our Solar System could be studied. As Lingam summarized, the key would be to look for specific kinds of spectra from objects in our Solar Systems:

“It may be possible to look for interstellar objects (captured/unbound) in our Solar system by looking at their trajectories in detail. Alternatively, since many objects within the Solar system have similar ratios of oxygen isotopes, finding objects with very different isotopic ratios could indicate their interstellar origin. The isotope ratios can be determined through high-resolution spectroscopy if and when interstellar comets approach close to the Sun.”

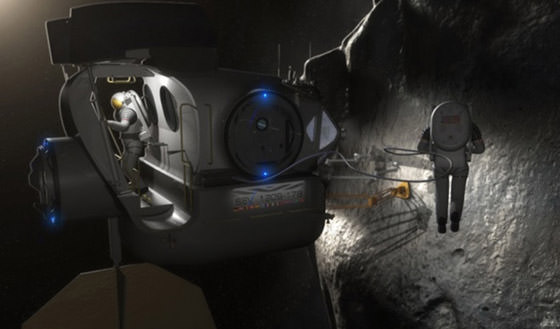

“The simplest way to single out the objects who originated outside the Solar System, is to examine the abundance ratio of oxygen isotopes in the water vapor that makes their cometary tails,” added Loeb. “This can be done through high resolution spectroscopy. After identifying a trapped interstellar object, we could launch a probe that will search on its surface for signatures of primitive life or artifacts of a technological civilization.”

It would be no exaggeration to say that the discovery of ‘Oumuamua has set off something of a revolution in astronomy. In addition to validating something astronomers have long suspected, it has also provided new opportunities for research and the testing of scientific theories (such as lithopanspermia).

In the future, with any luck, robotic missions will be dispatched to these bodies to conduct direct studies and maybe even sample return missions. What these reveal about our Universe, and maybe even the spread of life throughout, is sure to be very illuminating!

Further Reading: arXiv