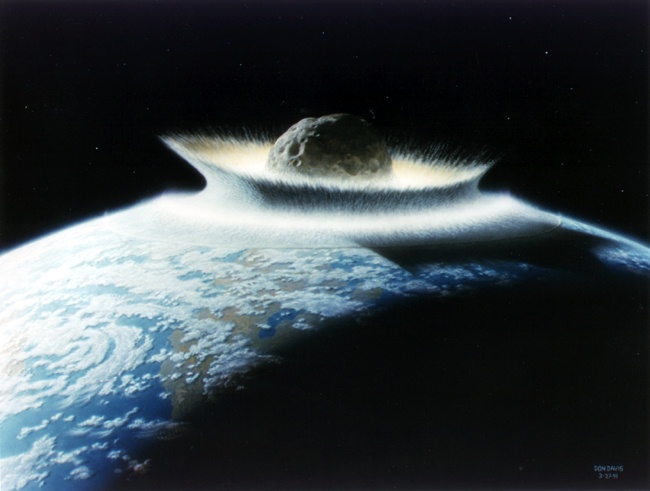

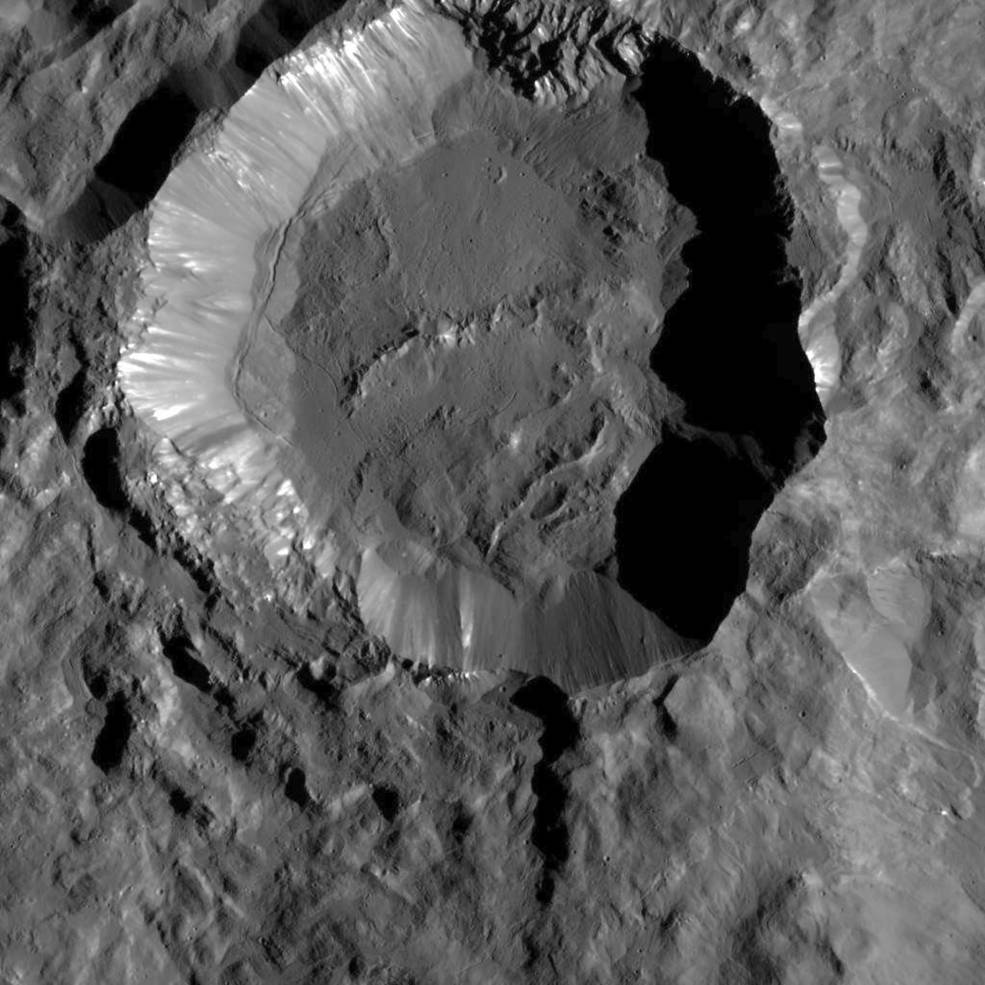

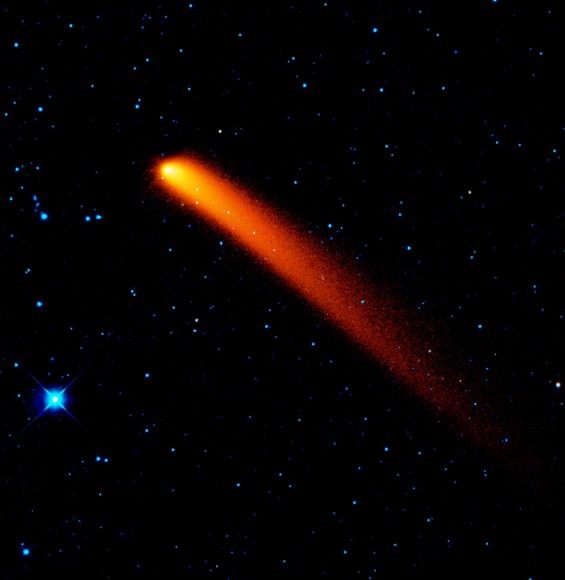

All over the Earth, there is a buried layer of sediment rich in iridium called the Cretaceous Paleogene-Boundary (K-Pg.) This sediment is the global signature of the 10-km-diameter asteroid that killed off the dinosaurs—and about 50% of all other species—66 million years ago. Now, in an effort to understand how life recovered after that event, scientists are going to drill down into the site where the asteroid struck—the Chicxulub Crater off the coast of Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula.

The end-Cretaceous extinction was a global catastrophe, and a lot is already known about it. We’ve learned a lot about the physical effects of the strike on the impact area from oil and gas drilling in the Gulf of Mexico. According to data from that drilling, released on February 5th in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, the asteroid that struck Earth displaced approximately 200,000 cubic km (48,000 cubic miles) of sediment. That’s enough to fill the largest of the Great Lakes—Lake Superior—17 times.

The Chicxulub impact caused earthquakes and tsunamis that first loosened debris, then swept it from nearby areas like present-day Florida and Texas into the Gulf basin itself. This layer is hundreds of meters thick, and is hundreds of kilometers wide. It covers not only the Gulf of Mexico, but also the Caribbean and the Yucatan Peninsula.

In April, a team of scientists from the University of Texas and the National University of Mexico will spend two months drilling in the area, to gain insight into how life recovered after the impact event. Research Professor Sean Gulick of the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics told CNN in an interview that the team already has a hypothesis for what they will find. “We expect to see a period of no life initially, and then life returning and getting more diverse through time.”

Scientists have been wanting to drill in the impact region for some time, but couldn’t because of commercial drilling activity. Allowing this team to study the region directly will build on what is already known: that this enormous deposit of sediment happened over a very short period of time, possibly only a matter of days. The drilling will also help paint a picture of how life recovered by looking at the types of fossils that appear. Some scientists think that the asteroid impact would have lowered the pH of the oceans, so the fossilized remains of animals that can endure greater acidity would be of particular interest.

The Chicxulub impact was a monumental event in the history of the Earth, and it was extremely powerful. It may have been a billion times more powerful than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Other than the layer of sediment laid down near the site of the impact itself, its global effects probably included widespread forest fires, global cooling from debris in the atmosphere, and then a period of high temperatures caused by an increase in atmospheric CO2.

We already know what will happen if an asteroid this size strikes Earth again—global devastation. But drilling in the area of the impact will tell us a lot about how geological and ecological processes respond to this type of devastation.