One of the better asteroid occultations of 2014 is coming right up tonight, and Canadian and U.S. observers in the northeast have a front row seat.

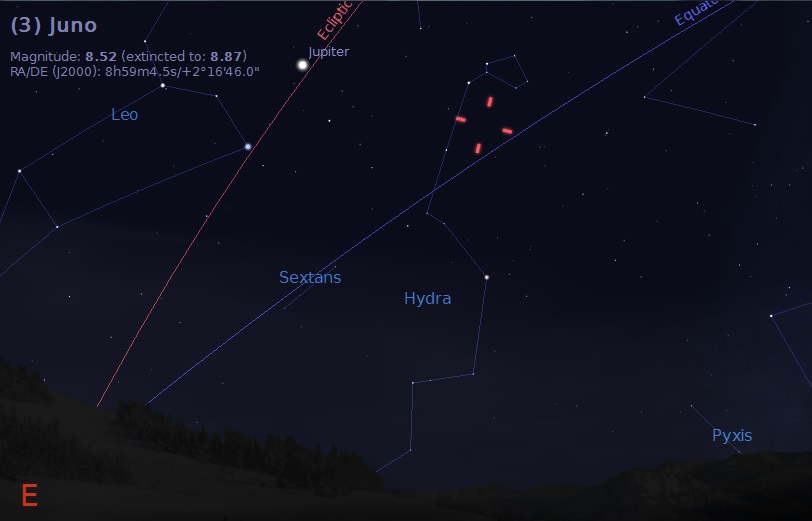

The event occurs in the early morning hours of Thursday, November 20th, when the asteroid 3 Juno occults the 7.4 magnitude star SAO 117176. The occultation kicks off in the wee hours as the 310 kilometre wide “shadow” of 3 Juno touches down and crosses North America from 6:54 to 6:57 Universal Time (UT), which is 12:54 to 12:57 AM Central, or 1:54 to 1:57 AM Eastern Standard Time.

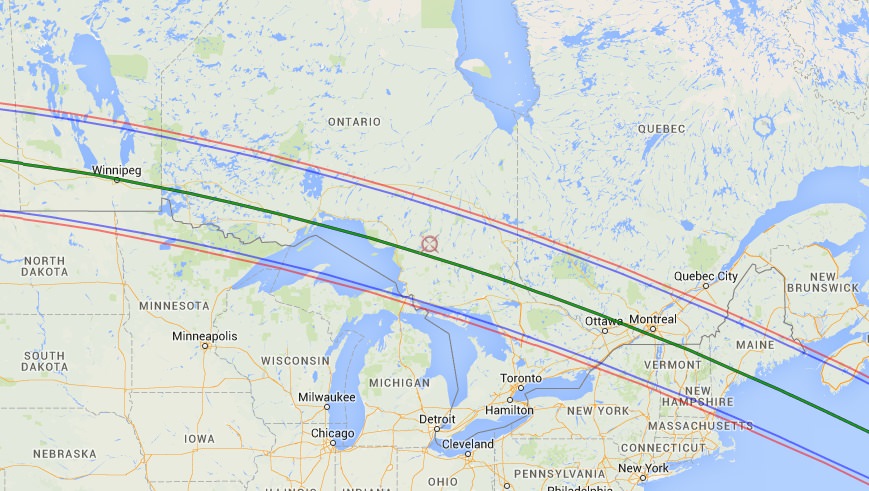

The maximum predicted length of the occultation for observers based along the centerline is just over 27 seconds. Note that 3 Juno also shines at magnitude +8.5, so both it and the star are binocular objects. The event will sweep across Winnipeg and Lake of the Woods straddling the U.S. Canadian border, just missing Duluth Minnesota before crossing Lake Superior and over Ottawa and Montreal and passing into northern Vermont and New Hampshire. Finally, the path crosses over Portland Maine, and heads out to sea over the Atlantic Ocean.

Don’t live along the path? Observers worldwide will still see a close pass of 3 Juno and the +7th magnitude star as both do their best to impersonate a close binary pair. If you’ve never crossed spotting 3 Juno off of your astro-“life list,” now is a good time to try.

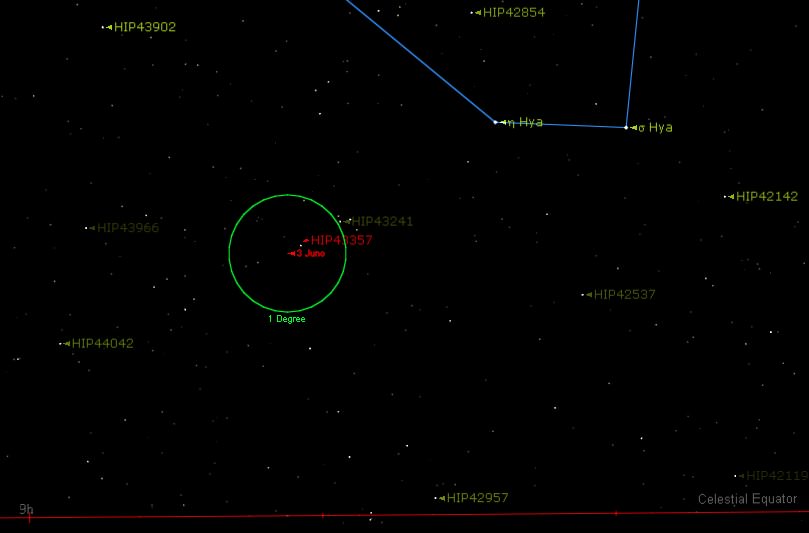

The position of the target star HIP43357/SAO 117176 is:

Right Ascension: 8 Hours 49’ 54”

Declination: +2° 21’ 44”

Generally, the farther east you are along the track, the higher the pair will be above the horizon when the event occurs, and the better your observing prospects will be in terms of altitude or elevation. From Portland Maine — the last port of call for the shadow of 3 Juno on dry land — the pair will be 35 degrees above the horizon in the constellation of Hydra.

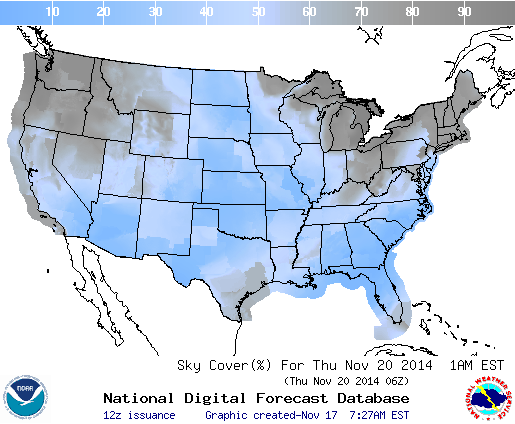

As always, the success in observing any astronomical event is at the whim of the weather, which can be fickle in North America in November. As of 48 hours out from the occultation, weather prospects look dicey, with 70%-90% cloud cover along the track. But remember, you don’t necessarily need a fully clear sky to make a successful observation… just a clear view near the head of Hydra asterism. Remember the much anticipated occultation of Regulus by the asteroid 163 Erigone earlier this year? Alas, it went unrecorded due to pesky but pervasive cloud cover. Perhaps this week’s occultation will fall prey to the same, but it’s always worth a try. In asteroid occultations as in free throws, you miss 100% of the shots that you don’t take!

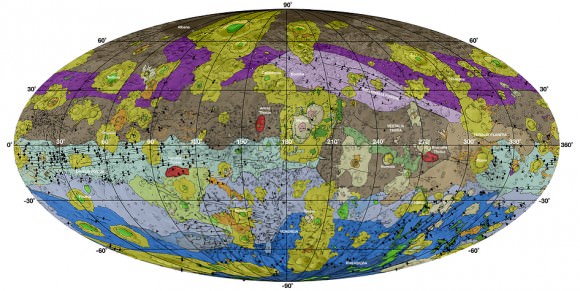

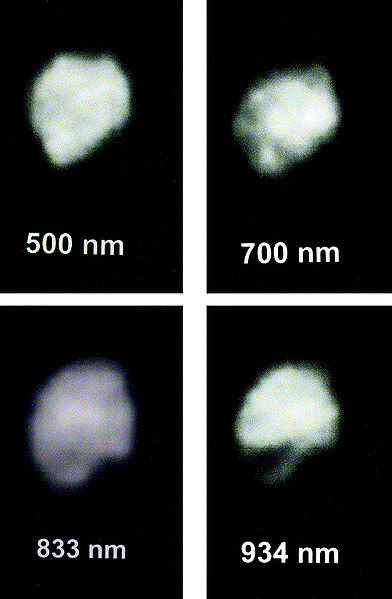

Why study asteroid occultations? Sure, it’s cool to see a star wink out as an asteroid passes in front of it, but there’s real science to be done as well. Expect the star involved in Thursday’s occultation to dip down about two magnitudes (six times) in brightness. The International Occultation Timing Association (IOTA) is always seeking careful measurements of asteroid occultations of bright stars. If enough observations are made along the track, a shape profile of the target asteroid emerges. And the possible discovery of an “asteroid moon” is not unheard of using this method, as the background star winks out multiple times.

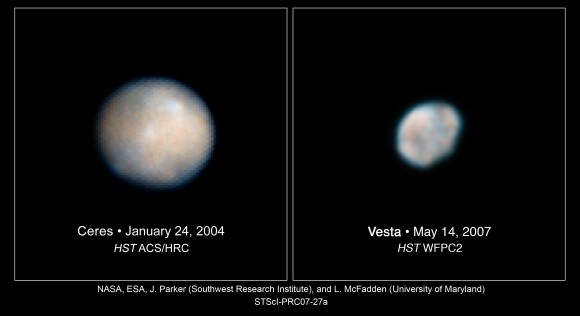

3 Juno was discovered crossing Cetus by astronomer Karl Harding on September 1st, 1804 from the Lilienthal Observatory in Germany. The 3rd asteroid discovered after 1 Ceres and 2 Pallas, 3 Juno ranks 5th in size at an estimated 290 kilometres in diameter. In the early 19th century, 3 Juno was also considered a planet along with these other early discoveries, until the ranks swelled to a point where the category of asteroid was introduced. A denizen of the asteroid belt, 3 Juno roams from 2 A.U.s from the Sun at perigee to 3.4 A.U.s at apogee, and can reach a maximum brightness of +7.4th magnitude as seen from the Earth. No space mission has ever been dispatched to study 3 Juno, although we will get a good look at its cousin 1 Ceres next April when NASA’s Dawn spacecraft enters orbit around the king of the asteroids.

3 Juno reaches opposition and its best observing position on January 29th, 2015.

3 Juno also has an interesting place in the history of asteroid occultations. The first ever predicted and successfully observed occultation of a star by an asteroid involved 3 Juno on February 19th, 1958. Another occultation involving the asteroid on December 11th, 1979 was even more widely observed. Only a handful of such events were caught prior to the 1990s, as it required ultra-precise computation and knowledge of positions and orbits. Today, dozens of asteroid occultations are predicted each month worldwide.

Observing an asteroid occultation can be challenging but rewarding. You can watch Thursday’s event with binoculars, but you’ll want to use a telescope to make a careful analysis. You can either run video during the event, or simply watch and call out when the star dims and brightens as you record audio. Precise timing and pinpointing your observing location via GPS is key, and human reaction time plays a factor as well. Be sure to locate the target star well beforehand. For precise time, you can run WWV radio in the background.

And finally, you also might see… nothing. Asteroid paths have a small amount of uncertainty to them, and although these negative observations aren’t as thrilling to watch, they’re important to the overall scientific effort.

Good luck, and let us know of your observational tales of anguish and achievement!