The recent meteor explosion over Chelyabinsk brought to the forefront a topic that has worried astronomers for years, namely that an impactor from space could cause widespread human fatalities. Indeed, the thousand+ injured recently in Russia was a wake-up call. Should humanity be worried about impactors? “Hell yes!” replied astronomer Neil deGrasse Tyson to CNN’s F. Zakharia .

The geological and biological records attest to the fact that some impactors have played a major role in altering the evolution of life on Earth, particularly when the underlying terrestrial material at the impact site contains large amounts of carbonates and sulphates. The dating of certain large impact craters (50 km and greater) found on Earth have matched events such as the extinction of the Dinosaurs (Hildebrand 1993, however see also G. Keller’s alternative hypothesis). Ironically, one could argue that humanity owes its emergence in part to the impactor that killed the Dinosaurs.

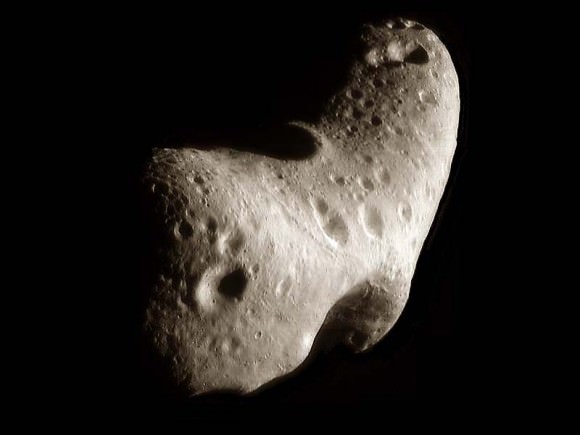

Only rather recently did scientists begin to widely acknowledge that sizable impactors from space strike Earth.

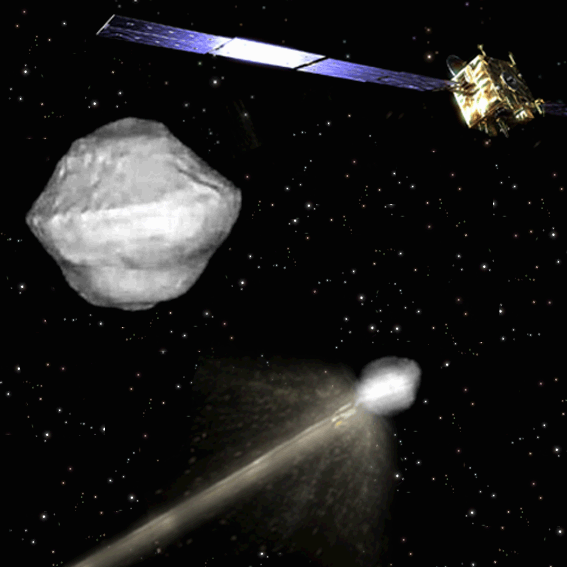

“It was extremely important in that first intellectual step to recognize that, yes, indeed, very large objects do fall out of the sky and make holes in the ground,” said Eugene Shoemaker. Shoemaker was a co-discoverer of Shoemaker-Levy 9, which was a fragmented comet that hit Jupiter in 1994 (see video below).

Hildebrand 1993 likewise noted that, “the hypothesis that catastrophic impacts cause mass extinctions has been unpopular with many geologists … some geologists still regard the existence of ~140 known impact craters on the Earth as unproven despite compelling evidence to the contrary.”

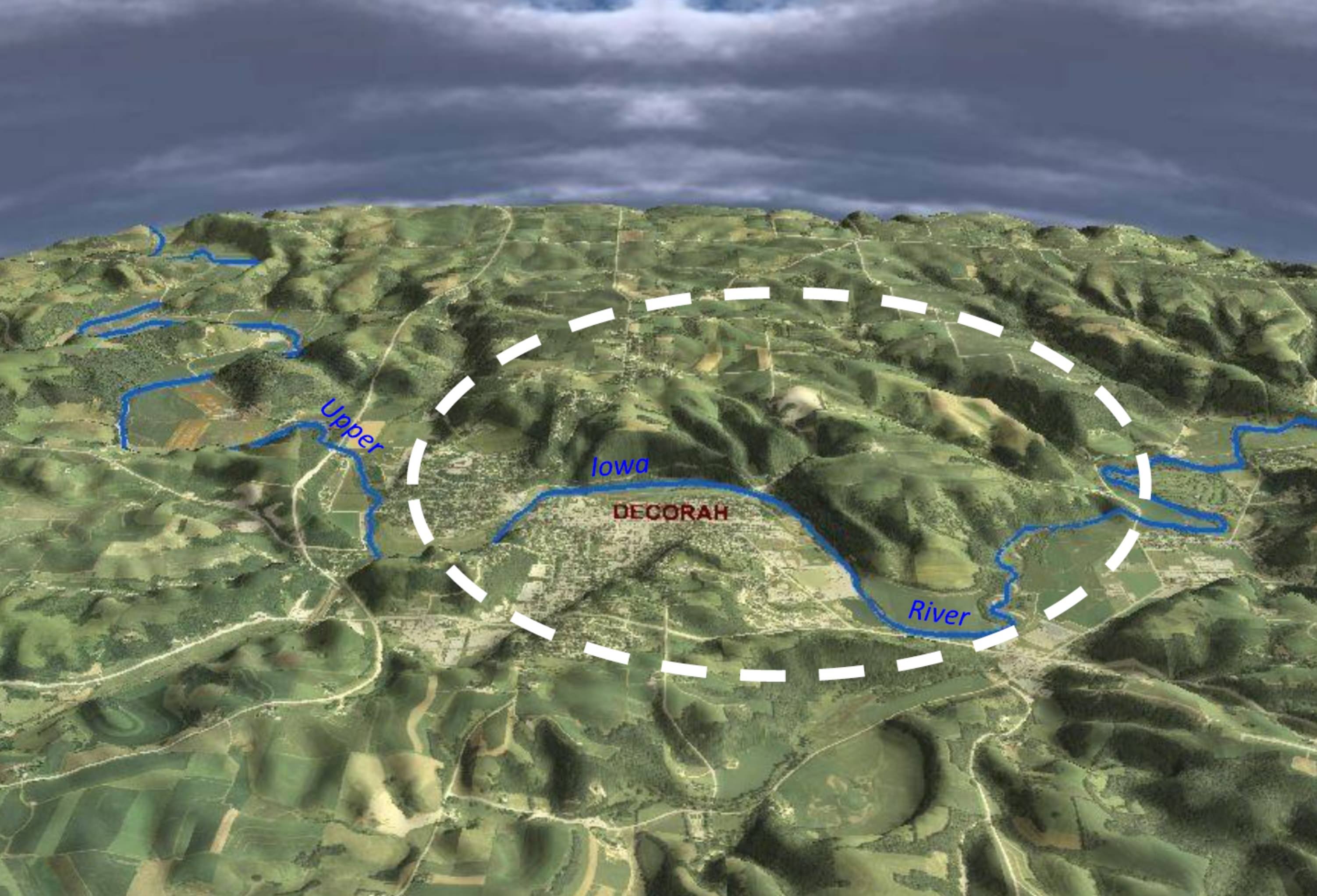

Beyond the asteroid that struck Mexico 65 million years ago and helped end the reign of the dinosaurs, there are numerous lesser-known terrestrial impactors that also appear destructive given their size. For example, at least three sizable impactors struck Earth ~35 million years ago, one of which left a 90 km crater in Siberia (Popigai). At least two large impactors occurred near the Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary (Morokweng and Mjolnir), and the latter may have been the catalyst for a tsunami that dwarfed the recent event in Japan (see also the simulation for the tsunami generated by the Chicxulub impactor below).

Glimsdal et al. 2007 note, “it is clear that both the geological consequences and the tsunami of an impact of a large asteroid are orders off magnitude larger than those of even the largest earthquakes recorded.”

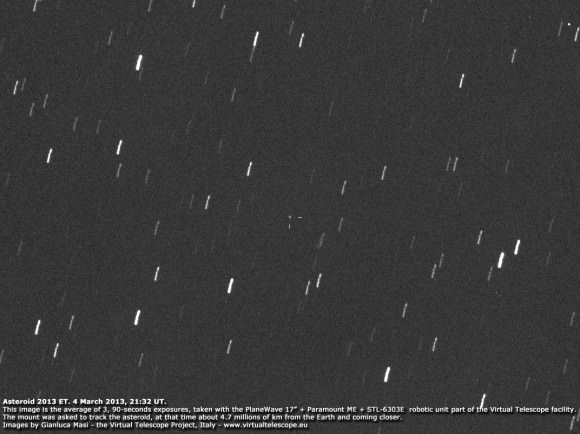

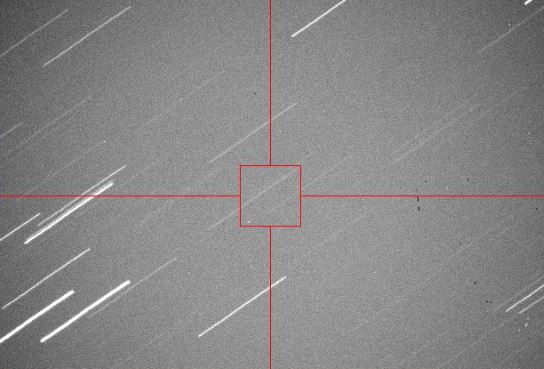

However, in the CNN interview Neil deGrasse Tyson remarked that we’ll presumably identify the larger impactors ahead of time, giving humanity the opportunity to enact a plan to (hopefully) deal with the matter. Yet he added that often we’re unable to identify smaller objects in advance, and that is problematic. The meteor that exploded over the Urals a few weeks ago is an example.

In recent human history the Tunguska event, and the asteroid that recently exploded over Chelyabinsk, are reminders of the havoc that even smaller-sized objects can cause. The Tunguska event is presumed to be a meteor that exploded in 1908 over a remote forested area in Siberia, and was sufficiently powerful to topple millions of trees (see image below). Had the event occurred over a city it may have caused numerous fatalities.

Mark Boslough, a scientist who studied Tunguska noted, “That such a small object can do this kind of destruction suggests that smaller asteroids are something to consider … such collisions are not as improbable as we believed. We should be making more efforts at detecting the smaller ones than we have till now.”

Neil deGrasse Tyson hinted that humanity was rather lucky that the recent Russian fireball exploded about 20 miles up in the atmosphere, as its energy content was about 30 times larger than the Hiroshima explosion. It should be noted that the potential negative outcome from smaller impactors increases in concert with an increasing human population.

So how often do large bodies strike Earth, and is the next catastrophic impactor eminent? Do such events happen on a periodic basis? Scientists have been debating those questions and no consensus has emerged. Certain researchers advocate that large impactors (leaving craters greater than 35 km) strike Earth with a period of approximately 26-35 million years.

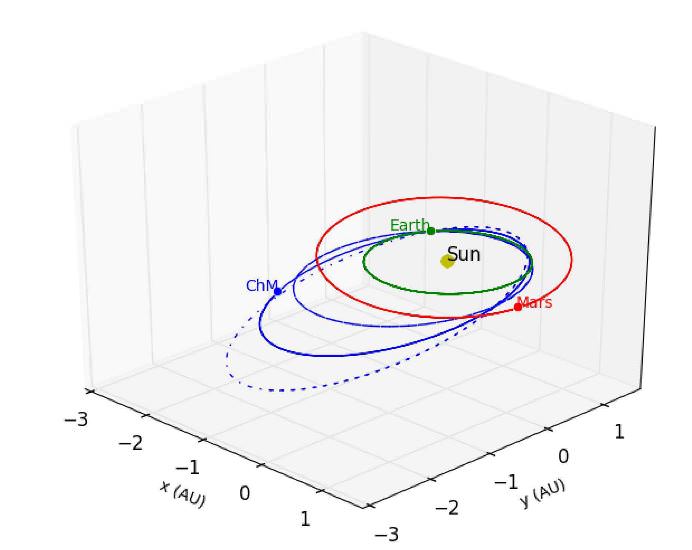

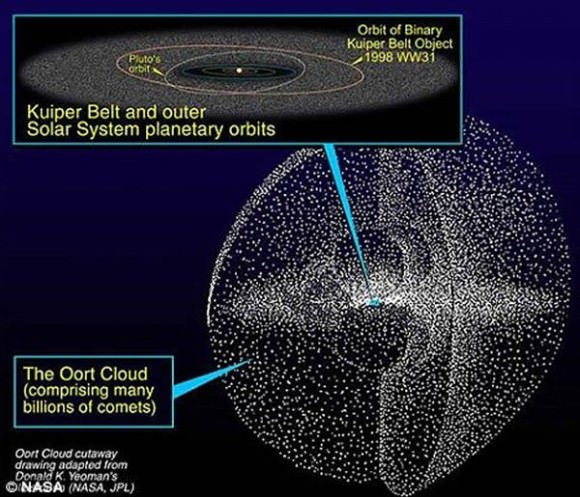

The putative periodicity (i.e., the Shiva hypothesis) is often linked to the Sun’s vertical oscillations through the plane of the Milky Way as it revolves around the Galaxy, although that scenario is likewise debated (as is many of the assertions put forth in this article). The Sun’s motion through the denser part of the Galactic plane is believed to trigger a comet shower from the Oort Cloud. The Oort Cloud is theorized to be a halo of loosely-bound comets that encompasses the periphery of the Solar System. Essentially, there exists a main belt of asteroids between Mars and Jupiter, a belt of comets and icy bodies located beyond Neptune called the Kuiper belt, and then the Oort Cloud. A lower-mass companion to the Sun was likewise considered as a perturbing source of Oort Cloud comets (“The Nemesis Affair” by D. Raup).

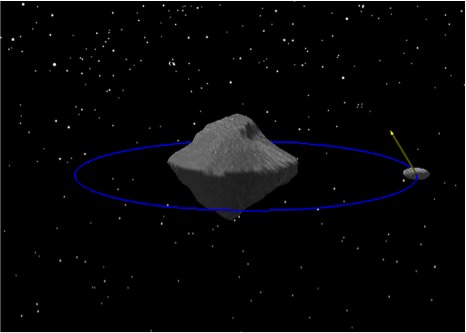

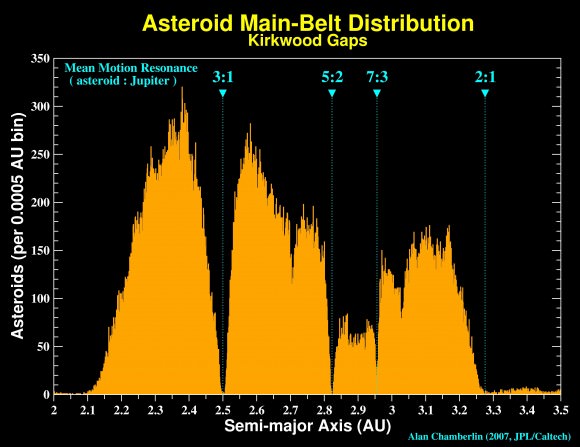

The aforementioned theory pertains principally to periodic comets showers, however, what mechanism can explain how asteroids exit their otherwise benign orbits in the belt and enter the inner solar system as Earth-crossers? One potential (stochastic) scenario is that asteroids are ejected from the belt via interactions with the planets through orbital resonances. Evidence for that scenario is present in the image below, which shows that regions in the belt coincident with certain resonances are nearly depleted of asteroids. A similar trend is seen in the distribution of icy bodies in the Kuiper belt, where Neptune (rather than say Mars or Jupiter) may be the principal scattering body. Note that even asteroids/comets not initially near a resonance can migrate into one by various means (e.g., the Yarkovsky effect).

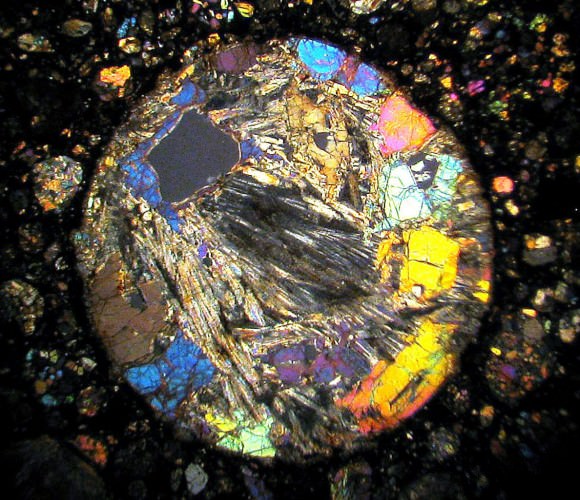

Indeed, if an asteroid in the belt were to breakup (e.g., collision) near a resonance, it would send numerous projectiles streaming into the inner solar system. That may help partly explain the potential presence of asteroid showers (e.g., the Boltysh and Chicxulub craters both date to near 65 million years ago). In 2007, a team argued that the asteroid which helped end the reign of the Dinosaurs 65 million years ago entered an Earth-crossing orbit via resonances. Furthermore, they noted that asteroid 298 Baptistina is a fragment of that Dinosaur exterminator, and it can be viewed in the present orbiting ~2 AU from the Sun. The team’s specific assertions are being debated, however perhaps more importantly: the underlying transport mechanism that delivers asteroids from the belt into Earth-crossing orbits appears well-supported by the evidence.

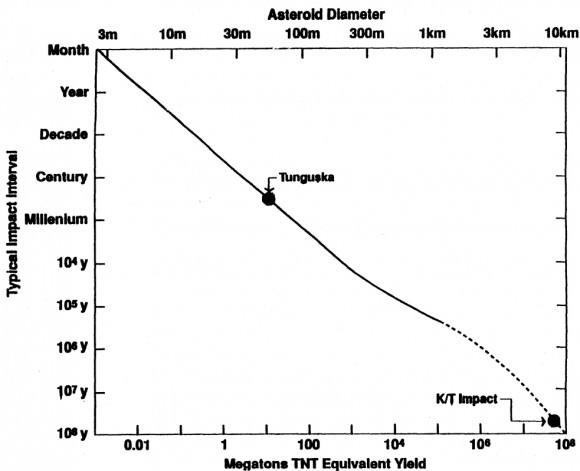

Thus it appears that the terrestrial impact record may be tied to periodic and random phenomena, and comet/asteroid showers can stem from both. However, reconstructing that terrestrial impact record is rather difficult as Earth is geologically active (by comparison to the present Moon where craters from the past are typically well preserved). Thus smaller and older impactors are undersampled. The impact record is also incomplete since a sizable fraction of impactors strike the ocean. Nevertheless, an estimated frequency curve for terrestrial impacts as deduced by Rampino and Haggerty 1996 is reproduced below. Note that there is considerable uncertainty in such determinations, and the y-axis in the figure highlights the “Typical Impact Interval”.

In sum, as noted by Eugene Shoemaker, large objects do indeed fall out of the sky and cause damage. It is unclear when in the near or distant future humanity will be forced to rise to the challenge and counter an incoming larger impactor, or again deal with the consequences of a smaller impactor that went undetected and caused human injuries (the estimated probabilities aren’t reassuring given their uncertainty and what’s in jeopardy). Humanity’s technological progress and scientific research must continue unabated (and even accelerated), thereby affording us the tools to better tackle the described situation when it arises.

Is discussion of this topic fear mongering and alarmist in nature? The answer should be obvious given the fireball explosion that happened recently over the Ural mountains, the Tunguska event, and past impactors. Given the stakes excessive vigilance is warranted.

Fareed Zakharia’s discussion with Neil deGrasse Tyson is below.

The interested reader desiring additional information will find the following pertinent: the Earth Impact Database, Hildebrand 1993, Rampino and Haggerty 1996, Stothers et al. 2006, Glimsdal et al. 2007, Bottke et al. 2007, Jetsu 2011, G. Keller’s discussion concerning the end of the Dinosaurs, “T. rex and the Crater of Doom” by W. Alvarez, “The Nemesis Affair” by D. Raup, “Collision Earth! The Threat from Outer Space” by P. Grego. **Note that there is a diverse spectrum of opinions on nearly all the topics discussed here, and our understanding is constantly evolving. There is much research to be done.