[/caption]

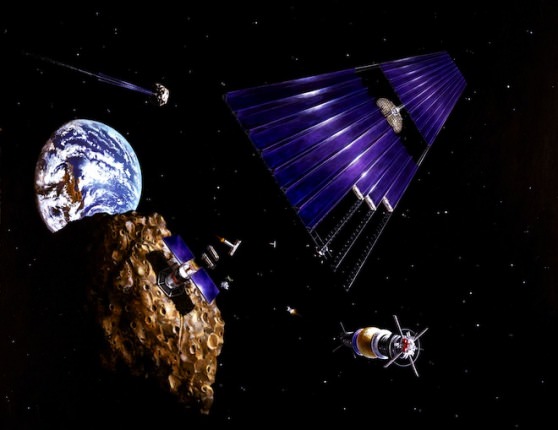

Last week a new company backed by a number of high-tech billionaires said they would be announcing a new space venture, and there was plenty of speculation of what the company –– called Planetary Resources — would be doing. Many ventured the company would be an asteroid mining outfit, and now, the company has revealed its purpose really is to focus on extracting precious resources such as metals and rare minerals from asteroids. “This innovative start-up will create a new industry and a new definition of ‘natural resources,’” the group said.

Is this pie in the sky or a solid investment plan?

It turns out this company has been in existence for about three years, working quietly in the background, assembling their plan.

The group includes X PRIZE CEO Peter Diamandis, Space Adventures founder Eric Anderson, Google executives K. Ram Shriram, Larry Page and Eric Schmidt, filmmaker James Cameron, former Microsoft chief software architect Charles Simonyi — a two-time visitor to the International Space Station — and Ross Perot Jr.

Even though their official press conference isn’t until later today, many of the founders started talking late yesterday. The group will initially focus on developing Earth orbiting telescopes to scan for the best asteroids, and later, create extremely low-cost robotic spacecraft for surveying missions.

A demonstration mission in orbit around Earth is expected to be launched within two years, according to the said company co-founders, and within five to 10 years, they hope to go from selling observation platforms in orbit to prospecting services, then travel to some of the thousands of asteroids that pass relatively close to Earth and extract their raw materials and bring them back to Earth.

But this company also plans to use the water found in asteroids to create orbiting fuel depots, which could be used by NASA and others for robotic and human space missions.

“We have a long view. We’re not expecting this company to be an overnight financial home run. This is going to take time,” Anderson said in an interview with Reuters.

President and Chief Engineer Chris Lewicki talked with Phil Plait yesterday and said “This is an attempt to make a permanent foothold in space. We’re going to enable this piece of human exploration and the settlement of space, and develop the resources that are out there.”

Lewicki was Flight Director for the NASA’s Spirit and Opportunity Mars rover missions, and also Mission Manager for the Mars Phoenix lander surface operations. He added that the plan structure is reminiscent of that of Apollo: have a big goal in mind, but make sure the steps along the way are practical.

Another of the aims of Planetary Resources is to open deep-space exploration to private industry, much like the $10 million Ansari X Prize competition, which Diamandis created. In previous talks, Diamandis has estimated that a small asteroid is worth about “20 trillion dollars in the platinum group metal marketplace.”

“The resources of Earth pale in comparison to the wealth of the solar system,” Eric Anderson told Wired.

The company will reveal more details in their press conference today (April 24) at 10:30 AM PDT | 12:30 PM CDT | 1:30 PM EDT | 5:30 UTC. You can watch at this link.

Sources: Bad Astronomy, Wired, Reuters