[/caption]

Using and getting the most out of robotic astronomy

Whilst nothing in the field of amateur astronomy beats the feeling of being outside looking up at the stars, the inclement weather many of us have to face at various times of year, combined with the task of setting up and then packing away equipment on a nightly basis, can be a drag. Those of us fortunate enough to have observatories don’t face that latter issue, but still face the weather and usually the limits of our own equipment and skies.

Another option to consider is using a robotic telescope. From the comfort of your home you can make incredible observations, take outstanding astrophotos, and even make key contributions to science!

The main elements which make robotic telescopes appealing to many amateur astronomers are based around 3 factors. The first is that usually, the equipment being offered is generally vastly superior to that which the amateur has in their home observatory. Many of the robotic commercial telescope systems, have large format mono CCD cameras, connected to high precision computer controlled mounts, with superb optics on top, typically these setups start in the $20-$30,000 price bracket and can run up in to the millions of dollars.

Combined with usually well defined and fluid workflow processes which guide even a novice user through the use of the scope and then acquisition of images, automatically handling such things as dark and flat fields, makes it a much easier learning curve for many as well, with many of the scopes specifically geared for early grade school students.

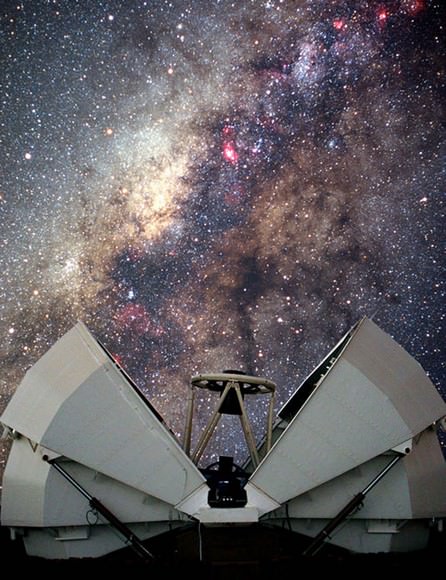

The second factor is geographic location. Many of the robotic sites are located in places where average rainfall is a lot lower than say somewhere like the UK or North Eastern United States for example, with places like New Mexico and Chile in particular offering almost completely clear dry skies year round. Robotic scopes tend to see more sky than most amateur setups, and as they are being controlled over the Internet, you yourself don’t even have to get cold outside in the depths of winter. The beauty of the geographic location aspect is that in some cases, you can do your astronomy during the daytime, as the scopes may be on the other side of the world.

The third is ease of use, as it’s nothing more than a reasonably decent laptop, and solid broadband connection that’s required. The only thing you need worry about is your internet connection dropping, not your equipment failing to work. With scopes like the Faulkes or Liverpool Telescopes, ones I use a lot, they can be controlled from something as modest as a netbook or even an Android/iPad/iPhone, easily. The issues with CPU horsepower usually comes down to the image processing after you have taken your pictures.

Software applications like the brilliant Maxim DL by Diffraction Limited which is commonly used for image post processing in amateur and even professional astronomy, handles the FITS file data which robotic scopes will deliver. This is commonly the format images are saved in with professional observatories, and the same applies with many home amateur setups and robotic telescopes. This software requires a reasonably fast PC to work efficiently, as does the other stalwart of the imaging community, Adobe Photoshop. There are some superb and free applications which can be used instead of these two bastions of the imaging fraternity, like the excellent Deep Sky stacker, and IRIS, along with the interestingly named “GIMP” which is variant on the Photoshop theme, but free to use.

Some people may say just handling image data or a telescope over the internet detracts from real astronomy, but it’s how professional astronomers work day in day out, usually just doing data reduction from telescopes located on the other side of the world. Professionals can wait years to get telescope time, and even then rather than actually being a part of the imaging process, will submit imaging runs to observatories, and wait for the data to roll in. (If anyone wants to argue this fact…just say “Try doing eyepiece astronomy with the Hubble”)

The process of using and imaging with a robotic telescope still requires a level of skill and dedication to guarantee a good night of observing, be it for pretty pictures or real science or both.

Location Location Location

The location for a robotic telescope is critical as if you want to image some of the wonders of the Southern Hemisphere, which those of us in the UK or North America will never see from home, then you’ll need to pick a suitably located scope. Time of day is also important for access, unless the scope system allows an offline queue management approach, whereby you schedule it to do your observations for you and just wait for the results. Some telescopes utilise a real time interface, where you literally control the scope live from your computer, typically through a web browser interface. So depending on where in the world it is, you may be in work, or it may be at a very unhealthy hour in the night before you can access your telescope, it’s worth considering this when you decide which robotic system you wish to be a part of.

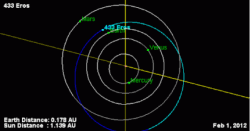

Telescopes like the twin Faulkes 2-metre scopes, which are based on the Hawaiian island of Maui, atop a mountain, and Siding Spring, Australia, next to the world famous Anglo Australian Observatory, operate during usual school hours in the UK, which means night time in the locations where the scopes live. This is perfect for children in western Europe who wish to use research grade professional technology from the classroom, though the Faulkes scopes are also used by schools and researchers in Hawaii.

The type of scope/camera you choose to use, will ultimately also determine what it is you image. Some robotic scopes are configured with wide field large format CCD’s connected to fast, low focal ratio telescopes. These are perfect for creating large sky vistas encompassing nebulae and larger galaxies like Messier 31 in Andromeda. For imaging competitions like the Astronomy Photographer of the Year competition, these wide field scopes are perfect for the beautiful skyscapes they can create.

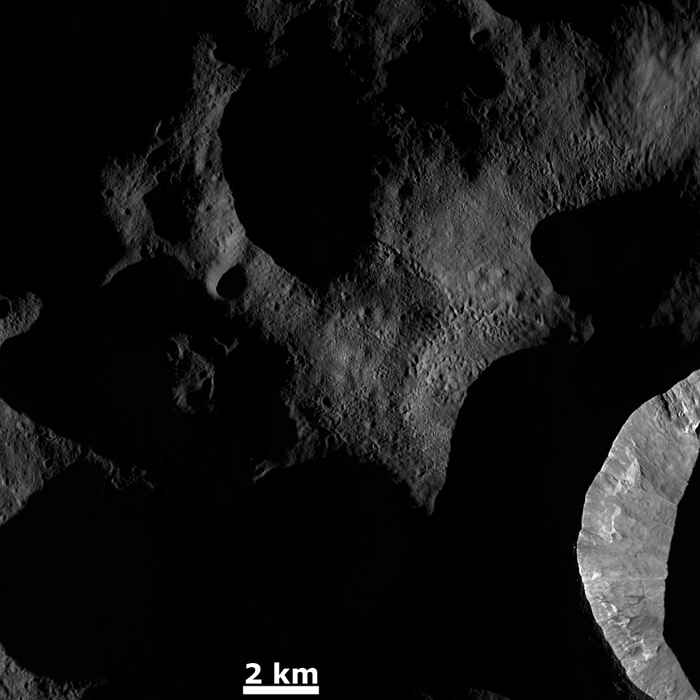

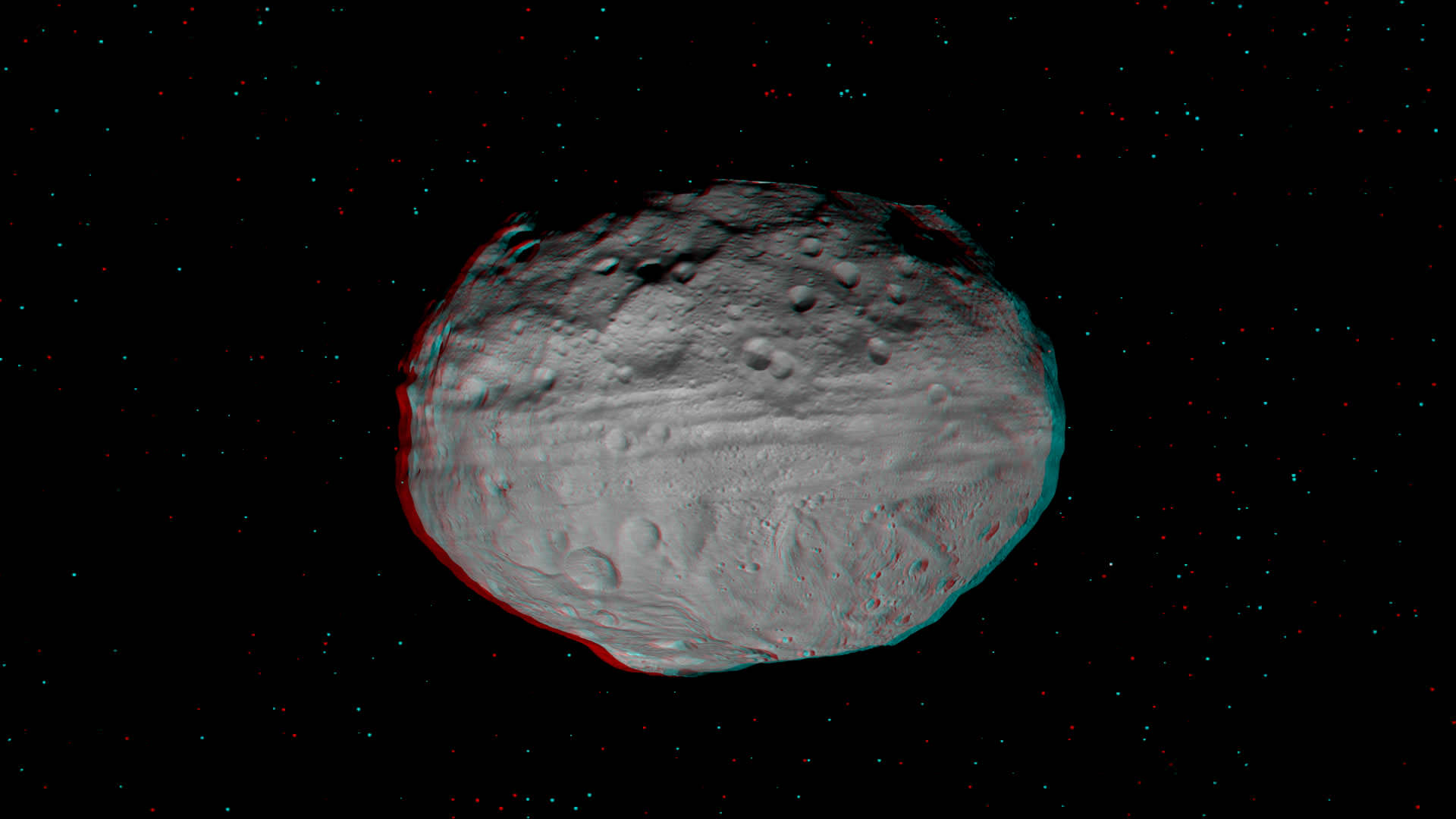

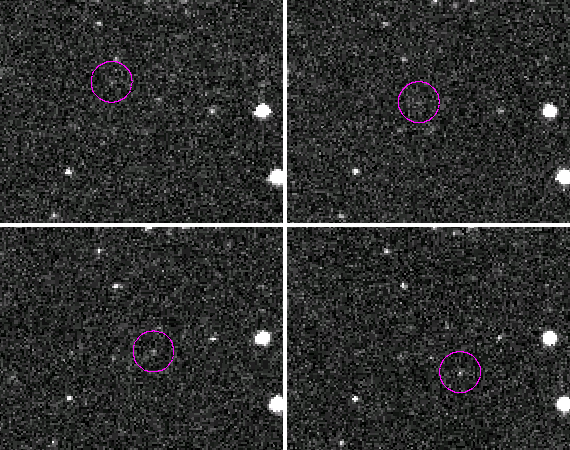

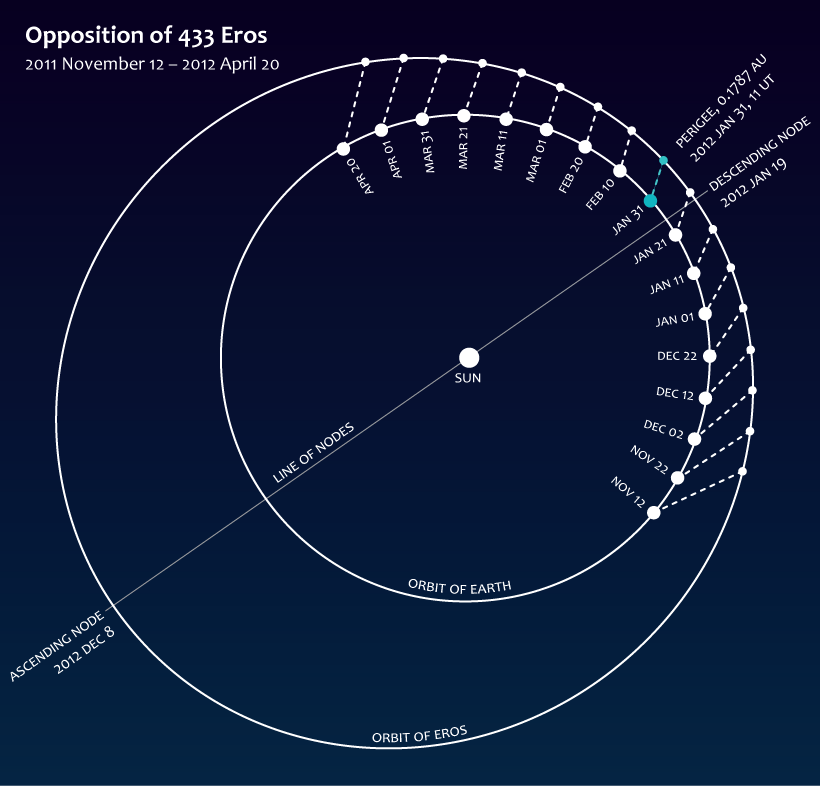

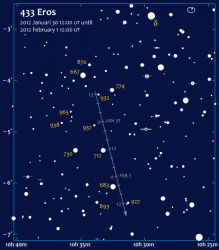

Scopes like the Faulkes Telescope North, even though it has a huge 2m (almost the same size as the one on the Hubble Space Telescope) mirror, is configured for smaller fields of view, literally only around 10 arcminutes, which will nicely fit in objects like Messier 51, the Whirpool Galaxy, but would take many separate images to image something like the full Moon (If Faulkes North were set up for that, which it’s not). It’s advantage is aperture size and immense CCD sensitivity. Typically our team using them is able to image a magnitude +23 moving object (comet or asteroid) in under a minute using a red filter too!

A field of view with a scope like the twin Faulkes scopes, which are owned and operated byLCOGT is perfect for smaller deep sky objects and my own interests which are comets and asteroids.Many other research projects such as exoplanets and the study of variable stars are conducted using these telescopes.Many schools start out imaging nebulae, smaller galaxies and globular clusters, with our aim at the Faulkes Telescope Project office, to quickly get students moving on to more science based work, whilst keeping it fun. For imagers, mosaic approaches are possible to create larger fields, but this obviously will take up more imaging and telescope slew time.

Each robotic system has its own set of learning curves, and each can suffer from technical or weather related difficulties, like any complex piece of machinery or electronic system. Knowing a bit about the imaging process to begin with, sitting in on other’s observing sessions on things like Slooh, all helps. Also make sure you know your target field of view/size on the sky (usually in either right ascension and declination) or some systems have a “guided tour mode” with named objects, and make sure you can be ready to move the scope to it as quickly as possible, to get imaging. With the commercial robotic scopes, time really is money.

Magazines like Astronomy Now in the UK, as well as Astronomy and Sky and Telescope in the United States and Australia are excellent resources for finding out more, as they regularly feature robotic imaging and scopes in their articles. Online forums like cloudynights.com and stargazerslounge.com also have thousands of active members, many of whom regularly use robotic scopes and can give advice on imaging and use, and there are dedicated groups for robotic astronomy like the Online Astronomical Society. Search engines will also give useful information on what is available as well.

To get access to them, most of the robotic scopes require a simple sign up process, and then the user can either have limited free access, which is usually an introductory offer, or just start to pay for time. The scopes come in various sizes and quality of camera, the better they are, usually the more you pay. For education and school users as well as astronomical societies, The Faulkes Telescope (for schools) and the Bradford Robotic scope both offer free access, as does the NASA funded Micro Observatory project. Commercial ones like iTelescope, Slooh and Lightbuckets provide a range of telescopes and imaging options, with a wide variety of price models from casual to research grade instrumentation and facilities.

So what about my own use of Robotic Telescopes?

Personally I use mainly the Faulkes North and South scopes, as well as the Liverpool La Palma Telescope. I have worked with the Faulkes Telescope Project team now for a few years, and it’s a real honour to have such access to research grade intrumentation. Our team also use the iTelescope network when objects are difficult to obtain using the Faulkes or Liverpool scopes, though with smaller apertures, we’re more limited in our target choice when it comes to very faint asteroid or comet type objects.

After having been invited to meetings in an advisory capacity for Faulkes, late in 2011 I was appointed pro am program manager, co-ordinating projects with amateurs and other research groups. With regards to public outreach I have presented my work at conferences and public outreach events for Faulkes and we’re about to embark on a new and exciting project with the European Space Agency whom I work for also as a science writer.

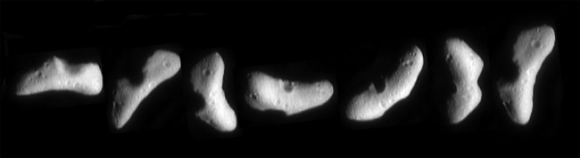

My use of Faulkes and the Liverpool scopes is primarily for comet recovery, measurement (dust/coma photometry and embarking on spectroscopy) and detection work, those icy solar system interlopers being my key interest. In this area, I co-discovered Comet C2007/Q3 splitting in 2010, and worked closely with the amateur observing program managed by NASA for comet 103P, where my images were featured in National Geographic, The Times, BBC Television and also used by NASA at their press conference for the 103P pre-encounter event at JPL.

The 2m mirrors have huge light grasp, and can reach very faint magnitudes in very little time. When attempting to find new comets or recover orbits on existing ones, being able to image a moving target at magnitude 23 in under 30s is a real boon. I am also fortunate to work alongside two exceptional people in Italy, Giovanni Sostero and Ernesto Guido, and we maintain a blog of our work, and I am a part of the CARA research group working on comet coma and dust measurements, with our work in professional research papers such as the Astrophysical Journal Letters and Icarus.

The Imaging Process

When taking the image itself, the process starts really before you have access to the scope. Knowing the field of view, what it is you want to achieve is critical, as is knowing the capabilities of the scope and camera in question, and importantly, whether or not the object you want to image is visible from the location/time you’ll be using it.

First thing I would do if starting out again is look through the archives of the telescope, which are usually freely available, and see what others have imaged, how they have imaged in terms of filters, exposure times etc, and then match that against your own targets.

Ideally, given that in many cases, time will be costly, make sure that if you’re aiming for a faint deep sky object with tenuous nebulosity, you don’t pick a night with a bright Moon in the sky, even with narrowband filters, this can hamper the final image quality, and that your choice of scope/camera will in fact image what you want it to. Remember that others may also want to use the same telescopes, so plan ahead and book early. When the Moon is bright, many of the commercial robotic scope vendors offer discounted rates, which is great if you’re imaging something like globular clusters maybe, which aren’t as affected by the moonlight (as say a nebula would be)

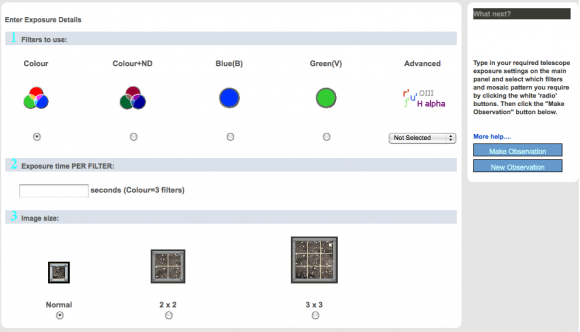

Forward planning is usually essential, knowing that your object is visible and not too close to any horizon limits which the scope may impose, ideally picking objects as high up as possible, or rising to give you plenty of imaging time. Once that’s all done, then following the scope’s imaging process depends on which one you choose, but with something like Faulkes, it’s as simple as selecting the target/FOV, slewing the scope, setting the filter, and then exposure time and then waiting for the image to come in.

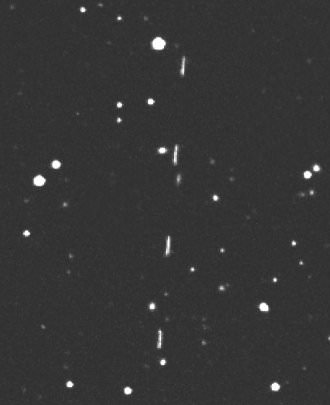

The number of shots taken depends on the time you have. Usually when imaging a comet using Faulkes I will try to take between 10 and 15 images to detect the motion, and give me enough good signal for the scientific data reduction which follows. Always remember though, that you’re usually working with vastly superior equipment than you have at home, and the time it takes to image an object using your home setup will be a lot less with a 2m telescope. A good example is that a full colour high resolution image of something like the Eagle Nebula can be obtained in a matter of minutes on Faulkes, in narrowband, something which would usually take hours on a typical backyard telescope.

For imaging a non moving target, the more shots in full colour or with your chosen filter (Hydrogen Alpha being a commonly used one with Faulkes for nebula) you can get the better. When imaging in colour, the three filters on the telescope itself are grouped into an RGB set, so you don’t need to set up each colour band. I’d usually add a luminance layer with H-Alpha if it’s an emission nebula, or maybe a few more red images if it’s not for luminance. Once the imaging run is complete, the data is usually placed on a server for you to collect, and then after downloading the FITS files, combine the images using Maxim (or other suitable software) and then on in to something like Photoshop to make the final colour image. The more images you take, the better the quality of the signal against the background noise, and hence a smoother and more polished final shot.

Between shots the only thing that will usually change will be filters, unless tracking a moving target, and possibly the exposure time, as some filters take less time to get the requisite amount of light. For example with a H-Alpha/OIII/SII image, you typically image for a lot longer with SII as the emission with many objects is weaker in this band, whereas many deep sky nebula emit strongly in the H-Alpha.

The Image Itself

As with any imaging of deep sky objects, don’t be afraid to throw away poor quality sub frames (the shorter exposures which go to make up the final long exposure when stacked). These could be affected by cloud, satellite trails or any number of factors, such as the autoguider on the telescope not working correctly. Keep the good shots, and use those to get as good a RAW stacked data frame as you can. Then it’s all down to post processing tools in products like Maxim/Photoshop/Gimp, where you’d adjust the colours, levels, curves and possibly use plug ins to sharpen up the focus, or reduce noise. If it’s pure science your interested in, you’ll probably skip most of those steps and just want good, calibrated image data (dark and flat field subtracted as well as bias)

The processing side is very important when taking shots for aesthetic value, it seems obvious, but many people can overdo it with image processing, lessening the impact and/or value of the original data. Usually most amateur imagers spend more time on processing than actual imaging, but this does vary, it can be from hours to literally days doing tweaks. Typically when processing an image taken robotically, the dark and flat field calibration are done. First thing I do is access the datasets as FITS files, and bring those in to Maxim DL. Here I will combine and adjust the histogram on the image, possible running multiple iterations of a de-convolution algorithm if the start points are not as tight (maybe due to seeing issues that night).

Once the images are tightened up and then stretched, I will save them out as FITS files, and using the free FITS Liberator application bring them in to Photoshop. Here, additional noise reduction and contrast/level and curve adjustments will be made on each channel, running a set of actions known as Noels actions (a suite of superb actions by Noel Carboni, one of the worlds foremost imaging experts) can also enhance the final individual red green and blue channels (and the combined colour one).

Then, I will composite the images using layers into a colour final shot, adjusting this for colour balance and contrast. Possibly running a focus enhancement plug in and further noise reduction. Then publish them via flickr/facebook/twitter and/or submit to magazines/journals or scientific research papers depending on the final aim/goals.

Serendipity can be a wonderful thing

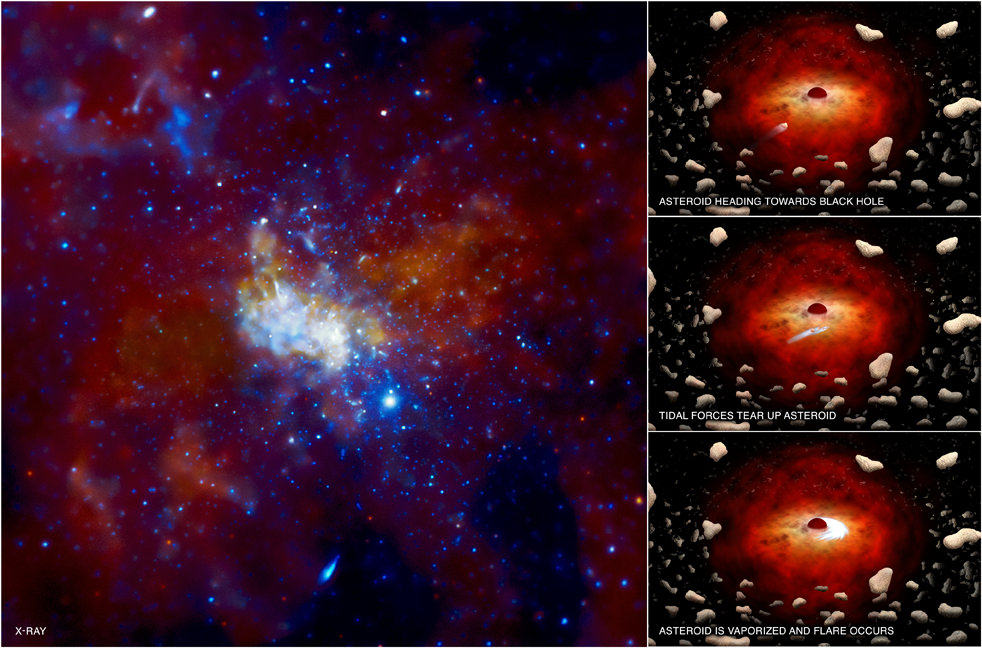

I got in to this quite by accident myself…. In March 2010, I had seen a posting on a newsgroup that Comet C/2007 Q3, a magnitude 12-14 object at the time, was passing near to a galaxy, and would make an interesting wide field side by side shot. That weekend, using my own observatory, I imaged the comet over several nights, and noticed a distinct change in the tail and brightness of the comet over two nights in particular.

A member of the BAA (British Astronomical Association), seeing my images, then asked if I would submit them for publication. I decided however to investigate this brightening a bit further, and as I had access to the Faulkes that week, decided to point the 2m scope at this comet, to see if anything unusual was taking place. The first images came in, and I immediately, after loading them in to Maxim DL and adjusting the histogram, noticed that a small fuzzy blob appeared to be tracking the comet’s movement just behind it. I measured the separation as only a few arc-seconds, and after staring at it for a few minutes, decided that it may have fragmented.

I contacted Faulkes Telescope control, who put me in touch with the BAA comet section director, who kindly logged this observation the same day. I then contacted Astronomy Now magazine, who leapt on the story and images and immediately went to press with it on their website. The following days the media furore was quite literally incredible.

Interviews with national newspapers, BBC Radio, Coverage on the BBC’s Sky at Night television show, Discovery Channel, Radio Hawaii, Ethiopia were just a few of the news/media outlets that picked up the story.. the news went global that an amateur had made a major astronomical discovery from his desk using a robotic scope. This then led on to me working with members of the AOP project with the NASA/University of Maryland EPOXI mission team on imaging and obtaining light curve data for comet 103P late in 2010, again which led to articles and images in National Geographic, The Times and even my images used by NASA in their press briefings, alongside images from the Hubble Space Telescope. Subscription requests to Faulkes Telescope Project as a result of my discoveries went up by hundreds of % from all over the world.

In summary

Robotic telescopes can be fun, they can lead to amazing things, this past year, a work experience student I was mentor for with the Faulkes Telescope Project, imaged several fields we’d assigned to her, where our team then found dozens of new and un-catalogued asteroids, and she also managed to image a comet fragmenting. Taking pretty pictures is fun, but the buzz for me comes with the real scientific research I am now engaged in, and it’s a pathway I aim to stay on probably for the rest of my astronomical lifetime. For students and people who don’t have the ability to either own a telescope due to financial or possibly location constraints, it’s a fantastic way to do real astronomy, using real equipment, and I hope, in reading this, you’re encouraged to give these fantastic robotic telescopes a try.