[/caption]

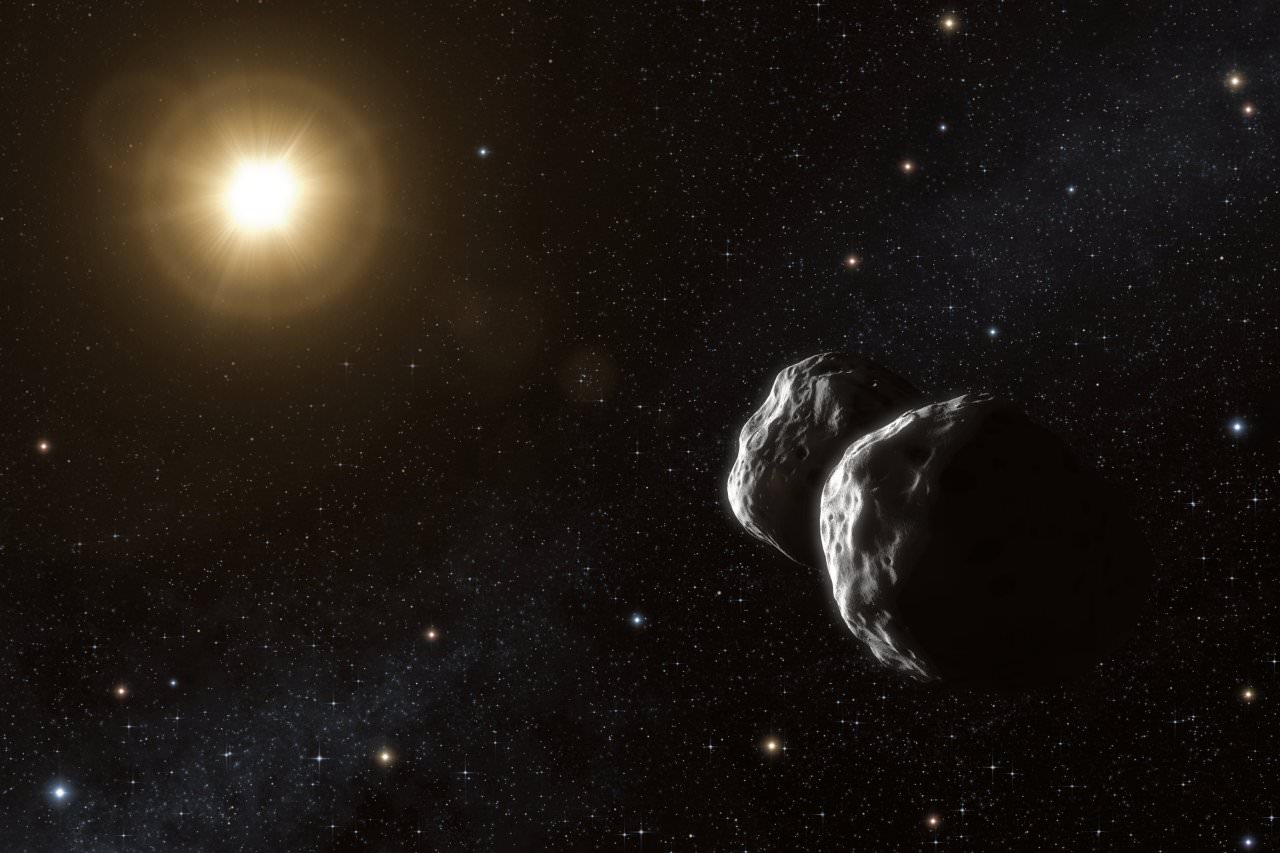

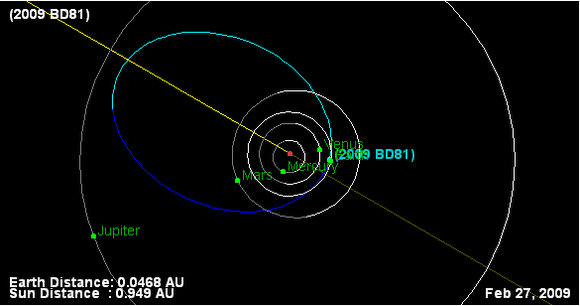

While observing a known asteroid on January 31, 2009, astronomer Robert Holmes from the Astronomical Research Institute near Charleston, Illinois found another high speed object moving nearby through the same field of view. The object has now been confirmed to be a previously undiscovered Potentially Hazardous Asteroid (PHA), with several possible Earth impact risks after 2042. This relatively small near-Earth asteroid, named 2009 BD81, will make its closest approach to Earth in 2009 on February 27, passing a comfortable 7 million kilometers away. In 2042, current projections have it passing within 5.5 Earth radii, (approximately 31,800 km or 19,800 miles) with an even closer approach in 2044 2046. Data from the NASA/JPL Risk web page show 2009 BD81 to be fairly small, with a diameter of 0.314 km (about 1000 ft.) Holmes, one of the world’s most prolific near Earth object (NEO) observers, said currently, the chance of this asteroid hitting Earth in 33 years or so is quite small; the odds are about 1 in 2 million, but follow-up observations are needed to provide precise calculations of the asteroid’s potential future orbital path.

Holmes operates his one-man observatory at ARI, as part of NASA’s Near Earth Observation program and the Killer Asteroid Project. He also produces images for educational and public outreach programs like the International Astronomical Search Collaboration (IASC), which is operated by Patrick Miller at Hardin-Simmons University in Texas, which gives students and teachers the opportunity to make observations and discoveries.

In just the past couple of years, Holmes has found 250 asteroids, 6 supernovae, and one comet (C/2008 N1 (Holmes). However, he said he would trade all of them for this single important NEO discovery.

“I was doing a follow up observation of asteroid 2008 EV5,” Holmes told Universe Today, “and there was another object moving right next to it, so it was a pretty easy observation, actually. But you just have to be in the right place at the right time. If I had looked a few hours later, it would have moved away and I wouldn’t have seen it.”

A few hours later, teacher S. Kirby, from Ranger High School in Texas, who was taking part in a training class on how to use the data that Holmes collects for making observations used Holmes’ data measuring 2008 EV5 and also found the new object. Shortly after that, a student K. Dankov from the Bulgarian Academy of Science, Bulgaria who is part of ARO education and public outreach also noticed the new asteroid. Holmes listed both observers as co-discovers as well as another astronomer who made confirmation follow-up observations of what is now 2009 BD81.

Holmes is a tireless observer. Last year alone he made 10,252 follow-up observations on previously discovered NEO’s, more than 2000 more than the second ranked observatory, according to the NEO Dynamics website, based in Pisa, Italy.

Holmes has two telescopes, a 24-inch and 32-inch.

He works night-after-night to provide real-time images for the IASC program, uploading his images constantly during the night to an FTP site, so students and teachers can access the data and make their own analysis and observations from them. IASC is a network of observatories from 13 countries all around the world.

Holmes is proud of the work he does for education, and proud of the students and teachers who participate.

“They do a great job,” he said. “A lot of the teachers are doing this entirely on their own, taking it upon themselves to create a hands-on research class in their schools.” Holmes said recently, two students that have been involved with IASC in high school decided to enter the astrophysics program in college.

“I feel like we are making a difference in science and education,” he said, “and it is exciting to feel like you’re making a contribution, not just following up NEO’s but in people’s lives.”

Holmes also owns some of the faintest observations of anyone in the world.

“My telescopes won’t go to 24th magnitude,” Holmes said, “but I’ve got several 23rd magnitudes.”

“Getting faint observations is one of the things NASA wants to achieve, so that’s one of the things I worked diligently on,” Holmes continued. The statistics on the site bear that out clearly, which shows graphs and comparisons of various observatories.

To what does Holmes attribute his success? “It’s obviously not the huge number nights we have in Illinois to work,” Holmes said. The East-Central region of Illinois is known for its cloudy winter weather, when we often have our poorest astronomical “seeing.”

“However, I work every single night if it’s clear, even if it’s a full moon,” he said. “Most observatories typically shut down three days on either side of a full moon. But I keep working right on through. I found that with the telescopes I work with, I’ve been able to get to the 22nd magnitude even on a full moon night. Last year, I got about 187 nights of observing, which is the same number as the big observatories in the Southwest, when you take off the number of cloudy nights the 6 nights a month they don’t’ work around full moons. Sometimes you just have to work harder, and work when others aren’t to be able to catch up. That’s how we are able to do it, by working every single chance we have.”

He works alone at the observatory, running the pair of telescopes, and doing programming on the fly. “I refresh the confirmation page of new discoveries every hour so I can chase down any new discovery anyone has found,” he said. “If I just pre-programmed everything I wouldn’t have a fraction of the observations I have each year. I’d miss way too many because some of the objects are moving so fast.”

Holmes said some objects are moving 5,000 arc-seconds an hour on objects that are really close to Earth. “I’ve seen them go a full hour of right ascension per day and that’s pretty quick. They can go across the sky in four or five days,” said Holmes. “And there have been some that have gone from virtually 50 degrees north to 50 degrees south in one night. That’s was a screaming fast object, and you can’t preprogram for something like that, you actually have to be running the telescope manually.”

2009 BD81 is listed as a “risk” object on the NASA/JPL website. This is the 1,015th PHA discovered to date.

“It ranks high as a NEO in general,” said Holmes, “although not in a super-high category as far as the Torino scale,” which categorizes the impact hazard of NEOs. “At this point it’s considered a virtual impactor and that is typically is as high of a rating that you get at this point.”

“Because it is a virtual impactor, it will remain on that webpage and ask for observations every single night until it is removed as a virtual impactor or becomes too faint to see,” said Holmes. “In the past year, we’ve removed 23 virtual hazardous objects, which means there have been enough observations that the orbit of that object is no longer considered a threat to our planet.”

Because of the small number of observations of of 2009 BD81, the current chance of it hitting Earth is small. “The odds are really small right now,” said Holmes, “however, the smaller your orbital arc is the wider the path is at that point is of potential impact. The longer the arc gets, the narrower the cone of opportunity of impact becomes, and once that cone is no longer pointing at earth in the future, it is removed as a possible impactor.”

Holmes said the excitement of this discovery has been exhilarating. “It’s been a lot of fun. The energy level gets pretty high when you have something like this show up,” he said. “It’s pretty rare, and this is the first time I’ve ever had a NEO discovery. I’ve had several hundred asteroids, and just since the beginning of the school year we have had about 40 asteroids that students and teachers have discovered in the program. So having this as a NEO is kind of a nice thing.”

Holmes said he’ll track 2009 BD81 as long as he possibly can.

More information on 2009 BD81.

Holmes previously was a commercial photographer who had over 4,500 photographs published worldwide in over 50 countries. “At first astronomy was just a hobby in the evening,” said Holmes. “I worked with schools, who used the data and made some discoveries of supernovae and asteroids. It came to a point where it was really hard to work all day as a photographer and work all night in astronomy getting data for students.” So, he chose astronomy over photography.

Holmes now works under a grant from NASA to use astrometry to follow-up new asteroid discoveries for the large sky surveys and help students look for new asteroid discoveries for educational outreach programs.

One would assume that as a former commercial photographer, Holmes would attempt to capture the beauty of the night sky in photographs, but that’s not the case.

“The only thing I’m really interesting in is the scientific and educational aspect of astronomy,” said Holmes. “I’ve never taken a single color, pretty picture of the sky in the half a million images I’ve taken of the sky. It’s always been for research or education.”

Holmes is considered a professional astronomer by the Minor Planet Center and International Astronomical Union because he is funded by NASA, so that means he wasn’t eligible to receive the Edgar Wilson award when he found a comet last year.

Because of Holmes outstanding astronomical work, he is also an adjunct faculty member in the physics department at Eastern Illinois University in Charleston, Illinois.