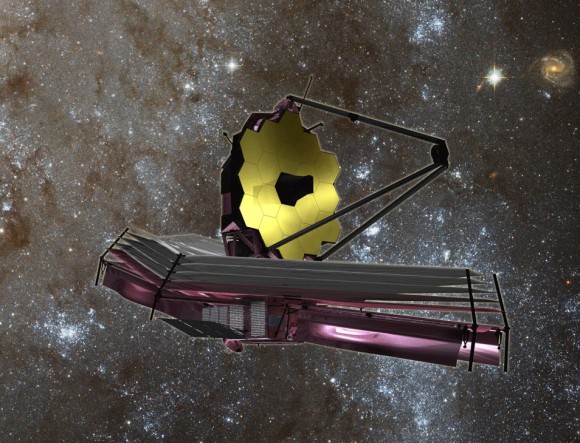

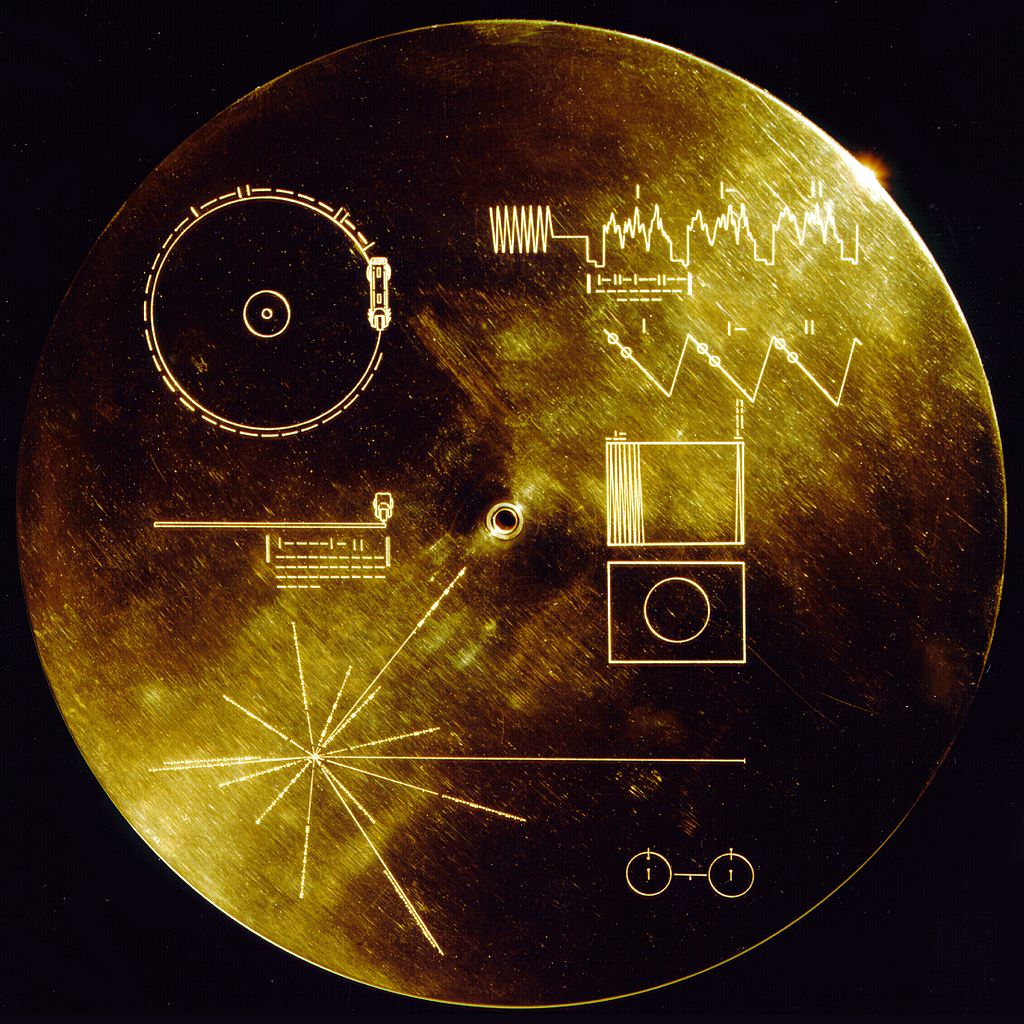

With robotic spacecraft, we have explored, discovered and expanded our understanding of the Solar System and the Universe at large. Our five senses have long since reached their limits and cannot reveal the presence of new objects or properties without the assistance of extraordinary sensors and optics. Data is returned and is transformed into a format that humans can interpret.

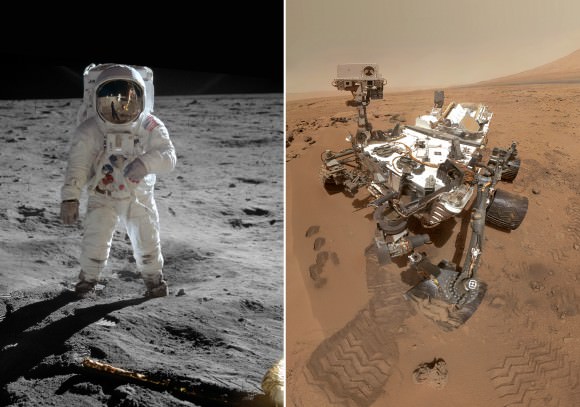

Humans remain confined to low-Earth orbit and forty-three years have passed since humans last escaped the bonds of Earth’s gravity. NASA’s budget is divided between human endeavors and robotic and each year there is a struggle to find balance between development of software and hardware to launch humans or carry robotic surrogates. Year after year, humans continue to advance robotic capabilities and artificial intelligence (A.I.), and with each passing year, it becomes less clear how we will fit ourselves into the future exploration of the Solar System and beyond.

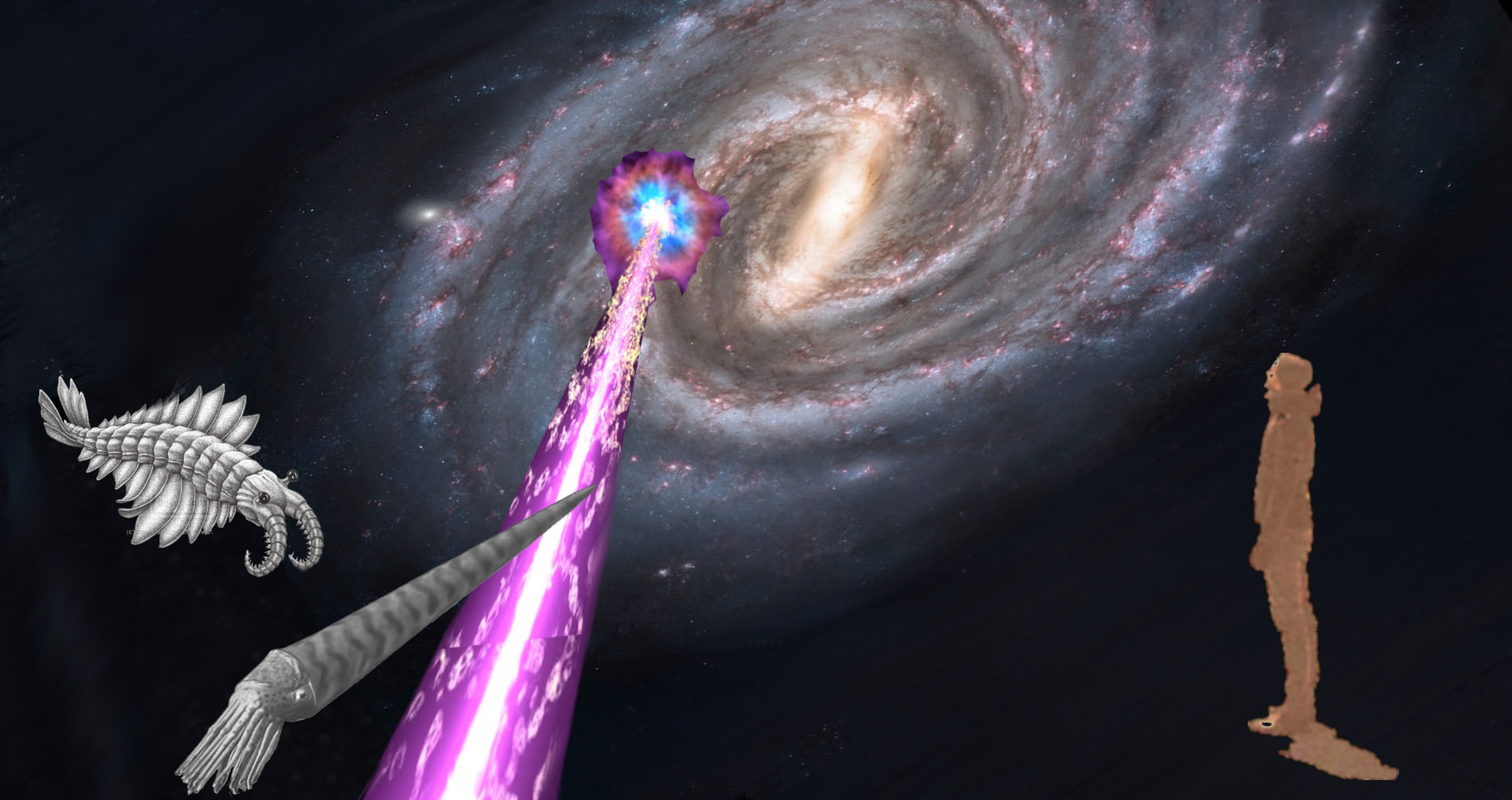

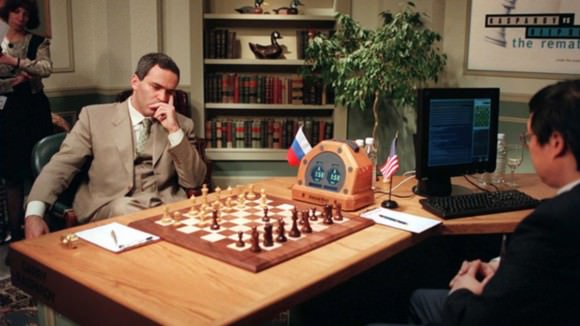

Is it a race in which we are unwittingly partaking that places us against our inventions? And like the aftermath of the Kasparov versus Deep Blue chess match, are we destined to accept a segregation as necessary? Allow robotics, with or without A.I., to do what they do best – explore space and other worlds?

Should we continue to find new ways and better ways to plug ourselves into our surrogates and appreciate with greater detail what they sense and touch? Consider how naturally our children engross themselves in games and virtual reality and how difficult it is to separate them from the technology. Or is this just a prelude and are we all antecedents of future Captain Kirks and Jean Luc Picards?

Approximately 55% of the NASA budget is in the realm of human spaceflight (HSF). This includes specific funds for Orion and SLS and half measures of supporting segments of the NASA agency, such as Cross-Agency Support, Construction and Maintenance. In contrast, appropriations for robotic missions – project development, operations, R&D – represent 39% of the budget.

The appropriation of funds has always favored human spaceflight, primarily because HSF requires costlier, heavier and more complex systems to maintain humans in the hostile environment of space. And while NASA budgets are not nearly weighted 2-to-1 in favor of human spaceflight, few would contest that the return on investment (ROI) is over 2-to-1 in favor of robotic driven exploration of space. And many would scoff at this ratio and counter that 3-to-1 or 4-to-1 is closer to the advantage robots have over humans.

Politics play a significantly bigger role in the choice of appropriations to HSF compared to robotic missions. The latter is distributed among smaller budget projects and operations and HSF has always involved large expensive programs lasting decades. The big programs attract the interest of public officials wanting to bring capital and jobs to their districts or states.

NASA appropriations are complicated further by a rift between the White House and Capitol Hill along party lines. The Democrat-controlled White House has favored robotics and the use of private enterprise to advance NASA while Republicans on the Hill have supported the big human spaceflight projects; further complications are due to political divisions over the issue of Climate Change. How the two parties treat NASA is the opposite to, at least, how the public perceives the party platforms – smaller government or more social programs, less spending and supporting private enterprise. This tug of war is clearly seen in the NASA budget pie chart.

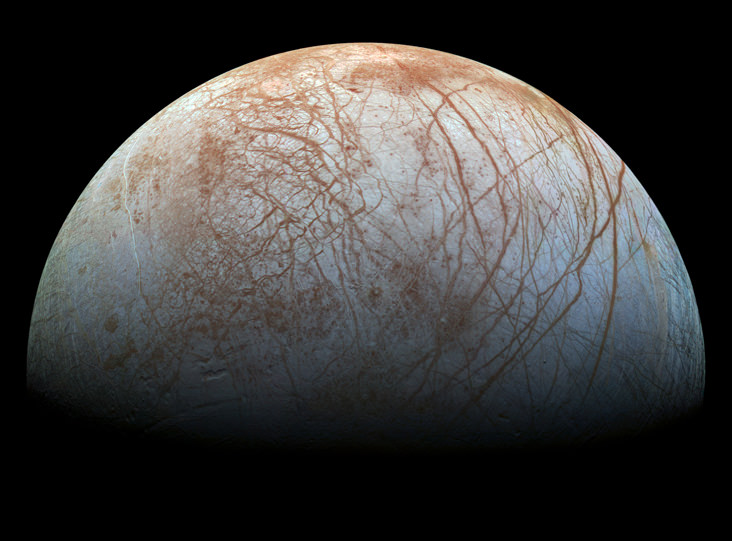

The House reduced the White House request for NASA Space Technology by 15% while increasing the funds for Orion and SLS by 16%. Space Technology represents funds that NASA would use to develop the Asteroid Redirect Mission (ARM), which the Obama administration favors as a foundation for the first use of SLS as part of a human mission to an asteroid. In contrast, the House appropriated $100 million to the Europa mission concept. Due to the delays of Orion and SLS development and anemic funding of ARM, the first use of SLS could be to send a probe to Europa.

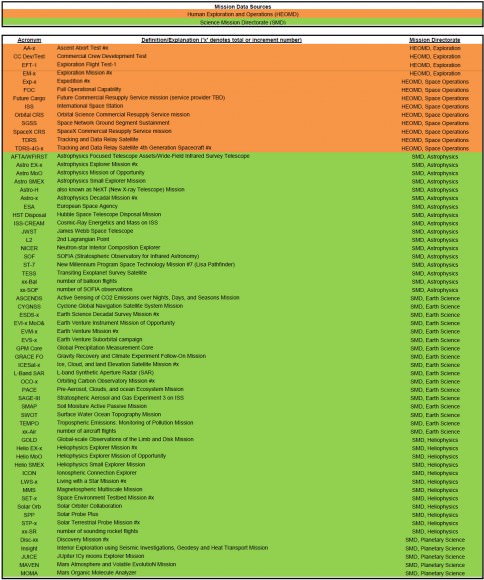

While HSF appropriations for Space Ops & Exploration (effectively HSF) increased ~6% – $300 million, NASA Science gained ~2% – $100 million over the 2014 appropriations; ultimately set by Capitol Hill legislators. The Planetary Society, which is the Science Mission Directorate’s (SMD) staunchest supporter, has expressed satisfaction that the Planetary Science budget has nearly reached their recommended $1.5 billion. However, the increase is delivered with the requirement that $100 million shall be used for Europa concept development and is also in contrast to cutbacks in other segments of the SMD budget.

Note also that NASA Education and Public Outreach (EPO) received a significant boost from Republican controlled Capital Hill. In addition to the specific funding – a 2% increase over 2014 and 34% over the White House request, there is $42 million given specifically to the Science Mission Directorate (SMD) for EPO. The Obama Adminstration has attempted to reduce NASA EPO in favor of a consolidated government approach to improve effectiveness and reduce government.

The drive to explore beyond Earth’s orbit and set foot on new worlds is not just a question of finances. In retrospect, it was not finances at all and our remaining shackles to Earth was a choice of vision. Today, politicians and administrators cannot proclaim ‘Let’s do it again! Let’s make a better Shuttle or a better Space Station.’ There is no choice but to go beyond Earth orbit, but where?

While the International Space Station program, led by NASA, now maintains a continued human presence in outer space, more people ask the question, ‘why aren’t we there yet?’ Why haven’t we stepped upon Mars or the Moon again, or anything other than Earth or floating in the void of low-Earth orbit. The answer now resides in museums and in the habitat orbiting the Earth every 90 minutes.

The retired Space Shuttle program and the International Space Station represent the funds expended on human spaceflight over the last 40 years, which is equivalent to the funds and the time necessary to send humans to Mars. Some would argue that the funds and time expended could have meant multiple human missions to Mars and maybe even a permanent presence. But the American human spaceflight program chose a less costly path, one more achievable – staying close to home.

Ultimately, the goal is Mars. Administrators at NASA and others have become comfortable with this proclamation. However, some would say that it is treated more as a resignation. Presidents have been defining the objectives of human spaceflight and then redefining them. The Moon, Lagrangian Points or asteroids as waypoints to eventually land humans on Mars. Partial plans and roadmaps have been constructed by NASA and now politicians have mandated a roadmap. And politicians forced continuation of development of a big rocket; one which needs a clear path to justify its cost to taxpayers. One does need a big rocket to get anywhere beyond low-Earth orbit. However, a cancellation of the Constellation program – to build the replacement for the Shuttle and a new human-rated spacecraft – has meant delays and even more cost overruns.

During the ten years that have transpired to replace the Space Shuttle, with at least five more years remaining, events beyond the control of NASA and the federal government have taken place. Private enterprise is developing several new approaches to lofting payloads to Earth orbit and beyond. More countries have taken on the challenge. Spearheading this activity, independent of NASA or Washington plans, has been Space Exploration Technologies Corporation (SpaceX).

SpaceX’s Falcon 9 and soon to be Falcon Heavy represent alternatives to what was originally envisioned in the Constellation program with Ares I and Ares V. Falcon Heavy will not have the capability of an Ares V but at roughly $100 million per flight versus $600 million per flight for what Ares V has become – the Space Launch System (SLS) – there are those that would argue that ‘time is up.’ NASA has taken too long and the cost of SLS is not justifiable now that private enterprise has developed something cheaper and done so faster. Is Falcon Nine and Heavy “better”, as in NASA administrator Dan Golden’s proclamation – ‘Faster, Better, Cheaper’? Is it better than SLS technology? Is it better simply because its cheaper for lifting each pound of payload? Is it better because it is arriving ready-to-use sooner than SLS?

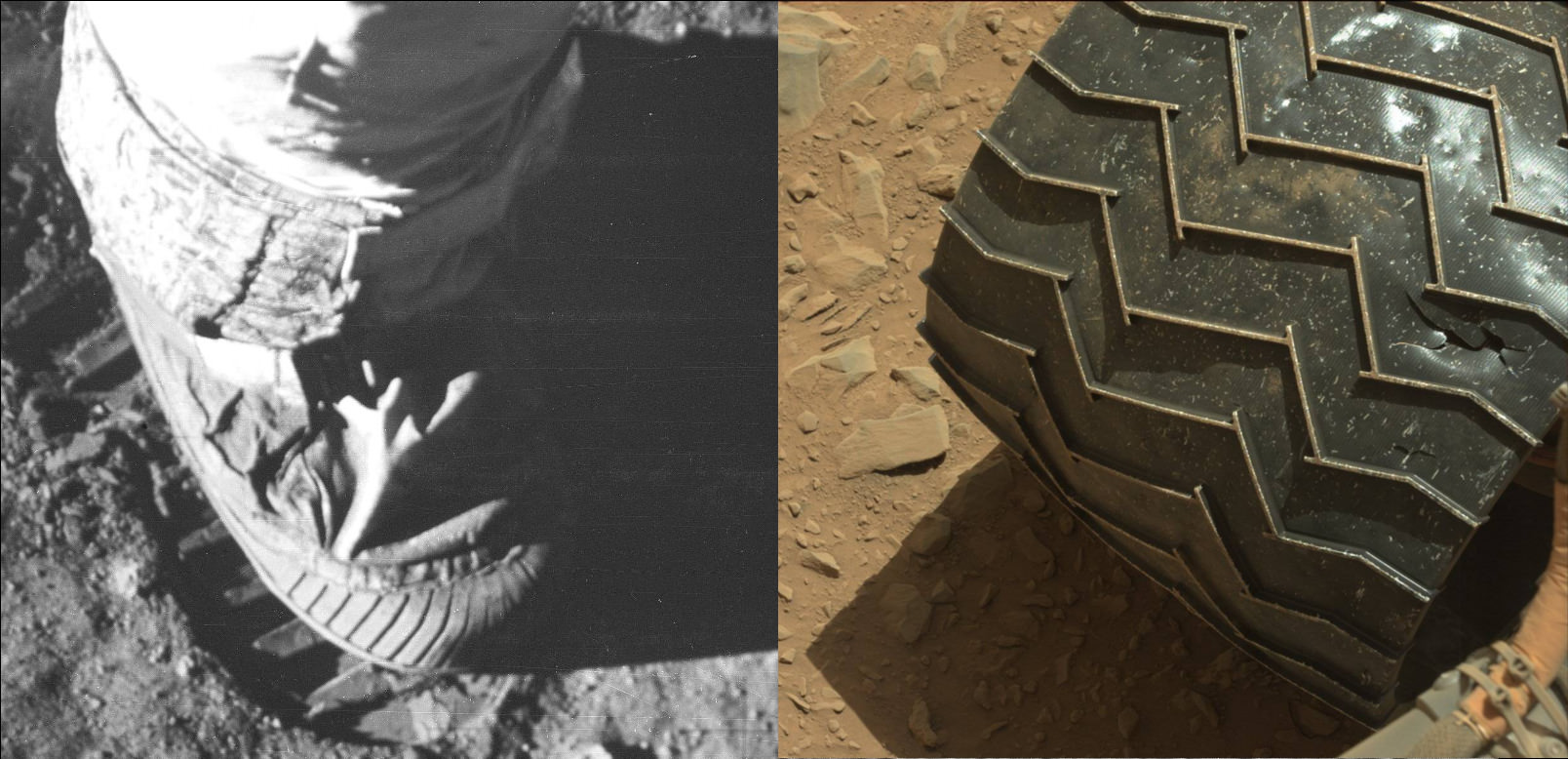

Humans will always depend on robotic launch vehicles, capsules and habitats laden with technological wonders to make our spaceflight possible. However, once we step out beyond Earth orbit and onto other worlds, what shall we do? From Carl Sagan to Steve Squyres, NASA scientists have stated that a trained astronaut could do in just weeks what the Mars rovers have required years to accomplish. How long will this hold up and is it really true?

Since Chess Champion Garry Kasparov was defeated by IBM’s Deep Blue, there have been 8 two-year periods representing the doubling of transistors in integrated circuits. This is a factor of 256. Arguably, computers have grown 100 times more powerful in the 17 years. However, robotics is not just electronics. It is the confluence of several technologies that have steadily developed over the 40 years that Shuttle technology stood still and at least 20 years that Space Station designs were locked into technological choices. Advances in material science, nano-technology, electro-optics, and software development are equally important.

While human decision making has been capable of spinning its wheels and then making poor choices and logistical errors, the development of robotics altogether is a juggernaut. While appropriations for human spaceflight have always surpassed robotics, advances in robotics have been driven by government investments across numerous agencies and by private enterprise. The noted futurist and inventor Ray Kurzweil who predicts the arrival of the Singularity by around 2045 (his arrival date is not exact) has emphasized that the surpassing of human intellect by machines is inevitable due to the “The Law of Accelerating Returns”. Technological development is a juggernaut.

In the same year that NASA was founded, 1958, the term Singularity was first used by mathematician John von Neumann to describe the arrival of artificial intelligence that surpasses humans.

Unknowingly, this is the foot race that NASA has been in since its creation. The mechanisms and electronics that facilitated landing men on the surface of the Moon never stopped advancing. And in that time span, human decisions and plans for NASA never stopped vacillating or stop locking existing technology into designs; suffering delays and cost overruns before launching humans to space.

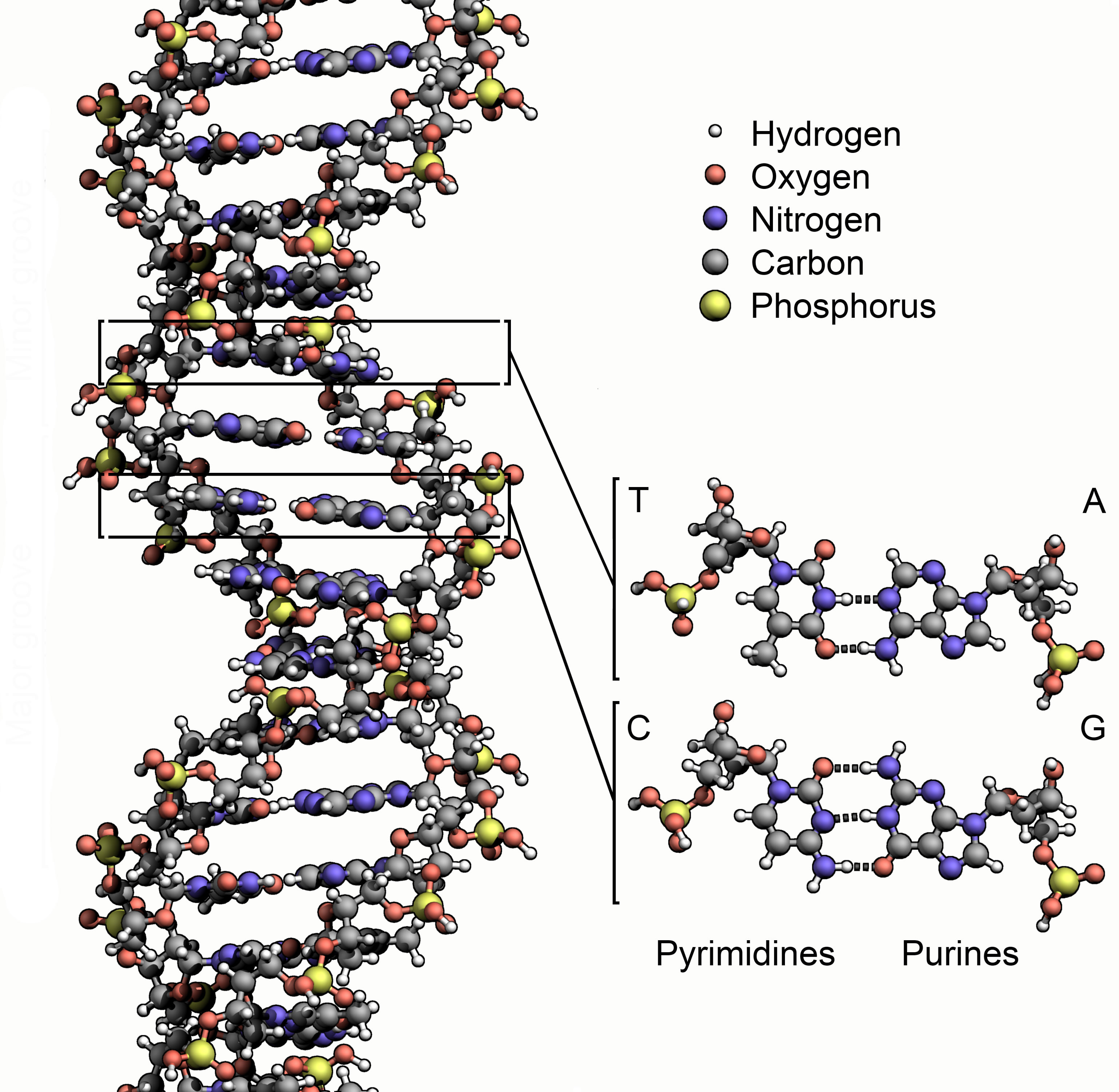

So are we destined to arrive on Mars and roam its surface like retired geologists and biologists wandering in the desert with a poking stick or rock hammer? Have we wasted too much time and has the window passed in which human exploration can make discoveries that robotics cannot accomplish faster, better and cheaper? Will Mars just become an art colony where humans can experience new sunrises and setting moons? Or will we segregate ourselves from our robotic surrogates and appreciate our limited skills and go forth into the Universe? Or will we mind meld with robotics and master our own biology just moments after taking our first feeble steps beyond the Earth?

The CROmnibus Is Here with Strong Funding for NASA & NSF (AAS)

NASA Gets Big Increase in FY2015 Omnibus, NOAA Satellites Do OK (SpacePolicyOnline.com)

Here’s How Planetary Science Will Spend Its $1.44 Billion in 2015 (Planetary Society)