[/caption]

Are we too hopeful in our hunt for extraterrestrial life? Regardless of exoplanet counts, super-Earths and Goldilocks zones, the probability of life elsewhere in the Universe is still a moot point — to date, we still only know of one instance of it. But even if life does exist somehow, somewhere besides Earth, would it really be all that alien?

In a recent paper titled “Bit by Bit: the Darwinian Basis for Life” Gerald Joyce, Professor of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, CA discusses the nature of life as we know it in regards to its fundamental chemical building blocks — DNA, RNA — and how its ability to pass on the memory of its construction separates true biology from mere chemistry.

“Evolution is nothing more than chemistry plus history,” Joyce said during a Public Library of Science podcast.

The DNA structures that evolved here on Earth — the only place in the Universe we know for certain that life can thrive — have proven to be highly successful (obviously). So what’s to say that life elsewhere wouldn’t be based on the same basic building blocks? And if it is, is it really a “new” life form?

“Truly new ‘alternative life’ would be life of a different biology,” Joyce said. “It would not have the information in it that is part of the same heritage of our life form.”

To arise in the first place, according to Joyce, new life can take two possible routes. Either it begins as chemical connections that grow increasingly more complex until they begin to hold on to the memory of their specific “bit” structure, eventually “bit-flipping” — aka, mutating — into new structures that are either successful or unsuccessful, or it starts from a more “privileged” beginning as an offshoot of previous life, bringing bits into a totally new, immediately successful orientation.

With those two scenarios, anywhere besides Earth “there are no example of either of those conditions so far.”

That’s not saying that there’s no life elsewhere in the Universe… just that we have yet to identify any evidence of it. And without evidence, any discussion of its probability is still pure conjecture.

“In order to estimate probabilities, we need facts,” said Joyce. “The problem is, there is only one life form. And so it’s not possible to estimate probability of life elsewhere when you have only one example.”

Even though exoplanets are being found on a nearly daily basis, and it’s only a matter of time before a rocky, Earthlike world with liquid water on its surface is confirmed orbiting another star, that’s no guarantee of the presence of alien life — despite what conclusions the headlines will surely jump to.

There could be a billion habitable planets in our galaxy. But what’s the relationship between habitable and inhabited?” Joyce asks. “We don’t know.”

Still, we will continue to search for life beyond our planet, be it truly alien in nature… or something slightly more familiar. Why?

“I think humans are lonely,” Joyce said. “I think humans are like Geppetto — we want to have a ‘real boy’ out there that we can point to, we want to find a Pinocchio living on some extrasolar planet… and then somehow we won’t be such a lonely life form.”

And who knows… if any aliens out there really are a lot like us, they may naturally be searching for evidence of our existence as well. If only to not be so lonely.

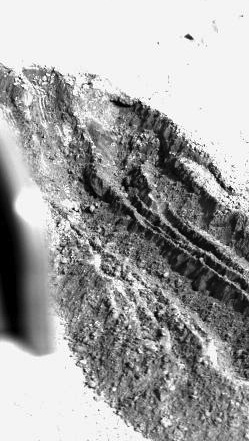

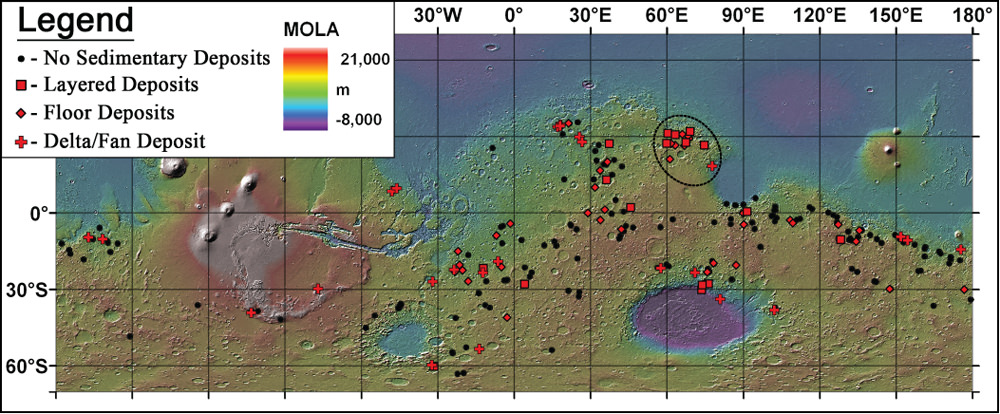

As it turns out, about a third of the lake beds examined still show evidence for clay deposits. A total of 79 lake beds out of 226 studied to be exact, indicating that they are less common on Mars than on Earth. The reason for this may be that the chemistry of the water was not ideal for preserving clays or that the lakes were relatively short-lived.

As it turns out, about a third of the lake beds examined still show evidence for clay deposits. A total of 79 lake beds out of 226 studied to be exact, indicating that they are less common on Mars than on Earth. The reason for this may be that the chemistry of the water was not ideal for preserving clays or that the lakes were relatively short-lived.