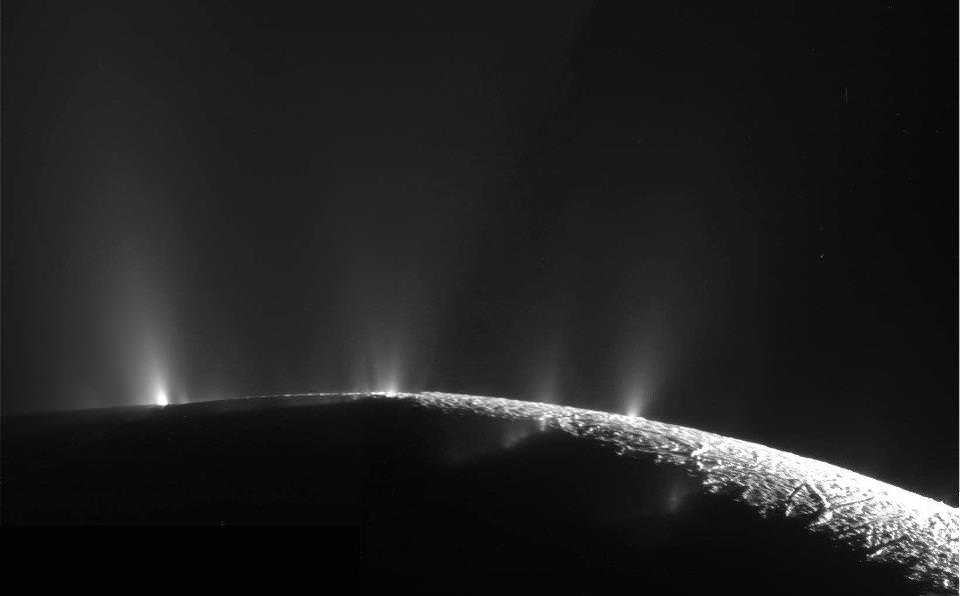

Along with Jupiter’s moon Europa, a tiny Saturnian moon, Enceladus, has become one of the most fascinating places in the solar system and a prime target in the search for extraterrestrial life. Its outward appearance is that of a small, frozen orb, but it revealed some surprises when the Cassini spacecraft gave us our first ever close-up look at this little world – huge geysers of water vapour spewing from its south pole. The implications were thought-provoking: Enceladus, like Europa, may have an ocean of liquid water below the surface. Unlike Europa however, the water is apparently able to make it up to the surface via fissures, erupting out into space as giant plumes.

Now, a new project sponsored by the German Aerospace Center, Enceladus Explorer, was launched on February 22, 2012, in an attempt to answer the question of whether there could be life on (or rather, inside) Enceladus. The project lays the groundwork for a new, ambitious mission being proposed for some time in the future.

Cassini was able to sample some of the plumes directly during its closest approaches to the moon, revealing that they contain water vapour, ice particles and organic molecules. If they originate from a reservoir of subsurface liquid water, as now thought by most scientists involved, it would indicate an environment which could be ideal for life to have started. The necessary ingredients for life (as we know it at least) are all there – water, heat and organic material. The fissures themselves generate much more heat relatively than the surrounding surface, suggesting that the conditions below the surface are much warmer. Maybe not “hot” per se, but warm enough, perhaps also with the aid of salts like in Earth’s oceans, to keep the water liquid.

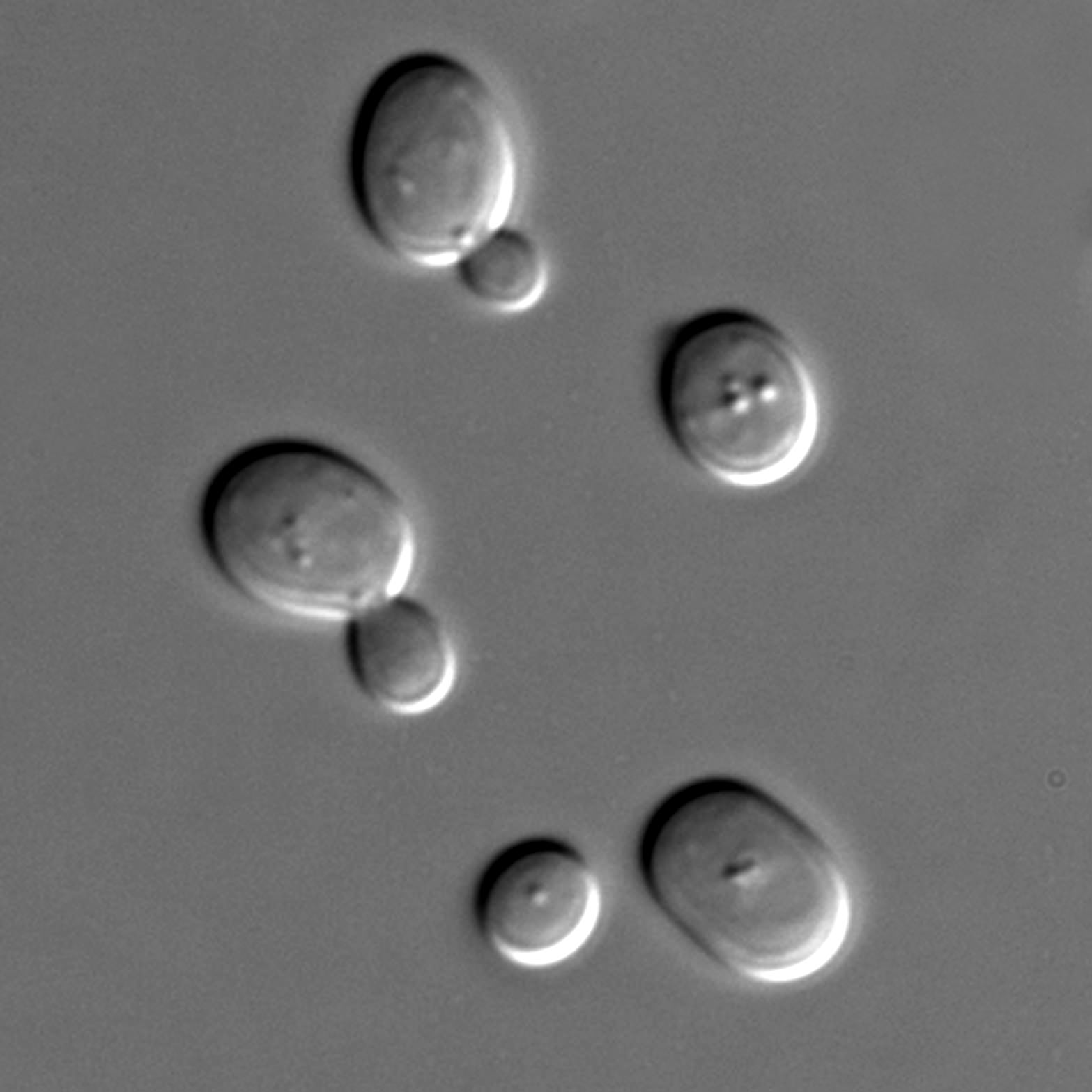

But what is the best way to search for evidence of life there? Follow-up missions have been proposed, to again sample the plumes, but with instruments able to look for life itself, which Cassini can’t do. This would seem ideal, as the water is being spewed out into space, with no drilling through the ice necessary. But the Enceladus Explorer project is proposing to do just that; the rationale is that any organisms (most likely microscopic) which may be in the water could easily be destroyed by the force of the ejection from the fissure. So then what is the best way to sample the water itself down below?

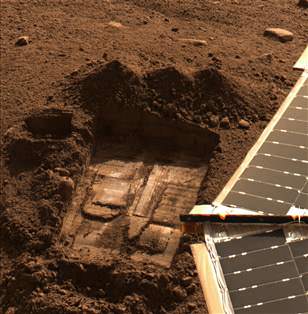

Enceladus Explorer would place a base station on the surface near one of the fissures; an ice drilling probe, the IceMole, would then melt its way through the ice crust to a depth of 100-200 metres until it reaches a liquid water reservoir. It would obtain samples of the water and examine them in situ for any traces of microorganisms. With no GPS system available, or external reference points to use, the probe would need to function autonomously, finding its own way through the ice to the water below.

The IceMole is already being tested here on Earth, and has successfully melted its way through the ice of the Morteratsch glacier in Switzerland. The next experiment will have it navigate its way through ice in the Antarctic, sampling completely uncontaminated water from a subsurface lake below the ice, much like the conditions found on Enceladus.

There is no timeframe yet for such a mission, especially given current budgets, but the Enceladus Explorer project has already shown that it is certainly technologically feasible and would provide an incredible look at an environment in the outer solar system which is amazingly Earth-like yet utterly alien at the same time.