[/caption]

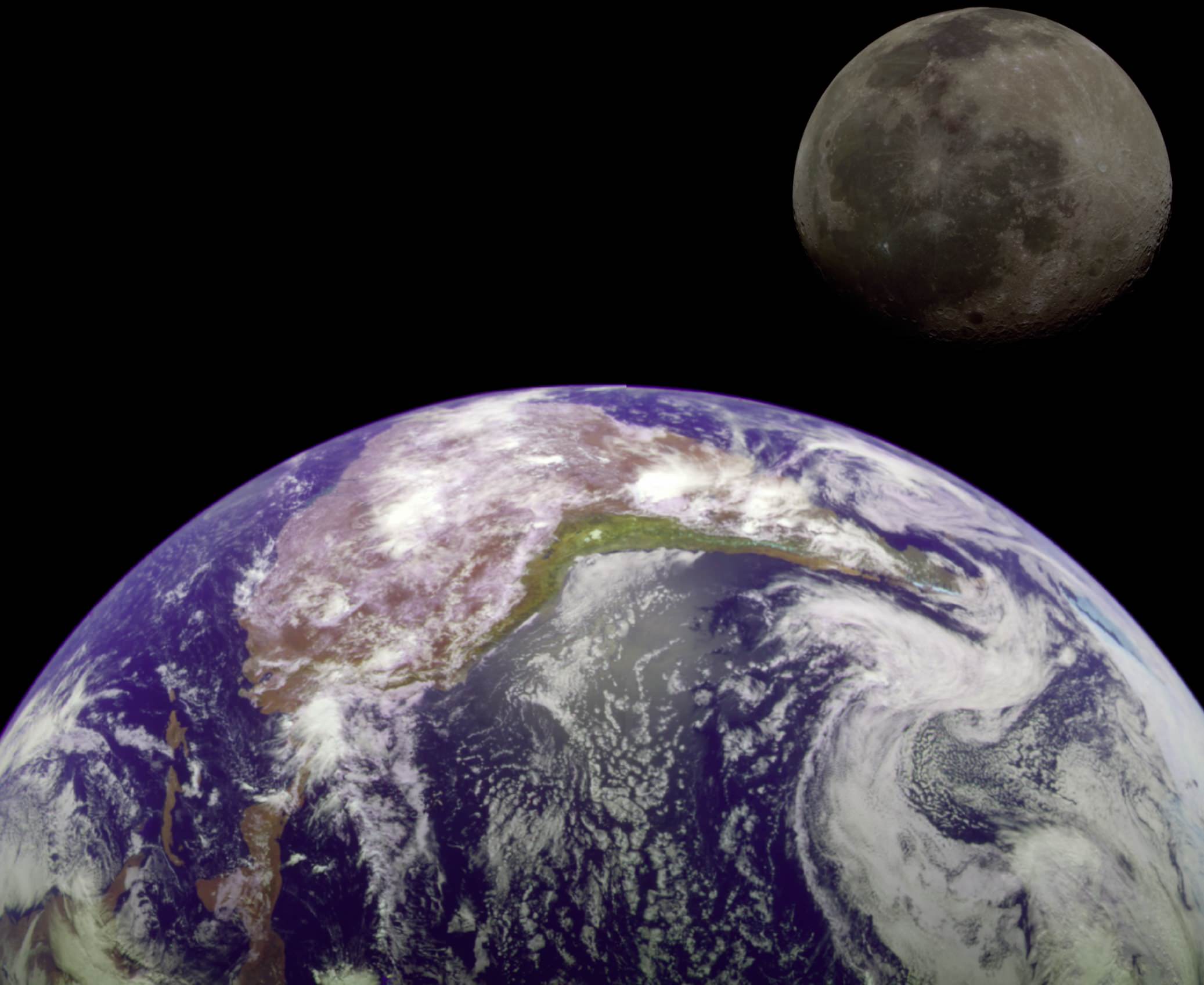

Ever since a study conducted back in 1993, it has been proposed that in order for a planet to support more complex life, it would be most advantageous for that planet to have a large moon orbiting it, much like the Earth’s moon. Our moon helps to stabilize the Earth’s rotational axis against perturbations caused by the gravitational influence of Jupiter. Without that stabilizing force, there would be huge climate fluctuations caused by the tilt of Earth’s axis swinging between about 0 and 85 degrees.

But now that belief is being called into question thanks to newer research, which may mean that the number of planets capable of supporting complex life could be even higher than previously thought.

Since planets with relatively large moons are thought to be fairly rare, that would mean most terrestrial-type planets like Earth would have either smaller moons or no moons at all, limiting their potential to support life. But if the new research results are right, the dependence on a large moon might not be as important after all. “There could be a lot more habitable worlds out there,” according to Jack Lissauer of NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California, who leads the research team.

Since planets with relatively large moons are thought to be fairly rare, that would mean most terrestrial-type planets like Earth would have either smaller moons or no moons at all, limiting their potential to support life. But if the new research results are right, the dependence on a large moon might not be as important after all. “There could be a lot more habitable worlds out there,” according to Jack Lissauer of NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California, who leads the research team.

It seems that the 1993 study did not take into account how fast the changes in tilt would occur; the impression given was that the axis fluctuations would be wild and chaotic. Lissauer and his team conducted a new experiment simulating a moonless Earth over a time period of 4 billion years. The results were surprising – the axis tilt of the Earth varied only between about 10 and 50 degrees, much less than the original study suggested. There were also long periods of time, up to 500 million years, when the tilt was only between 17 and 32 degrees, a lot more stable than previously thought possible.

So what does this mean for planets in other solar systems? According to Darren Williams of Pennsylvania State University, “Large moons are not required for a stable tilt and climate. In some circumstances, large moons can even be detrimental, depending on the arrangement of planets in a given system. Every system is going to be different.”

Apparently the assumption that a planet needs a large moon in order to be capable of supporting life was a bit premature. The results so far from the Kepler mission and other telescopes have shown that there is a wide variety of planets orbiting other stars, and so probably also moons, which we are now also on the verge of being able to detect. It’s nice to think that more of the terrestrial-type rocky planets, with or without moons, might be habitable after all.

The animated sequence to the left shows the water cycle of the Martian atmosphere in action:

The animated sequence to the left shows the water cycle of the Martian atmosphere in action: