[/caption]

Interested in helping NASA scientists pinpoint where to look for signs of life on Mars?

If so, you can join a new citizen science website called MAPPER, launched in conjunction with the Pavilion Lake Research Project’s 2011 field season.

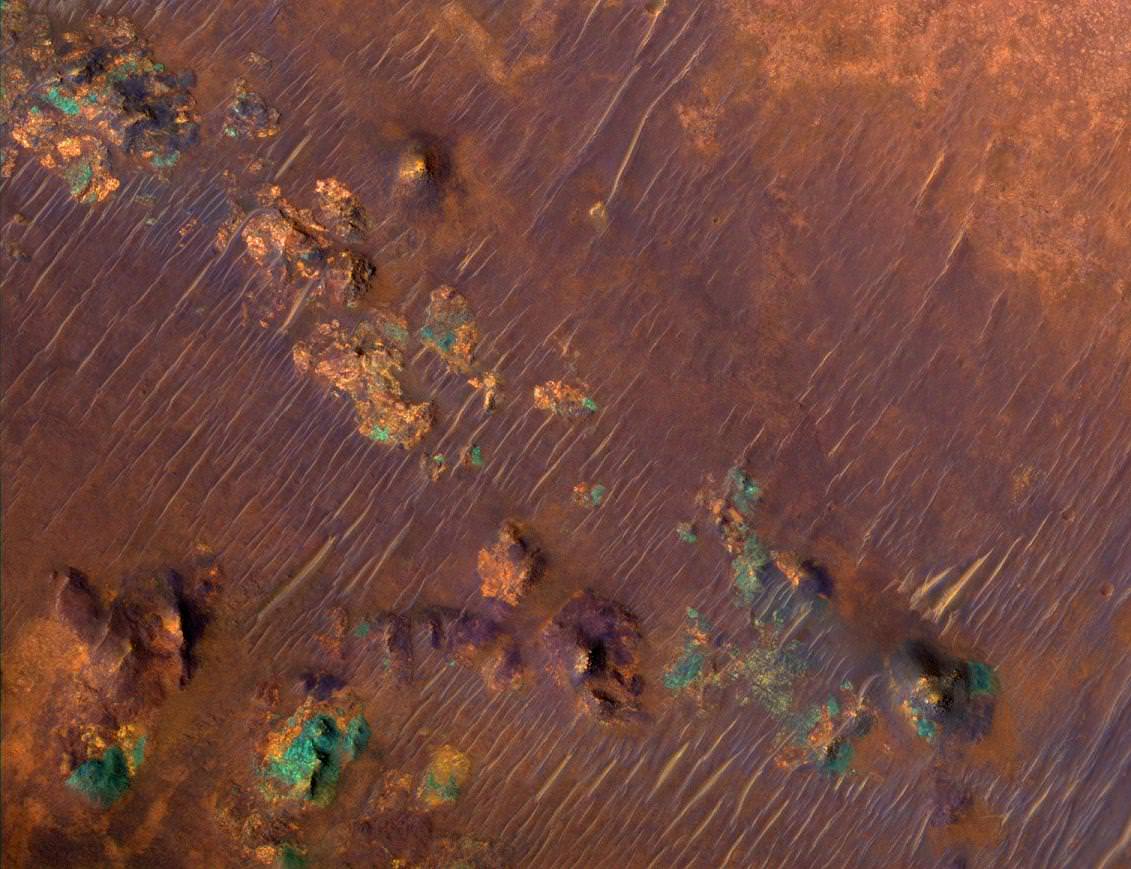

How can the MAPPER and Pavilion Lake Research projects help scientists look for off-Earth life?

Since 2008, the Pavilion Lake Research Project (PLRP) has used DeepWorker submersible vehicles to investigate the underwater environment of two lakes in Canada (Pavilion and Kelly). With the MAPPER project, citizen scientists can work with NASA scientists and explore the lake bottoms from the view of a DeepWorker pilot.

The PLRP team’s main area of focus are freshwater carbonate formations known as microbialites. By studying microbialites that thrive in Pavilion and Kelly Lake, the scientists believe a better understanding of how the formations develop. Through a greater understanding of the carbonate formations, the team believes they will gain deeper insights into where signs of life may be found on Mars and beyond.

To investigate the formations in detail, video footage and photos of the lake bottom are recorded by DeepWorker sub pilots. The data requires analysis in order to determine what types of features can be found in different parts of the lake. Analyzing the data allows the team to answer questions such as; “how does microbialite texture and size vary with depth?” and “why do microbialites grow in certain parts of the lake but not in others?”.

The amount of data to analyze is staggering – if each image taken were to be printed, the stack would be taller than the depth of Pavilion Lake (over 60 meters). If each image were reviewed one-by-one, the PLRP’s team would never be able to complete their work. Distributing the work to the general public solves the problem, due in part by spreading the massive work out over many volunteers across the Internet.

Since the PLRP 2011 field season Morphology Analysis Project for Participatory Exploration and Research (MAPPER) MAPPER has been open to the general public. By opening MAPPER to the public, anyone can explore Pavilion and Kelly Lake as full-fledged members of PLRP’s Remote Science Team.

So how do volunteers use MAPPER to help the PLRP team?

Once volunteers create an account at: getmapper.com, the volunteers complete a brief tutorial, which provides the necessary training to tag photos in the PLRP dataset. MAPPER has ease-of-use in mind, providing users with a simple interface, which makes tagging features like sediment, microbialites, rocks, and algae easy. In case a user is unsure of how to tag a photo, examples and descriptions of each feature are available.

In a manner similar to online games, each photo tagged earns the volunteer points which can be used to unlock new activities. Volunteers can also compete with other Remote Science Team members on the MAPPER leaderboard. Volunteers can also check to see how close each dataset is to being completely reviewed and see how much they have contributed to said dataset, as well as seeing what features have been tagged the most. Volunteers who tag a photo as ‘cool’ save said image to their Cool Photos album, allowing them to easily find the image at a later date.

PLRP Remote Science Team members from across North America, Europe and Asia have already been making discoveries in Pavilion and Kelly Lake. If you’d like to become a PLRP Remote Science Team member, visit: www.getmapper.com

You can also learn more by visiting the MAPPER Facebook page