[/caption]

Indian scientists flying a giant balloon experiment have announced the discovery of three new species of bacteria from the stratosphere.

In all, 12 bacterial and six fungal colonies were detected, nine of which, based on gene sequencing, showed greater than 98 percent similarity with reported known species on earth. Three bacterial colonies, however, represented totally new species. All three boast significantly higher UV resistance compared to their nearest phylogenetic neighbors on Earth.

The experiment was conducted using a balloon that measures 26.7 million cubic feet (756,059 cubic meters) carrying 1,000 pounds (459 kg) of scientific payload soaked in liquid Neon. It was flown from the National Balloon Facility in Hyderabad, operated by the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR).

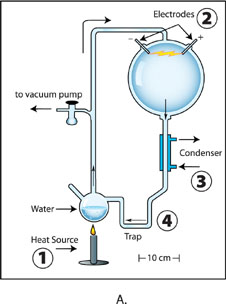

An onboard cryosampler contained sixteen evacuated and sterilized stainless steel probes. Throughout the flight, the probes remained immersed in liquid Neon to create a cryopump effect. The cylinders, after collecting air samples from different heights ranging from 20 km to 41 km (12 to 25 miles) above the Earth’s surface, were parachuted down and retrieved. The samples were analyzed by scientists at the Center for Cellular and Molecular Biology in Hyderabad as well as the National Center for Cell Science in Pune for independent confirmation.

One of the new species has been named as Janibacter hoylei, after the astrophysicist Fred Hoyle, the second as Bacillus isronensis recognizing the contribution of ISRO in the balloon experiments which led to its discovery, and the third as Bacillus aryabhata after India’s celebrated ancient astronomer Aryabhata (also the name of ISRO’s first satellite).

The researchers have pointed out in a press release that precautionary measures and controls operating in the experiment inspire confidence that the new species were picked up in the stratosphere.

“While the present study does not conclusively establish the extra-terrestrial origin of microorganisms, it does provide positive encouragement to continue the work in our quest to explore the origin of life,” they added.

This was the second such experiment conducted by ISRO, with the first one in 2001. Even though the first experiment had yielded positive results, the researchers decided to repeat the experiment while exercising extra care to ensure that it was totally free from any terrestrial contamination.

Source: Indian Space Research Organisation

Additional links: Center for Cellular and Molecular Biology, National Center for Cell Science, Tata Institute of Fundamental Research