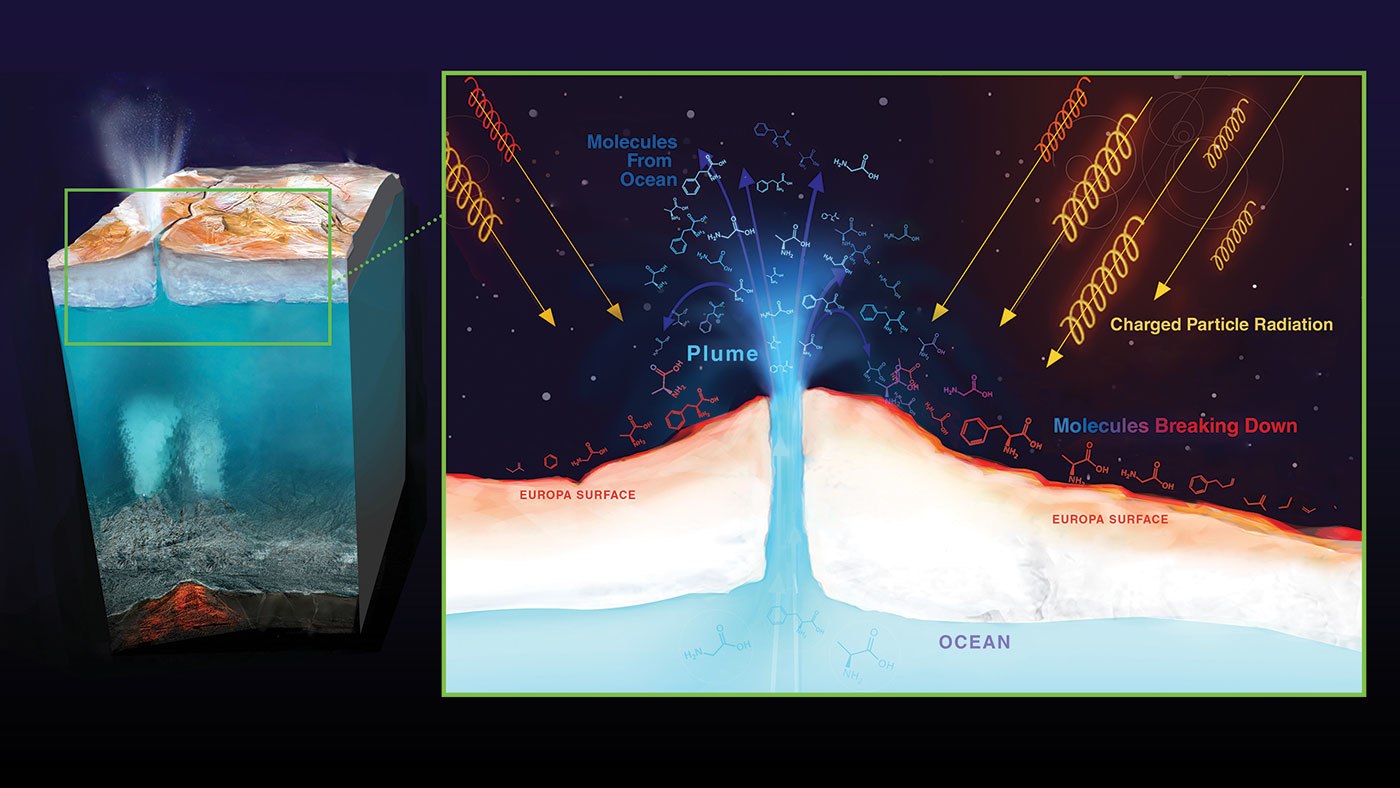

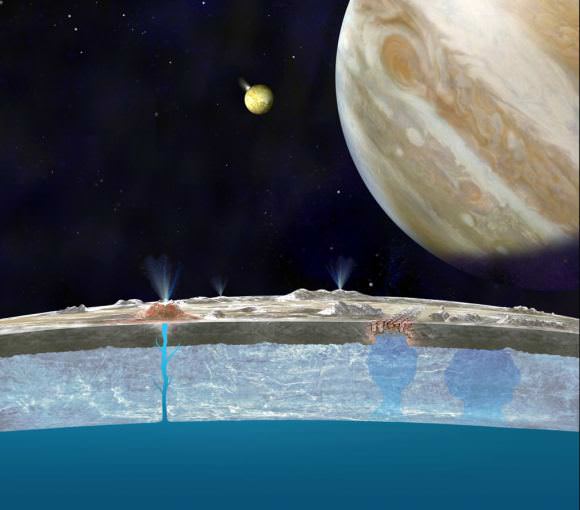

Ever since the Galileo probe provided compelling evidence for the existence of a global ocean beneath the surface of Europa in the 1990s, scientists have wondered when we might be able to send another mission to this icy moon and search for possible signs of life. Most of these mission concepts call for an orbiter or lander than will study Europa’s surface, searching the icy sheet for signs of biosignatures turned up from the interior.

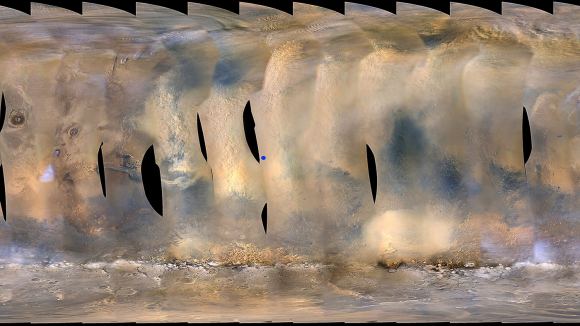

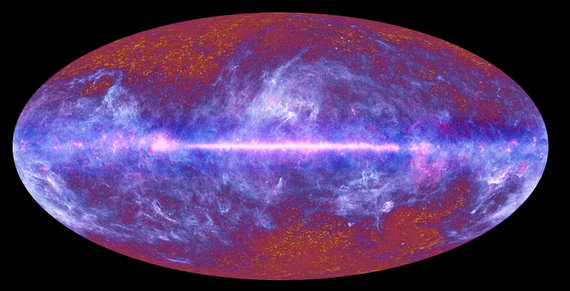

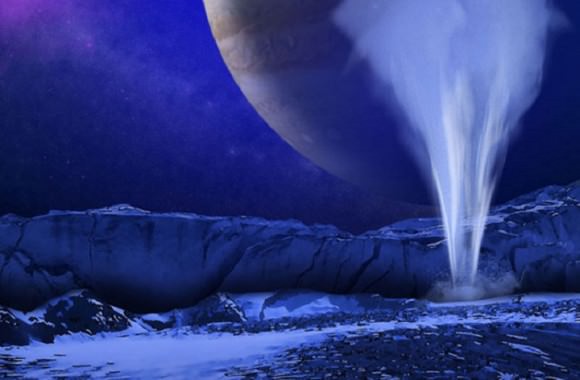

Unfortunately, Europa’s surface is constantly bombarded by radiation, which could alter or destroy material transported to the surface. Using data from the Galileo and Voyager 1 spacecraft, a team of scientists recently produced a map that shows how radiation varies across Europa’s surface. By following this map, future missions like NASA’s Europa Clipper will be able to find the spots where biosignatures are most likely to still exist.

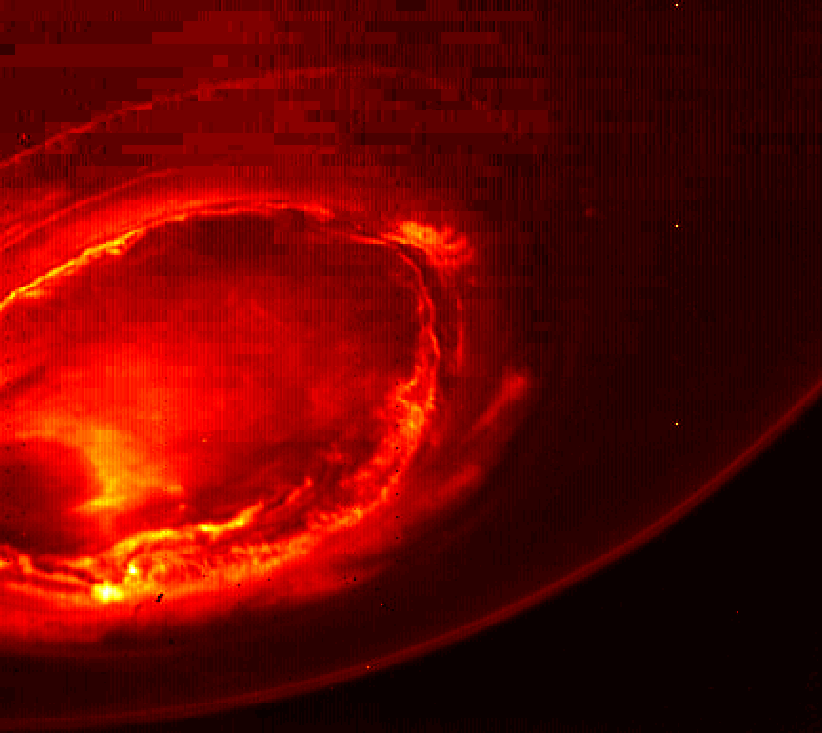

As many missions have revealed by studying Europa’s surface, the moon experiences periodic exchanges between the interior and the surface. If there is life in its interior ocean, then biological material could theoretically be brought to the surface where it could be studied. Since radiation from Jupiter’s magnetic field would destroy this material, knowing where it is most intense, how deep it goes, and how it could affect the interior are all important questions.

As Tom Nordheim, a research scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, explained in a recent NASA press release:

“If we want to understand what’s going on at the surface of Europa and how that links to the ocean underneath, we need to understand the radiation. When we examine materials that have come up from the subsurface, what are we looking at? Does this tell us what is in the ocean, or is this what happened to the materials after they have been radiated?”

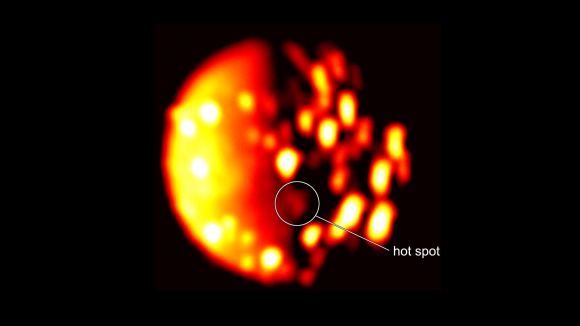

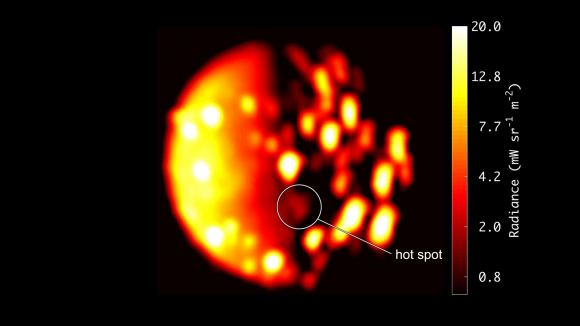

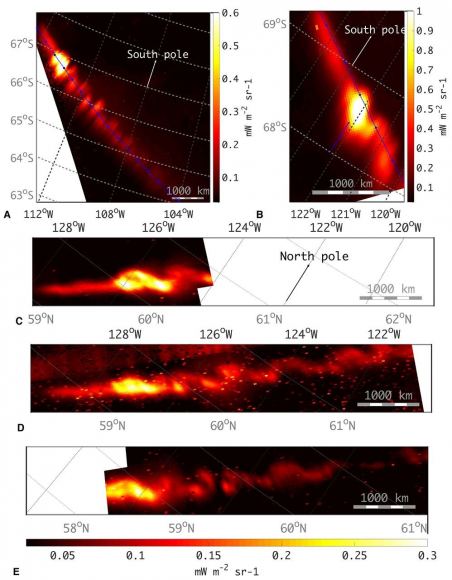

To address these question, Nordheim and his colleagues examined data from Galileo‘s flybys of Europa and electron measurements from NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft. After looking closely at the electrons blasting the moon’s surface, Nordheim and his team found that the radiation doses vary by location. The harshest radiation is concentrated in zones around the equator, and the radiation lessens closer to the poles.

The study which describes their findings recently appeared in the scientific journal Nature under the title “Preservation of potential biosignatures in the shallow subsurface of Europa“. The study was led by Nordheim and was co-authored by Kevin Hand (also with the JPL) and Chris Paranicas from the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland.

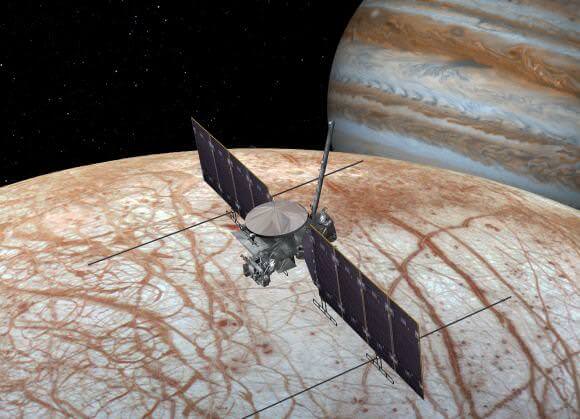

“This is the first prediction of radiation levels at each point on Europa’s surface and is important information for future Europa missions,” said Paranicas. Now that scientists know where to find regions least altered by radiation, they will be able to designate areas of study for the Europa Clipper, a JPL-led mission that is expected to launch as early as 2022.

For the sake of their study, Nordheim and his team went beyond a conventional two-dimensional map to build 3D models that examined how far below the surface the radiation penetrates. To test how deep organic material would have to be buried in order to survive, Nordheim and his team tested the effect of radiation on amino acids (the basic building blocks for proteins) to figure out how Europa’s exposure to radiation would affect potential biosignatures.

The results indicate how deep scientists will need to dig or drill during a potential future Europa lander mission in order to find any biosignatures that might be preserved. In the highest-radiation zones around the equator, the depth at which biosignatures could be found ranged from 10 to 20 cm (4 to 8 inches). At the middle- and high-latitudes, closer to the poles, the depths decrease to about 1 cm (0.4 inches). As Hand indicated:

“The radiation that bombards Europa’s surface leaves a fingerprint. If we know what that fingerprint looks like, we can better understand the nature of any organics and possible biosignatures that might be detected with future missions, be they spacecraft that fly by or land on Europa.”

When the Europa Clipper mission reaches the Jovian system, the spacecraft will orbit Jupiter and conducting about 45 close flybys of Europa. It’s advanced suite of scientific instruments will include cameras, spectrometers, plasma and radar instruments which will investigate the composition of the moon’s surface, its ocean, and material that has been ejected from the surface.

“Europa Clipper’s mission team is examining possible orbit paths, and proposed routes pass over many regions of Europa that experience lower levels of radiation,” Hand said. “That’s good news for looking at potentially fresh ocean material that has not been heavily modified by the fingerprint of radiation.”

With this new radiation map, the mission team will be able to narrow the range of possible research sites. This, in turn, will increase the likelihood that the orbiter mission will be able to settle the decades-old mystery of whether or not there is life in the Jovian system.