Astronomy can be a tricky business, owing to the sheer distances involved. Luckily, astronomers have developed a number of tools and strategies over the years that help them to study distant objects in greater detail. In addition to ground-based and space-based telescopes, there’s also the technique known as gravitational lensing, where the gravity of an intervening object is used to magnify light coming from a more distant object.

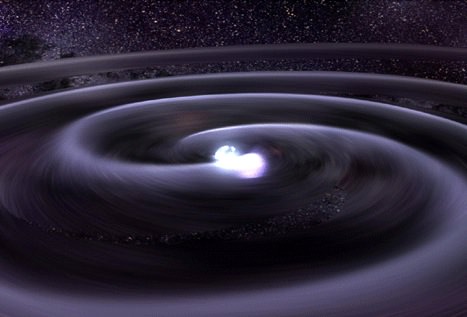

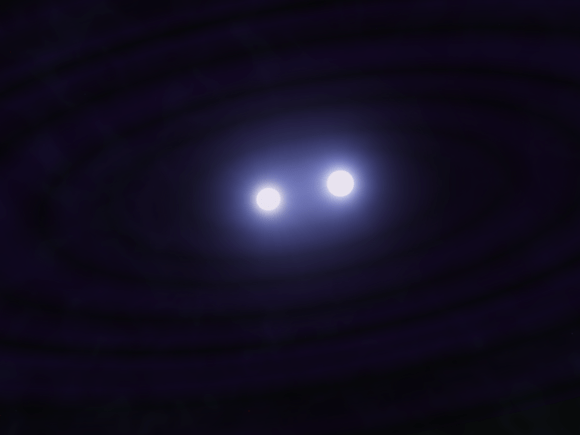

Recently, a team of Canadian astronomers used this technique to observe an eclipsing binary millisecond pulsar located about 6500 light years away. According to a study produced by the team, they observed two intense regions of radiation around one star (a brown dwarf) to conduct observations of the other star (a pulsar) – which happened to be the highest resolution observations in astronomical history.

The study, titled “Pulsar emission amplified and resolved by plasma lensing in an eclipsing binary“, recently appeared in the journal Nature. The study was led by Robert Main, a PhD astronomy student at the University of Toronto’s Dunlap Institute for Astronomy & Astrophysics, and included members from the Canadian Institute for Theoretical Astrophysics, the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, and the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research.

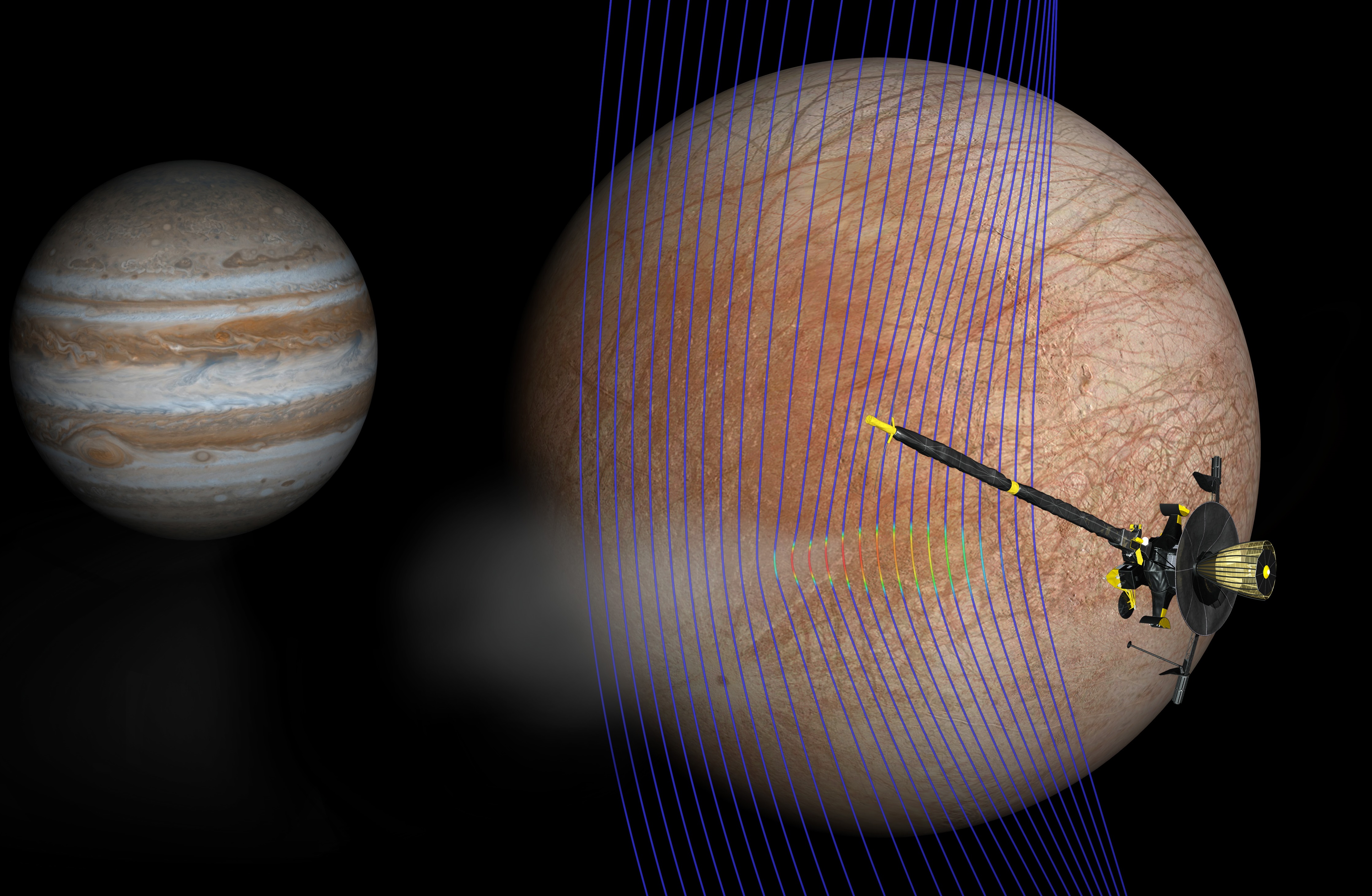

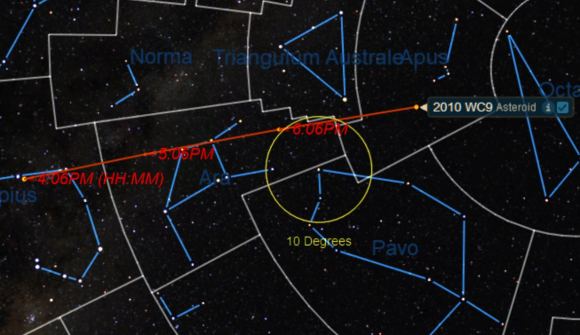

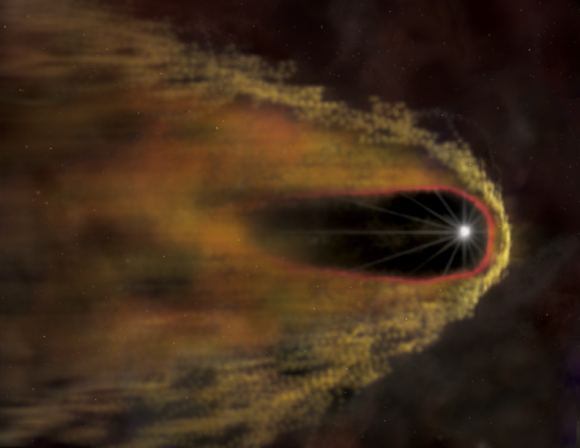

The system they observed is known as the “Black Widow Pulsar”, a binary system that consists of a brown dwarf and a millisecond pulsar orbiting closely to each other. Because of their close proximity to one another, scientists have determined that the pulsar is actively siphoning material from its brown dwarf companion and will eventually consume it. Discovered in 1988, the name “Black Widow” has since come to be applied to other similar binaries.

The observations made by the Canadian team were made possible thanks to the rare geometry and characteristics of the binary – specifically, the “wake” or comet-like tail of gas that extends from the brown dwarf to the pulsar. As Robert Main, the lead author of the paper, explained in a Dunlap Institute press release:

“The gas is acting like a magnifying glass right in front of the pulsar. We are essentially looking at the pulsar through a naturally occurring magnifier which periodically allows us to see the two regions separately.”

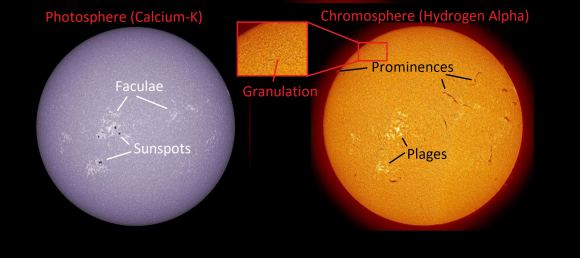

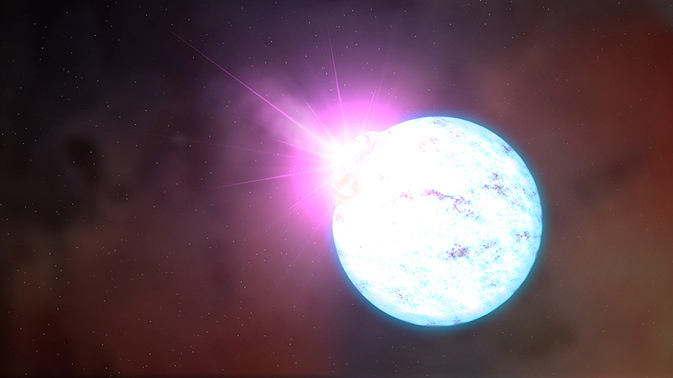

Like all pulsars, the “Black Widow” is a rapidly rotating neutron star that spins at a rate of over 600 times a second. As it spins, it emits beams of radiation from its two polar hotspots, which have a strobing effect when observed from a distance. The brown dwarf, meanwhile, is about one third the diameter of the Sun, is located roughly two million km from the pulsar and orbits it once every 9 hours.

Because they are so close together, the brown dwarf is tidally-locked to the pulsar and is blasted by strong radiation. This intense radiation heats one side of the relatively cool brown dwarf to temperatures of about 6000 °C (10,832 °F), the same temperature as our Sun. Because of the radiation and gases passing between them, the emissions coming from the pulsar interfere with each other, which makes them difficult to study.

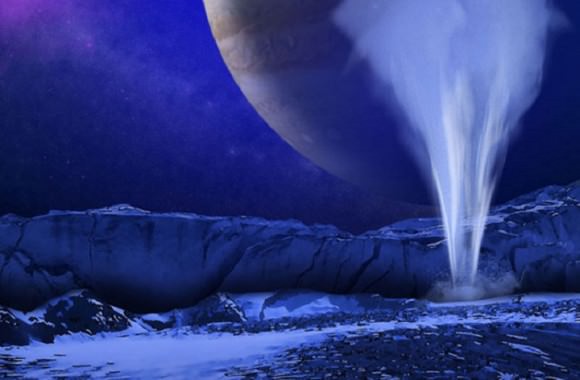

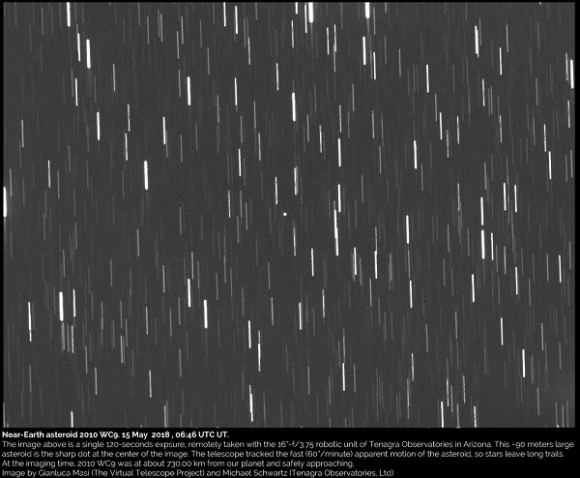

However, astronomers have long understood that these same regions could be used as “interstellar lenses” that could localize pulsar emission regions, thus allowing for their study. In the past, astronomers have only been able to resolve emission components marginally. But thanks to the efforts of Main and his colleagues, they were able observing two intense radiation flares located 20 kilometers apart.

In addition to being an unprecedentedly high-resolution observation, the results of this study could provide insight into the nature of the mysterious phenomena known as Fast Radio Bursts (FRBs). As Main explained:

“Many observed properties of FRBs could be explained if they are being amplified by plasma lenses. The properties of the amplified pulses we detected in our study show a remarkable similarity to the bursts from the repeating FRB, suggesting that the repeating FRB may be lensed by plasma in its host galaxy.”

It is an exciting time for astronomers, where improved instruments and methods are not only allowing for more accurate observations, but also providing data that could resolve long-standing mysteries. It seems that every few days, fascinating new discoveries are being made!

Further Reading: University of Toronto, Nature