Since the 1970s, astronomers have understood that a Supermassive Black Hole (SMBH) resides at the center of the Milky Way Galaxy. Located about 26,000 light-years from Earth between the Sagittarius and Scorpius constellations, this black hole has come to be known as Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*). Measuring 44 million km across, this object is roughly 4 million times as massive as our Sun and exerts a tremendous gravitational pull.

Since that time, astronomers have discovered that most massive galaxies have SMBHs at their core, which is what separates those that have an Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN) from those that don’t. But thanks to a recent survey conducted using NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, astronomers have discovered evidence for hundreds or even thousands of black holes located near the center of the Milky Way Galaxy.

The study which described their findings was recently published in the journal Nature under the title “A density cusp of quiescent X-ray binaries in the central parsec of the Galaxy“. The study was led by Chuck Hailey, the Pupin Professor of Physics and the Co-Director of the Columbia Astrophysics Laboratory (CAL) at Columbia University, and including members from the Instituto de Astrofísica at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile and the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

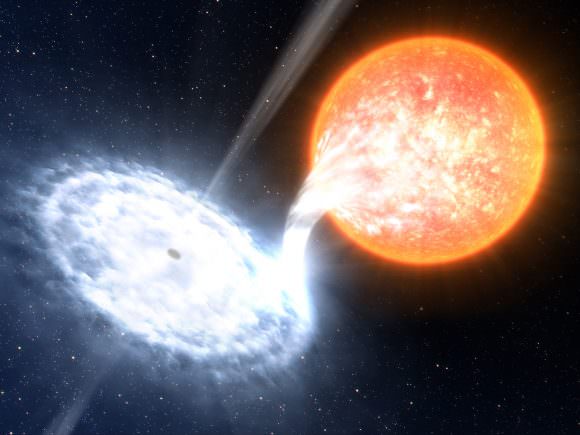

Using Chandra data, the team searched for X-ray binaries containing black holes that were in the vicinity of Sgr A*. To recap, black holes are not detectable in visible light. However, black holes (or neutron stars) that are locked in close orbits with a star will pull material from their companions, which will then be accreted onto the black holes’ disks and heated up to millions of degrees.

This will result in the release of X-rays which can then be detected, hence why these systems are called “X-ray binaries”. Using Chandra data, the team sought out X-ray of sources that were located within roughly 12 light years of Sgr A*. They then selected sources with X-ray spectra similar to those of known X-ray binaries, which emit relatively large amounts of low-energy X-rays.

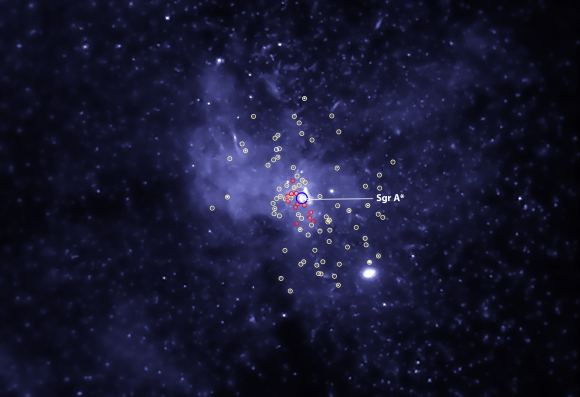

Using this method, they detected fourteen X-ray binaries within about three light years of Sgr A*, all of which contained stellar-mass black holes (between 5 and 30 times the mass of our Sun). Two of these sources had been identified by previous studies and were eliminated from the analysis, while the remaining twelve (circled in red in the image above) were newly-discovered.

Other sources which relatively large amounts of high energy X-rays (labeled in yellow) were believed to be binaries containing white dwarfs. Hailey and his colleagues concluded that the majority of the dozen X-ray binaries were likely to contain black holes, based on their variability and the fact that their X-ray emissions over the course of several years was different from what is expected from binaries containing neutron stars.

Given that only the brightest X-ray binaries containing black holes are likely to be detectable around Sgr A* (given its distance from Earth), Hailey and his colleagues concluded that this detection implies the existence of a much larger population. By their estimates, there could be at least 300 and as many as one thousand stellar-mass black holes present around Sgr A*.

These findings confirmed what theoretical studies on the dynamics of stars in galaxies have indicated in the past. According to these studies, a large population of stellar mass black holes (as many as 20,000) could drift inward over the course of millions of years and collect around an SMBH. However, the recent analysis conducted by Hailey and his colleagues was the first observational evidence of black holes congregating near Sgr A*.

Naturally, the authors acknowledge that there are other explanations for the X-ray emissions they detected. This includes the possibility that half of the dozen sources they observed are millisecond pulsars – very rapidly rotating neutron stars with strong magnetic fields. However, based on their observations, Hailey and his team strongly favor the black hole explanation.

In addition, a follow-up study conducted by Aleksey Generozov (et al.) of Columbia University – titled “An Overabundance of Black Hole X-Ray Binaries in the Galactic Center from Tidal Captures” – indicated that there could be as many as 10,000 to 40,000 black holes binaries at the center of our galaxy. According to this study, these binaries would be the result of companions being captured by black holes.

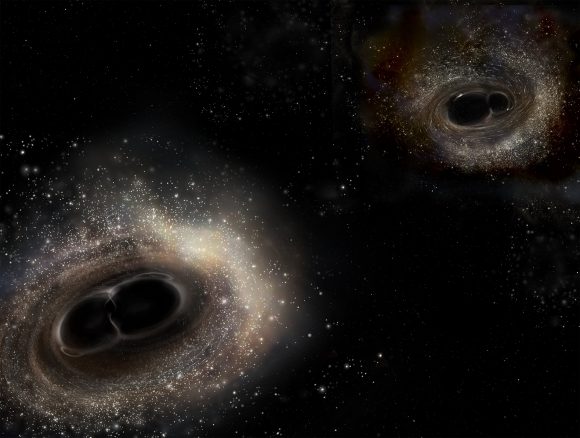

In addition to revealing much about the dynamics of stars in our galaxy, this study has implications for the emerging field of gravitational wave (GW) research. Essentially, by knowing how many black holes reside at the center of galaxies (which will periodically merge with one another), astronomers will be able to better predict how many gravitational wave events are associated with them.

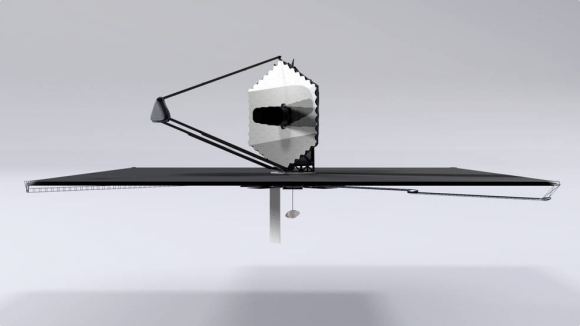

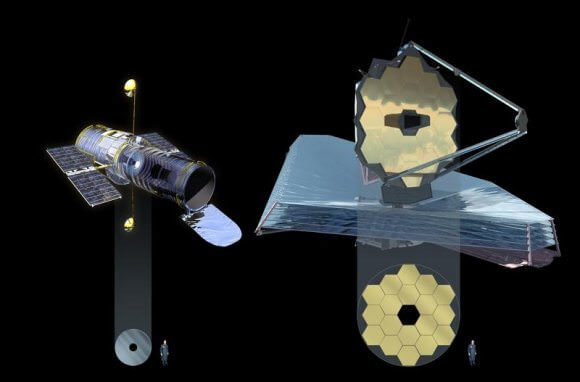

From this, astronomers could create predictive models about when and how GW events are likely to happen, and well as discerning what role they may play in galactic evolution. And with next-generation instruments – like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the ESA’s Advanced Telescope for High Energy Astrophysics (ATHENA) – astronomers will be able to determine exactly how many black holes reside near the center of our galaxy.

Further Reading: NASA