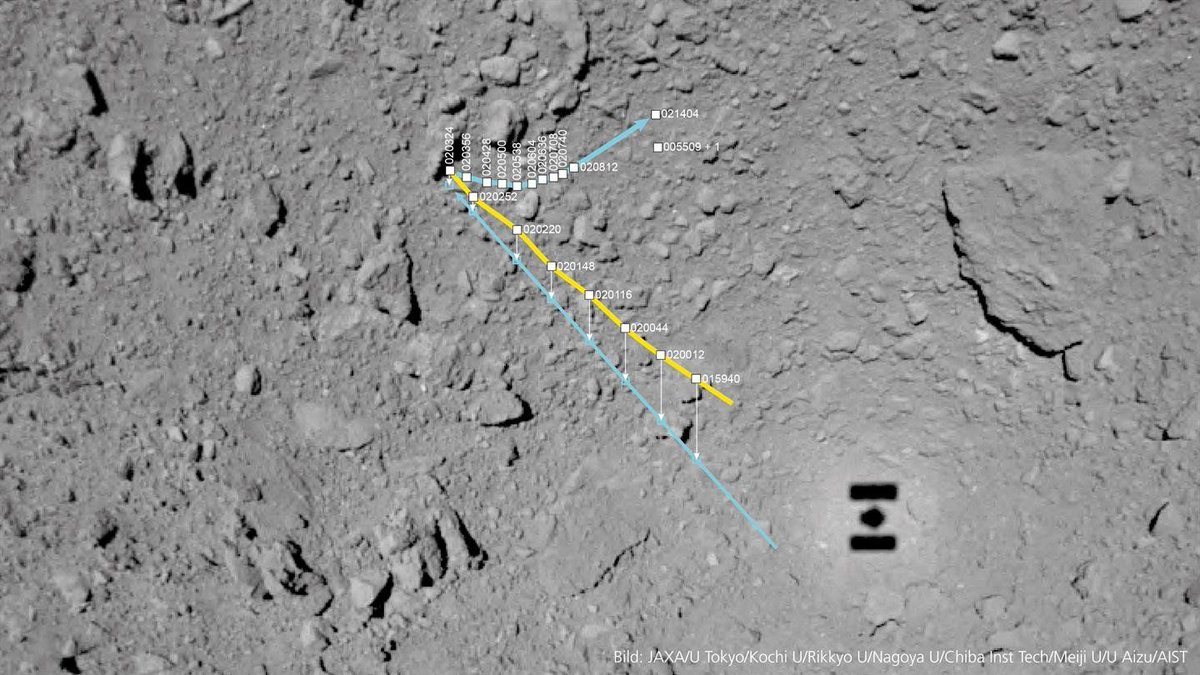

The tiny hopping-robot MASCOT completed its 17 hour mission on the asteroid Ryugu in early October. Now the German Aerospace Center (DLR) has released an image of MASCOT’s path across the asteroid. Surprised by what MASCOT found on the surface, they’ve named the landing spot “Alice’s Wonderland.”

Continue reading “The Path that MASCOT Took Across Asteroid Ryugu During its 17 Hours of Life”

The Path that MASCOT Took Across Asteroid Ryugu During its 17 Hours of Life