I apologize for the end-of-the-world title, but everything in it is true. And the world will still be here after it’s all done. On Friday (March 31) at 7:36 a.m. Central Time, the Moon will be full for the second time this month, which makes it a Blue Moon according to popular usage. Enjoy it. What with January’s Blue Moon and now this, we’ve chewed through all our Blue Moons till Halloween 2020.

I look forward to every full moon. Watching a moonrise, we get to see all manner of amazing atmospheric distortions play across the squat, orange disk. Once the sky’s dark, its outpouring of light makes walking at night a pleasure.

When a full moon occurs in spring, it hurries south down the ecliptic, the imaginary circle in the sky defining Earth’s orbit around the Sun. For northern hemisphere skywatchers, this southward sprint delays its rising by more an hour each night, forcing a quick departure from the evening sky. And that means blessed darkness for hunting down favorite galaxies and star clusters.

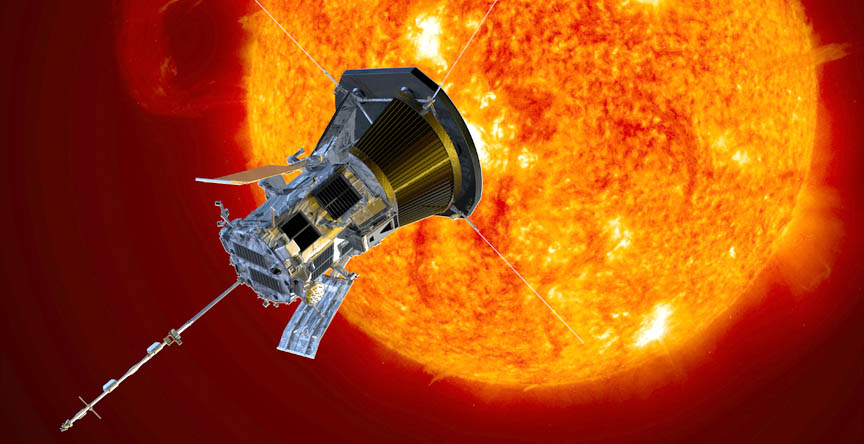

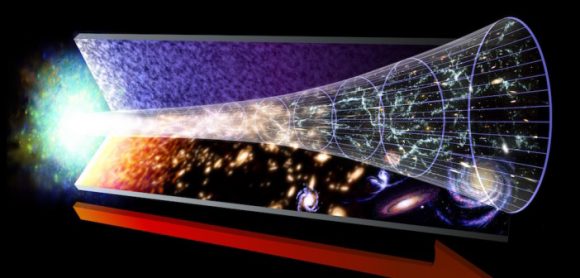

Tiangong 1 and a reentry simulation

As the Moon rolls along, the hapless Chinese space station Tiangong 1 hurtles toward Earth. Drag caused by friction with the upper atmosphere continues to shrink the spacecraft’s orbit, bringing it closer and closer to inevitable breakup and incineration. Since the Chinese National Space Administration (CNSA) lost touch with Tiangong 1 in March 2016, mission control can no longer power thrusters to de-orbit it at chosen time over a safe location like the ocean. The 9.3-ton (8,500 kg) station will burn up somewhere anywhere over a vast swath of the planet between latitudes 43°N and 43°S. Included within this zone are the southern half of Europe, the southern two-thirds of the U.S., India, Australia and much of Africa and South America.

Not until the day of or even hours before will have a clear idea of when and where the station will meet its fate. According to the latest update from the Aerospace Corp., which monitors falling spacecraft, reentry is expected on Easter Sunday (April 1) at 10:30 UT / 5:30 a.m. Central Time plus or minus 16 hours. This morning (March 29), the space station is circling Earth at about 118 miles (190 km) altitude. The lowest a satelllite can still make a complete orbit of the planet is about 62 miles (100 km). Below that, break-up begins.

For up-to-the-minute updates on when to expect Tiangong 1’s orbit to decay and the machine to plunge to Earth, check out Joseph Remis’ Twitter page. Most of the space station is expected to burn up on reentry, but larger chunks might survive all the way to the ground. Since much more of the Earth’s surface is water these remnants will likely end up in the drink … but you never know. If Tiangong-1 does come down over a populated area, observers on the ground will witness a spectacular, manmade fireball day or night.

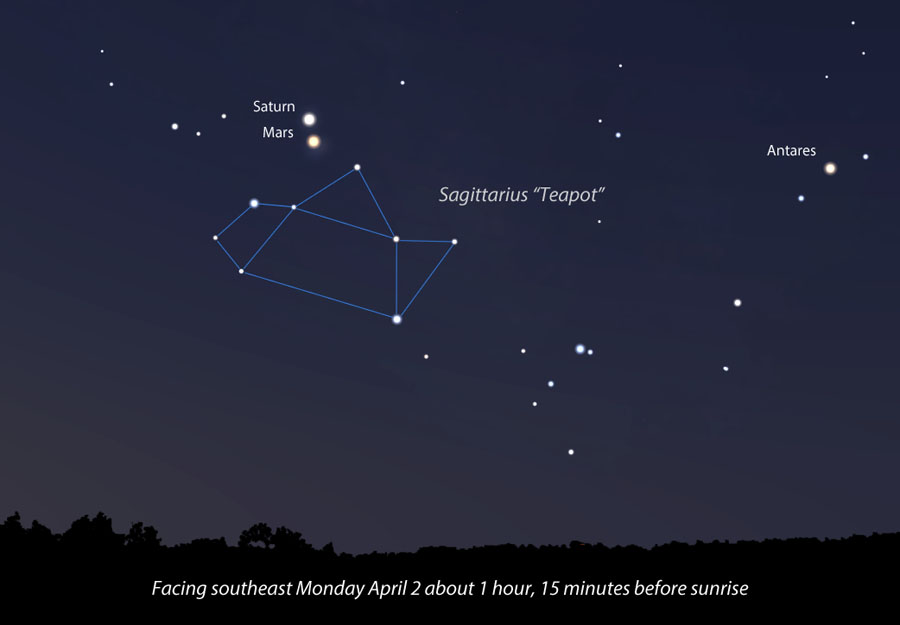

On the quieter side but nearly as eye-catching, Mars will overtake Saturn in the coming week, passing just 1° south of the ringed planet in a thrilling dawn conjunction on April 2. If the weather forecast doesn’t look promising that morning, the two planets will remain within 2° of each other now through April 6th, providing plenty of opportunities for a look.

You can easily tell them apart by color: Mars is distinctly red-orange and Saturn looks creamy white. Both are bright at around magnitude 0 though Mars is now a hair brighter by two-tenths of a magnitude. Will you be able to see the difference?

In most telescopes at low magnification both planets will comfortably fit in the same field of view. Saturn’s rings are tilted nearly wide open and quite beautiful. Mars appears gibbous and though still rather small, it’s brightening rapidly and drawing closer in time for its closest approach to Earth since 2003. Wishing you clear skies!