In 1915, Albert Einstein published his famous Theory of General Relativity, which provided a unified description of gravity as a geometric property of space and time. This theory gave rise to the modern theory of gravitation and revolutionized our understanding of physics. Even though a century has passed since then, scientists are still conducting experiments that confirm his theory’s predictions.

Thanks to recent observations made by a team of international astronomers (known as the GRAVITY collaboration), the effects of General Relativity have been revealed using a Supermassive Black Hole (SMBH) for the very first time. These findings were the culmination of a 26-year campaign of observations of the SMBH at the center of the Milky Way (Sagittarius A*) using the European Southern Observatory‘s (ESO) instruments.

The study which describes the team’s findings recently appeared in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics, titled “Detection of the gravitational redshift in the orbit of the star S2 near the Galactic centre massive black hole“. The study was led by Roberto Arbuto of the ESO and included members from the GRAVITY collaboration – which is led by Reinhard Genzel of the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics (MPE) and includes astronomers from multiple European universities and research institutes.

For the sake of their study, the team relied on data gathered by the VLT’s extremely sensitive and high-precision instruments. These included the GRAVITY astrometric and interferometry instrument, the Spectrograph for INtegral Field Observations in the Near Infrared (SINFONI) instrument, and the Nasmyth Adaptive Optics System (NAOS) – Near-Infrared Imager and Spectrograph (CONICA) instrument, which are together known as NACO.

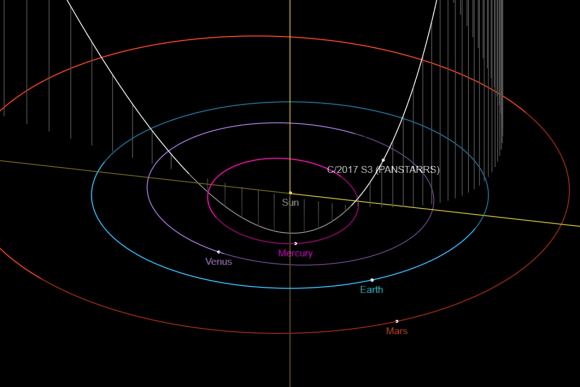

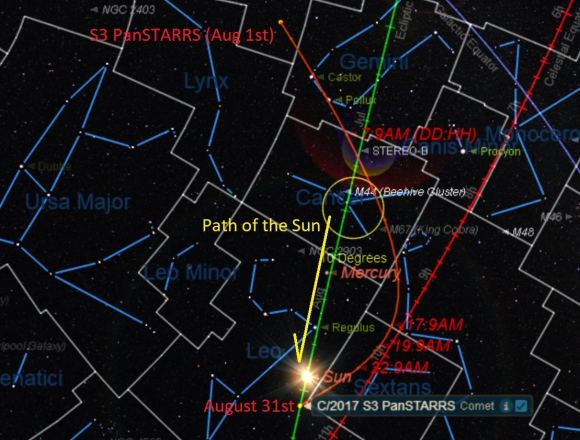

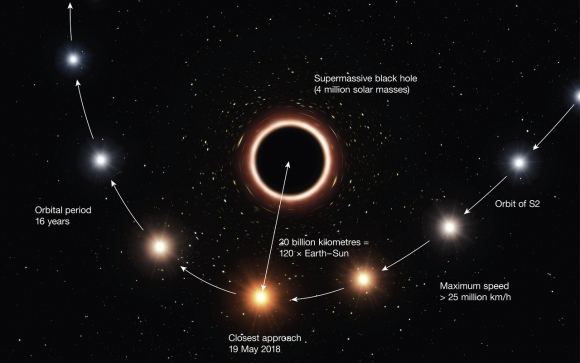

The new infrared observations collected by these instruments allowed the team to monitor one of the stars (S2) that orbits Sagittarius A* as it passed in front of the black hole – which took place in May of 2018. At the closest point in its orbit, the star was at a distance of less than 20 billion km (12.4 billion mi) from the black hole and was moving at a speed in excess of 25 million km/h (15 million mph) – almost three percent of the speed of light.

Whereas the SINFONI instrument was used to measure the velocity of S2 towards and away from Earth, the GRAVITY instrument in the VLT Interferometer (VLTI) made extraordinarily precise measurements of the changing position of S2 in order to define the shape of its orbit. The GRAVITY instrument then created the sharp images that revealed the motion of the star as it passed close to the black hole.

The team then compared the position and velocity measurements to previous observations of S2 using other instruments. They then compared these results with predictions made by Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation, General Relativity, and other theories of gravity. As expected, the new results were consistent with the predictions made by Einstein over a century ago.

As Reinhard Genzel, who in addition to being the leader of the GRAVITY collaboration was a co-author on the paper, explained in a recent ESO press release:

“This is the second time that we have observed the close passage of S2 around the black hole in our galactic center. But this time, because of much improved instrumentation, we were able to observe the star with unprecedented resolution. We have been preparing intensely for this event over several years, as we wanted to make the most of this unique opportunity to observe general relativistic effects.”

When observed with the VLT’s new instruments, the team noted an effect called gravitational redshift, where the light coming from S2 changed color as it drew closer to the black hole. This was caused by the very strong gravitational field of the black hole, which stretched the wavelength of the star’s light, causing it to shift towards the red end of the spectrum.

The change in the wavelength of light from S2 agrees precisely with what Einstein’s field equation’s predicted. As Frank Eisenhauer – a researcher from the Max Planck Institute of Extraterrestrial Physics, the Principal Investigator of GRAVITY and the SINFONI spectrograph, and a co-author on the study – indicated:

“Our first observations of S2 with GRAVITY, about two years ago, already showed that we would have the ideal black hole laboratory. During the close passage, we could even detect the faint glow around the black hole on most of the images, which allowed us to precisely follow the star on its orbit, ultimately leading to the detection of the gravitational redshift in the spectrum of S2.”

Whereas other tests have been performed that have confirmed Einstein’s predictions, this is the first time that the effects of General Relativity have been observed in the motion of a star around a supermassive black hole. In this respect, Einstein has been proven right once again, using one the most extreme laboratory to date! What’s more, it confirmed that tests involving relativistic effects can provide consistent results over time and space.

“Here in the Solar System we can only test the laws of physics now and under certain circumstances,” said Françoise Delplancke, head of the System Engineering Department at ESO. “So it’s very important in astronomy to also check that those laws are still valid where the gravitational fields are very much stronger.”

In the near future, another relativistic test will be possible as S2 moves away from the black hole. This is known as a Schwarzschild precession, where the star is expected to experience a small rotation in its orbit. The GRAVITY Collaboration will be monitoring S2 to observe this effect as well, once again relying on the VLT’s very precise and sensitive instruments.

As Xavier Barcons (the ESO’s Director General) indicated, this accomplishment was made possible thanks to the spirit of international cooperation represented by the GRAVITY collaboration and the instruments they helped the ESO develop:

“ESO has worked with Reinhard Genzel and his team and collaborators in the ESO Member States for over a quarter of a century. It was a huge challenge to develop the uniquely powerful instruments needed to make these very delicate measurements and to deploy them at the VLT in Paranal. The discovery announced today is the very exciting result of a remarkable partnership.”

And be sure to check out this video of the GRAVITY Collaboration’s successful test, courtesy of the ESO:

Further Reading: ESO, Astronomy and Astrophysics