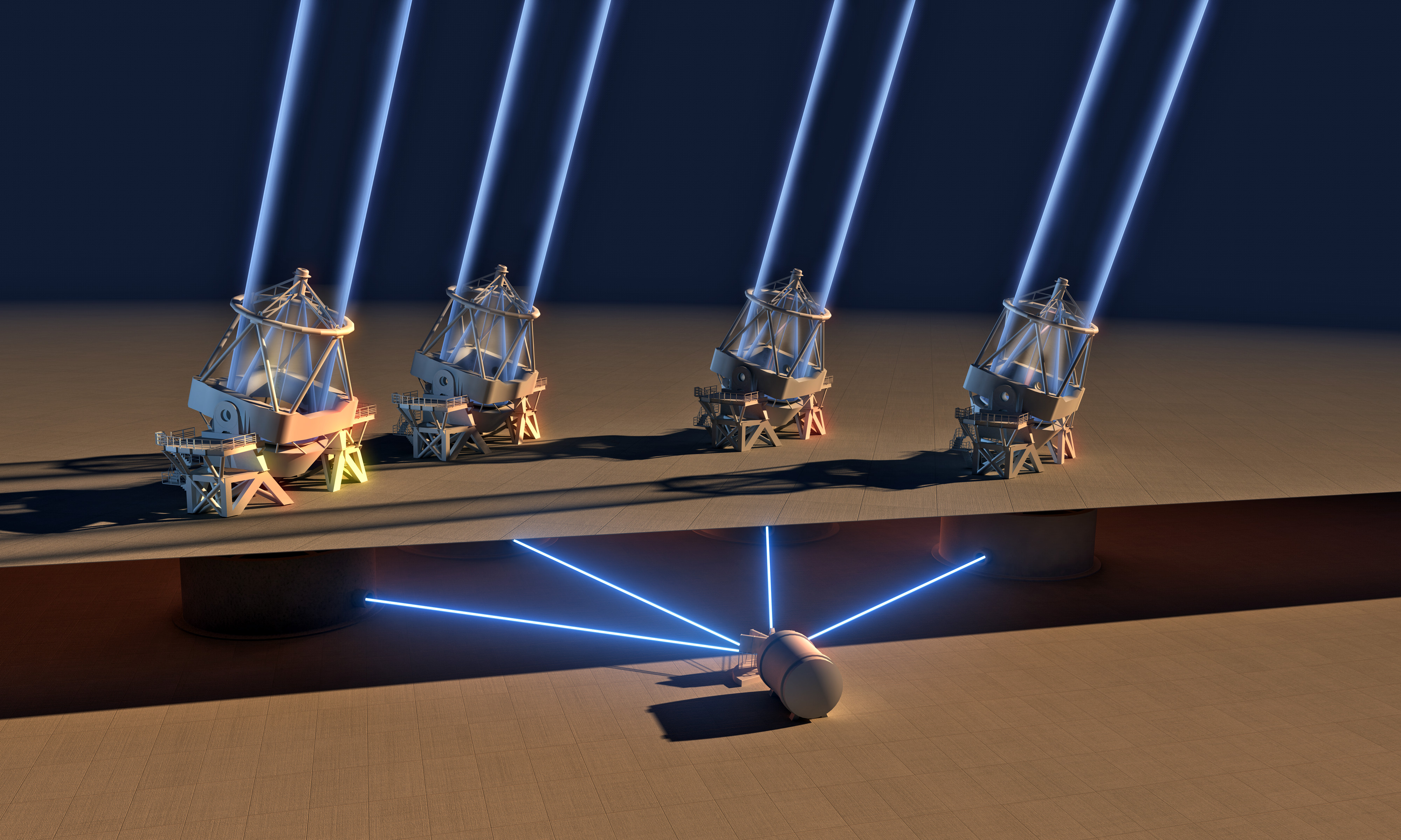

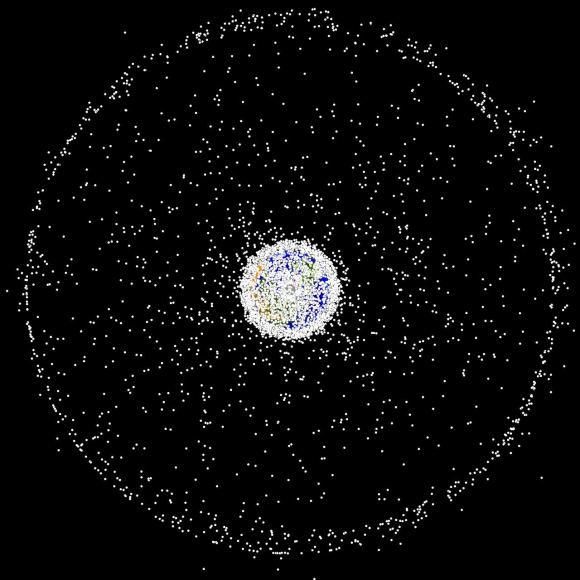

After sixty years of space agencies sending rockets, satellites and other missions into orbit, space debris has become something of a growing concern. Not only are there large pieces of junk that could take out a spacecraft in a single hit, but there are also countless tiny pieces of debris traveling at very high speeds. This debris poses a serious threat to the International Space Station (ISS), active satellites and future crewed missions in orbit.

For this reason, the European Space Agency is looking to develop better debris shielding for the ISS and future generations of spacecraft. This project, which is supported through the ESA’s General Support Technology Programme, recently conducted ballistics tests that looked at the efficiency of new fiber metal laminates (FMLs), which may replace aluminum shielding in the coming years.

To break it down, any and all orbital missions – be they satellites or space stations – need to be prepared for the risk of high-speed collisions with tiny objects. This includes the possibility of colliding with human-made space junk, but also includes the risk of micro-meteoroid object damage (MMOD). These are especially threatening during intense seasonal meteoroid streams, such as the Leonids.

While larger pieces of orbital debris – ranging from 5 cm (2 inches) to 1 meter (1.09 yards) in diameter – are regularly monitored by NASA and and the ESA’s Space Debris Office, the smaller pieces are undetectable – which makes them especially threatening. To make matters worse, collisions between bits of debris can cause more to form, a phenomena known as the Kessler Effect.

And since humanity’s presence Near-Earth Orbit (NEO) is only increasing, with thousands of satellites, space habitats and crewed missions planned for the coming decades, growing levels of orbital debris therefore pose an increasing risk. As engineer Andreas Tesch explained:

“Such debris can be very damaging because of their high impact speeds of multiple kilometres per second. Larger pieces of debris can at least be tracked so that large spacecraft such as the International Space Station can move out of the way, but pieces smaller than 1 cm are hard to spot using radar – and smaller satellites have in general fewer opportunities to avoid collision.”

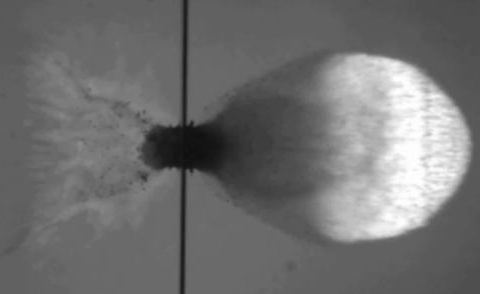

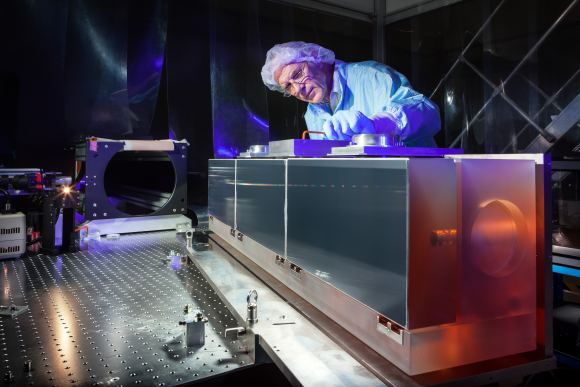

To see how their new shielding would hold up to space debris, a team of ESA researchers recently conducted a test where a 2.8 mm-diameter aluminum bullet was fired at sample of spacecraft shield – the results of which were filmed by a high-speed camera. At this size, and with a speed of 7 km/s, the bullet effectively simulated the impact energy that a small piece of debris would have as if it came into contact with the ISS.

As researcher Benoit Bonvoisin explained in a recent ESA press release:

“We used a gas gun at Germany’s Fraunhofer Institute for High-Speed Dynamics to test a novel material being considered for shielding spacecraft against space debris. Our project has been looking into various kinds of ‘fibre metal laminates’ produced for us by GTM Structures, which are several thin metal layers bonded together with composite material.”

As you can see from the video (posted above), the solid aluminum bullet penetrated the shield but then broke apart into a could of fragments and vapor, which are much easier for the next layer of armor to capture or deflect. This is standard practice when dealing with space debris and MMOD, where multiple shields are layered together to adsorb and capture the impact so that it doesn’t penetrate the hull.

An common variant of this is known as the ‘Whipple shield’, which was originally devised to guard against comet dust. This shielding consists of two layers, a bumper and a rear wall, with a mutual distance of 10 to 30 cm (3.93 to 11.8 inches). In this case, the FML, which is produced for the ESA by GTM Structures BV (a Netherlands-based aerospace company), consists of several thin metal layers bonded together with a composite material.

Based on this latest test, the FML appears to be well-suited at preventing damage to the ISS and future space stations. As Benoit indicated, he and his colleagues now need to test this shielding on other types of orbital missions. “The next step would be to perform in-orbit demonstration in a CubeSat, to assess the efficiency of these FMLs in the orbital environment,” he said.

And be sure to enjoy this video from the ESA’s Orbital Debris Office:

Further Reading: ESA