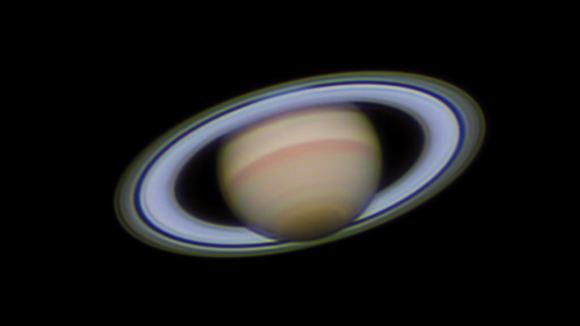

Even though the Cassini orbiter ended its mission on of September 15th, 2017, the data it gathered on Saturn and its largest moon, Titan, continues to astound and amaze. During the thirteen years that it spent orbiting Saturn and conducting flybys of its moons, the probe gathered a wealth of data on Titan’s atmosphere, surface, methane lakes, and rich organic environment that scientists continue to pore over.

For instance, there is the matter of the mysterious “sand dunes” on Titan, which appear to be organic in nature and whose structure and origins remain have remained a mystery. To address these mysteries, a team of scientists from John Hopkins University (JHU) and the research company Nanomechanics recently conducted a study of Titan’s dunes and concluded that they likely formed in Titan’s equatorial regions.

Their study, “Where does Titan Sand Come From: Insight from Mechanical Properties of Titan Sand Candidates“, recently appeared online and has been submitted to the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. The study was led by Xinting Yu, a graduate student with the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences (EPS) at JHU, and included EPS Assistant Professors Sarah Horst (Yu’s advisor) Chao He, and Patricia McGuiggan, with support provided by Bryan Crawford of Nanomechanics Inc.

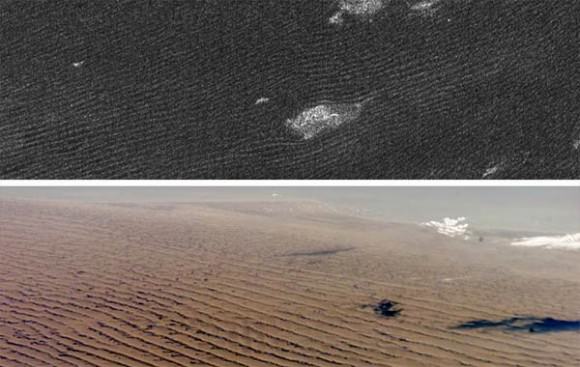

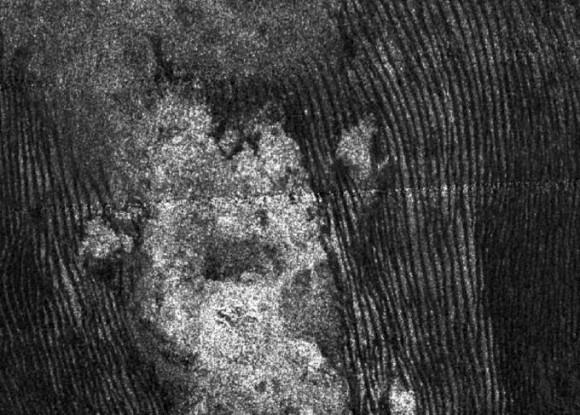

To break it down, Titan’s sand dunes were originally spotted by Cassini’s radar instruments in the Shangri-La region near the equator. The images the probe obtained showed long, linear dark streaks that looked like wind-swept dunes similar to those found on Earth. Since their discovery, scientists have theorized that they are comprised of grains of hydrocarbons that have settled on the surface from Titan’s atmosphere.

In the past, scientists have conjectured that they form in the northern regions around Titan’s methane lakes and are distributed to the equatorial region by the moon’s winds. But where these grains actually came from, and how they came to be distributed in these dune-like formations, has remained a mystery. However, as Yu explained to Universe Today via email, that is only part of what makes these dunes mysterious:

“First, nobody expected to see any sand dunes on Titan before the Cassini-Huygens mission, because global circulation models predicted the wind speeds on Titan are too weak to blow the materials to form dunes. However, through Cassini we saw vast linear dune fields that covers almost 30% of the equatorial regions of Titan!

“Second, we are not sure how Titan sands are formed.Dune materials on Titan are completely different from those on Earth. On Earth, dune materials are mainly silicate sand fragments weathered from silicate rocks. While on Titan, dune materials are complex organics formed by photochemistry in the atmosphere, falling to the ground. Studies show that the dune particles are pretty big (at least 100 microns), while the photochemistry formed organic particles are still pretty small near the surface (only around 1 micron). So we are not sure how the small organic particles are transformed into the big sand dune particles (you need a million small organic particles to form one single sand particle!)

“Third, we also don’t know where the organic particles in the atmosphere are processed to become bigger to form the dune particles. Some scientists think these particles can be processed everywhere to form the dune particles, while some other researchers believe their formation need to be involved with Titan’s liquids (methane and ethane), which are currently located only in the polar regions.”

To shed light on this, Yu and her colleagues conducted a series of experiments to simulate materials being transported on both terrestrial and icy bodies. This consisted of using several natural Earth sands, such as silicate beach sand, carbonate sand and white gyspum sand. To simulate the kinds materials found on Titan, they used laboratory-produced tholins, which are molecules of methane that have been subjected to UV radiation.

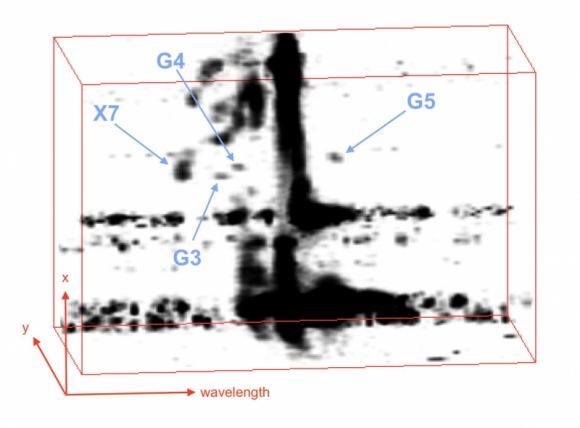

The production of tholins was specifically conducted to recreate the kinds of organic aerosols and photochemistry conditions that are common on Titan. This was done using the Planetary HAZE Research (PHAZER) experimental system at Johns Hopkins University – for which the Principal Investigator is Sarah Horst. The last step consisted of using a nanoidentification technique (overseen by Bryan Crawford of Nanometrics Inc.) to study the mechanical properties of the simulated sands and tholins.

This consisted of placing the sand simulants and tholins into a wind tunnel to determine their mobility and see if they could be distributed in the same patterns. As Yu explained:

“The motivation behind the study is to try to answer the third mystery. If the dune materials are processed through liquids, which are located in the polar regions of Titan, they need to be strong enough to be transported from the poles to the equatorial regions of Titan, where most of the dunes are located. However, the tholins we produced in the lab are in extremely low amounts: the thickness of the tholin film we produced is only around 1 micron, about 1/10-1/100 of the thickness of human hair. To deal with this, we used a very intriguing and precise nanoscale technique called nanoindentation to perform the measurements. Even though the produced indents and cracks are all in nanometer scales, we can still precisely determine mechanical properties like Young’s modulus (indicator of stiffness), nanoindentation hardness (hardness), and fracture toughness (indicator of brittleness) of the thin film.”

In the end, the team determined that the organic molecules found on Titan are much softer and more brittle when compared to even the softest sands on Earth. Simply put, the tholins they produced did not appear to have the strength to travel the immense distance that lies between Titan’s northern methane lakes and the equatorial region. From this, they concluded that the organic sands on Titan are likely formed near where they are located.

“And their formation may not involve liquids on Titan, since that would require a huge transportation distance of over 2000 kilometers from the Titan’s poles to the equator,” Yu added. “The soft and brittle organic particles would be grinded to dust before they reach the equator. Our study used a completely different method and reinforced some of results inferred from Cassini observations.”

In the end, this study represents a new direction for researchers when it comes to the study of Titan and other bodies in the Solar System. As Yu explained, in the past, researchers were mostly constrained with Cassini data and modelling to answer questions about Titan’s sand dunes. However, Yu and her colleagues were able to use laboratory-produced analogs to address these questions, despite the fact that the Cassini mission is now at an end.

What’s more, this most recent study is sure to be of immense value as scientists continue to pore over Cassini’s data in anticipation of future missions to Titan. These missions aim to study Titan’s sand dunes, methane lakes and rich organic chemistry in more detail. As Yu explained:

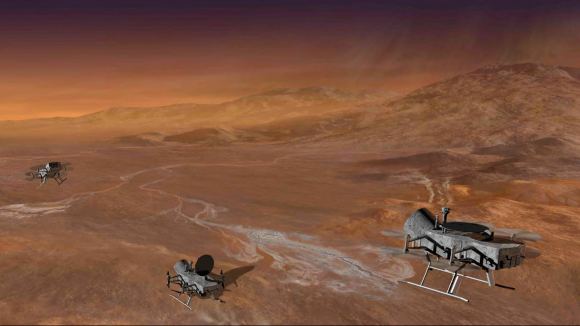

“[O]ur results can not only help understand the origin of Titan’s dunes and sands, but also it will provide crucial information for potential future landing missions on Titan, such as Dragonfly (one of two finalists (out of twelve proposals) selected for further concept development by NASA’s New Frontiers program). The material properties of the organics on Titan can actually provide amazing clues to solve some of the mysteries on Titan.

“In a study we published last year in JGR-planets (2017, 122, 2610–2622), we found out that the interparticle forces between tholin particles are much larger than common sand on Earth, which means the organics on Titan are much more cohesive (or stickier) than silicate sands on Earth. This implies that we need a larger wind speed to blow the sand particles on Titan, which could help the modeling researchers to answer the first mystery. It also suggests that Titan sands could be formed by simple coagulation of organic particles in the atmosphere, since they are much easier to stick together. This could help understand the second mystery of Titan’s sand dunes.”

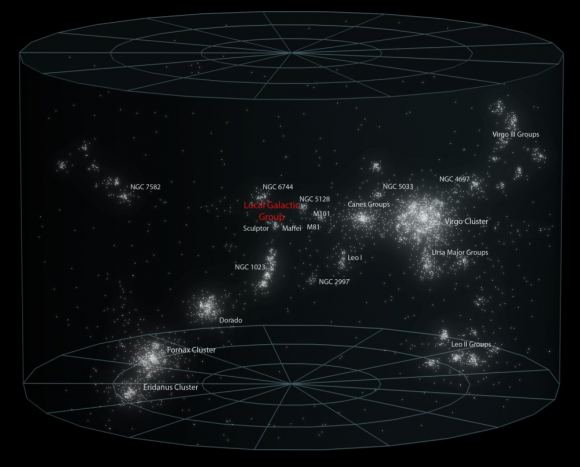

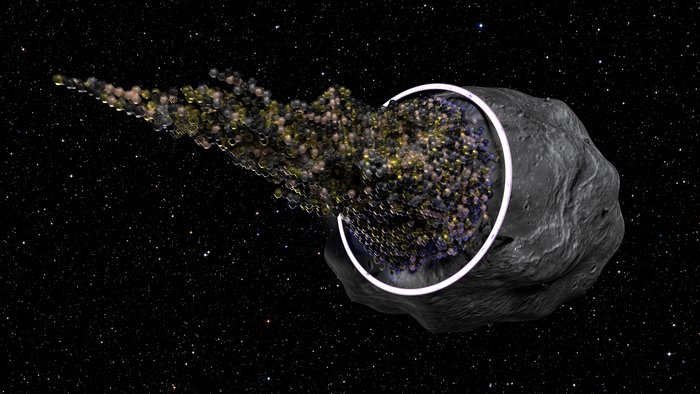

In addition, this study has implications for the study of bodies other than Titan. “We have found organics on many other solar system bodies, especially icy bodies in the outer solar system, such as Pluto, Neptune’s moon Triton, and comet 67P,” said Yu. “And some of the organics are photochemically produced similarly to Titan. And we do found wind blown features (called aeolian features) on those bodies as well, so our results could be applied to these planetary bodies as well.”

In the coming decade, multiple missions are expected to explore the moons of the outer Solar System and reveal things about their rich environments that could help shed light on the origins of life here on Earth. In addition, the James Webb Space Telescope (now expected to be deployed in 2021) will also use its advanced suit of instruments to study the planets of the Solar System in the hopes of address these burning questions.

Further Reading: arXiv