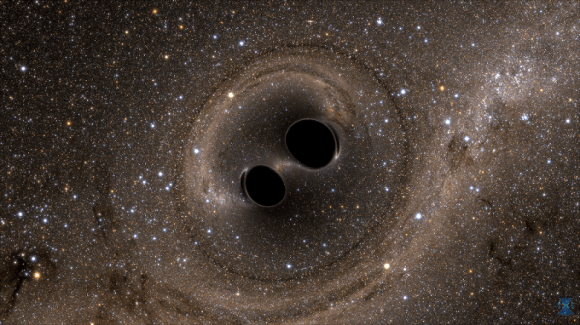

In February of 2016, scientists working at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) made history when they announced the first-ever detection of gravitational waves. Since that time, the study of gravitational waves has advanced considerably and opened new possibilities into the study of the Universe and the laws which govern it.

For example, a team from the University of Frankurt am Main recently showed how gravitational waves could be used to determine how massive neutron stars can get before collapsing into black holes. This has remained a mystery since neutron stars were first discovered in the 1960s. And with an upper mass limit now established, scientists will be able to develop a better understanding of how matter behaves under extreme conditions.

The study which describes their findings recently appeared in the scientific journal The Astrophysical Journal Letters under the title “Using Gravitational-wave Observations and Quasi-universal Relations to Constrain the Maximum Mass of Neutron Stars“. The study was led by Luciano Rezzolla, the Chair of Theoretical Astrophysics and the Director of the Institute for Theoretical Physics at the University of Frankfurt, with assistance provided by his students, Elias Most and Lukas Wei.

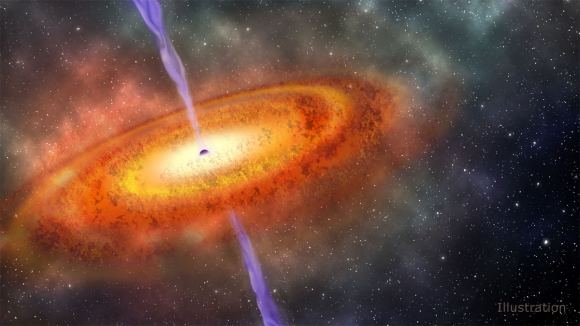

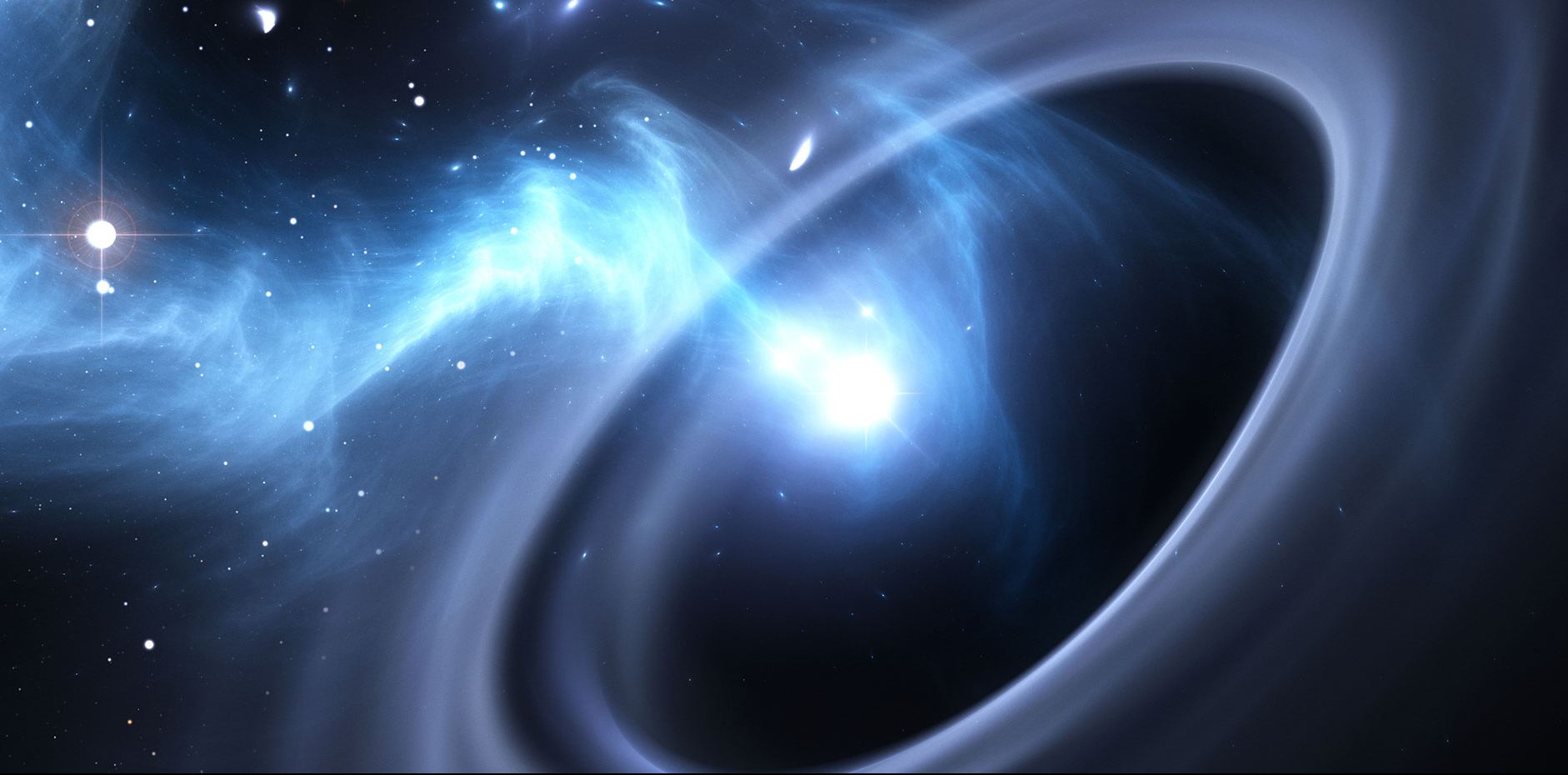

For the sake of their study, the team considered recent observations made of the gravitational wave event known as GW170817. This event, which took place on August 17th, 2017, was the sixth gravitational wave to be discovered by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) and Virgo Observatory. Unlike previous events, this one was unique in that it appeared to be caused by the collision and explosion of two neutron stars.

And whereas other events occurred at distances of about a billion light years, GW170817 took place only 130 million light years from Earth, which allowed for rapid detection and research. In addition, based on modeling that was conducted months after the event (and using data obtained by the Chandra X-ray Observatory) the collision appeared to have left behind a black hole as a remnant.

The team also adopted a “universal relations” approach for their study, which was developed by researchers at Frankfurt University a few years ago. This approach implies that all neutron stars have similar properties which can be expressed in terms of dimensionless quantities. Combined with the GW data, they concluded that the maximum mass of non-rotating neutron stars cannot exceed 2.16 solar masses.

As Professor Rezzolla explained in a University of Frankfurt press release:

“The beauty of theoretical research is that it can make predictions. Theory, however, desperately needs experiments to narrow down some of its uncertainties. It’s therefore quite remarkable that the observation of a single binary neutron star merger that occurred millions of light years away combined with the universal relations discovered through our theoretical work have allowed us to solve a riddle that has seen so much speculation in the past.”

This study is a good example of how theoretical and experimental research can coincide to produce better models ad predictions. A few days after the publication of their study, research groups from the USA and Japan independently confirmed the findings. Just as significantly, these research teams confirmed the studies findings using different approaches and techniques.

In the future, gravitational-wave astronomy is expected to observe many more events. And with improved methods and more accurate models at their disposal, astronomers are likely to learn even more about the most mysterious and powerful forces at work in our Universe.

Further Reading: Goethe University Frankfurt am Main, The Astrophysical Journal Letters