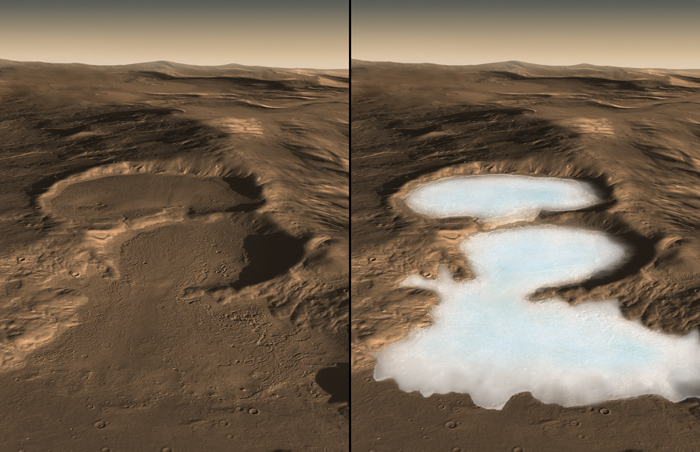

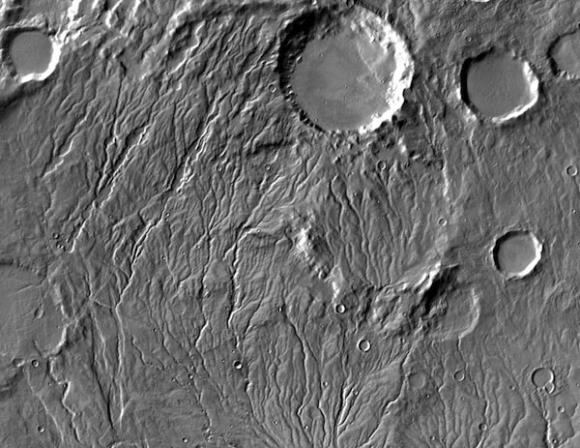

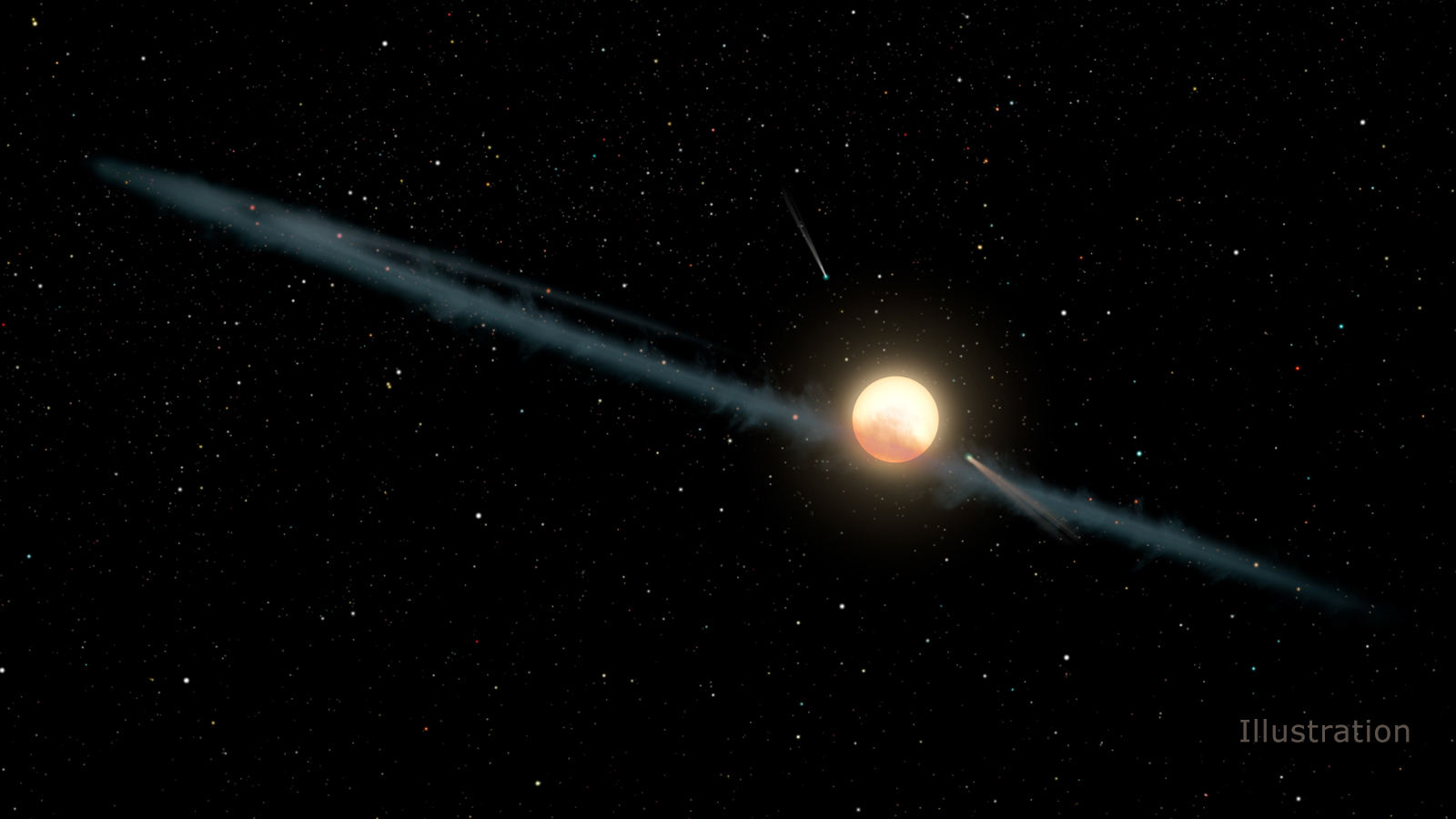

Today, there are multiple lines of evidence that indicate that during the Noachian period (ca. 4.1 to 3.7 billion years ago), microorganisms could have existed on the surface of Mars. These include evidence of past water flows, rivers and lakebeds, as well as atmospheric models that indicate that Mars once had a denser atmosphere. All of this adds up to Mars having once been a warmer and wetter place than it is today.

However, to date, no evidence has been found that life ever existed on Mars. As a result, scientists have been trying to determine how and where they should look for signs of past life. According to a new study by a team of European researchers, extreme lifeforms that are capable of metabolizing metals could have existed on Mars in the past. The “fingerprints” of their existence could be found by looking at samples of Mars’ red sands.

For the sake of their study, which recently appeared in the scientific journal Frontiers of Microbiology, the team created a “Mars Farm” to see how a form of extreme bacteria might fare in an ancient Martian environment. This environment was characterized by a comparatively thin atmosphere composed of mainly of carbon dioxide, as well as simulated samples of Martian regolith.

They then introduced a strain of bacteria known as Metallosphaera sedula, which thrives in hot, acidic environments. In fact, the bacteria’s optimal conditions are those where temperatures reach 347.1 K (74 °C; 165 °F) and pH levels are 2.0 (between lemon juice and vinegar). Such bacteria are classified as chemolithotrophs, which means that they are able to metabolize inogranic metals – like iron, sulfur and even uranium.

These stains of bacteria were then added to the samples of regolith that were designed to mimic conditions in different locations and historical periods on Mars. First, there was sample MRS07/22, which consisted of a highly-porous type of rock that is rich in silicates and iron compounds. This sample simulated the kinds of sediments found on the surface of Mars.

Then there was P-MRS, a sample that was rich in hydrated minerals, and the sulfate-rich S-MRS sample, which mimic Martian regolith that was created under acidic conditions. Lastly, there was the sample of JSC 1A, which was largely composed of the volcanic rock known as palagonite. With these samples, the team was able to see exactly how the presence of extreme bacteria would leave biosignatures that could be found today.

As Tetyana Milojevic – an Elise Richter Fellow with the Extremophiles Group at the University of Vienna and a co-author on the paper – explained in a University of Vienna press release:

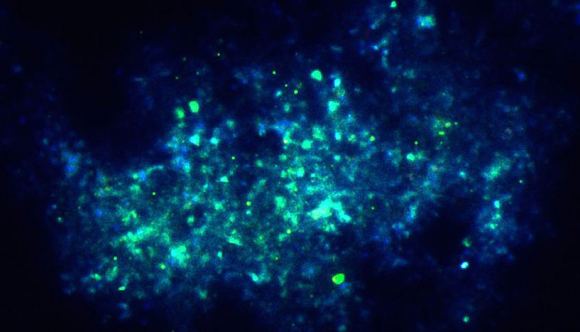

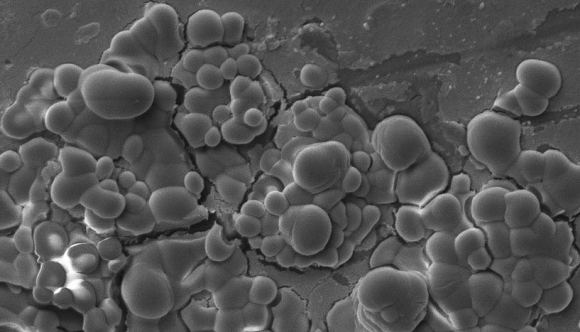

“We were able to show that due to its metal oxidizing metabolic activity, when given an access to these Martian regolith simulants, M. sedula actively colonizes them, releases soluble metal ions into the leachate solution and alters their mineral surface leaving behind specific signatures of life, a ‘fingerprint’, so to say.”

The team then examined the samples of regolith to see if they had undergone any bioprocessing, which was possible thanks to the assistance of Veronika Somoza – a chemist from the University of Vienna’s Department of Physiological Chemistry and a co-author on the study. Using an electron microscope, combined with analytical spectroscopy technique, the team sought to determine if metals with the samples had been consumed.

In the end, the sets of microbiological and mineralogical data they obtained showed signs of free soluble metals, which indicated that the bacteria had effectively colonized the regolith samples and metabolized some of the metallic minerals within. As Milojevic indicated:

“The obtained results expand our knowledge of biogeochemical processes of possible life beyond Earth, and provide specific indications for detection of biosignatures on extraterrestrial material – a step further to prove potential extra-terrestrial life.”

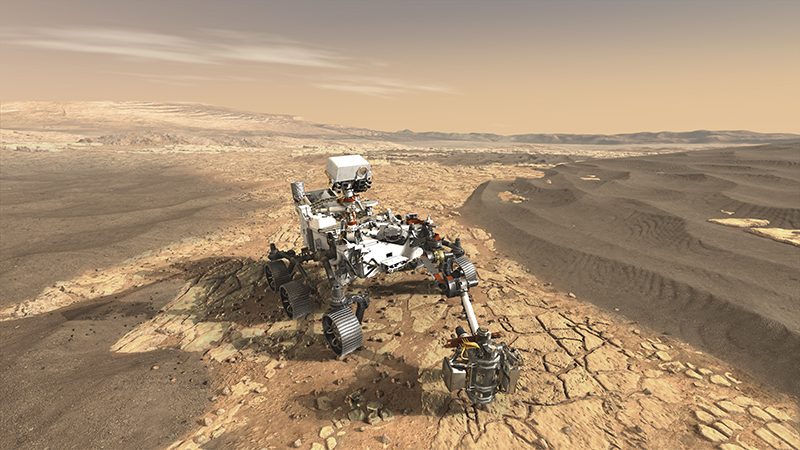

In effect, this means that extreme bacteria could have existed on Mars billions of years ago. And thanks to the state of Mars today – with its thin atmosphere and lack of precipitation – the biosignatures they left behind (i.e. traces of free soluble metals) could be preserved within Martian regolith. These biosignatures could therefore be detected by upcoming sample-return missions, such as the Mars 2020 rover.

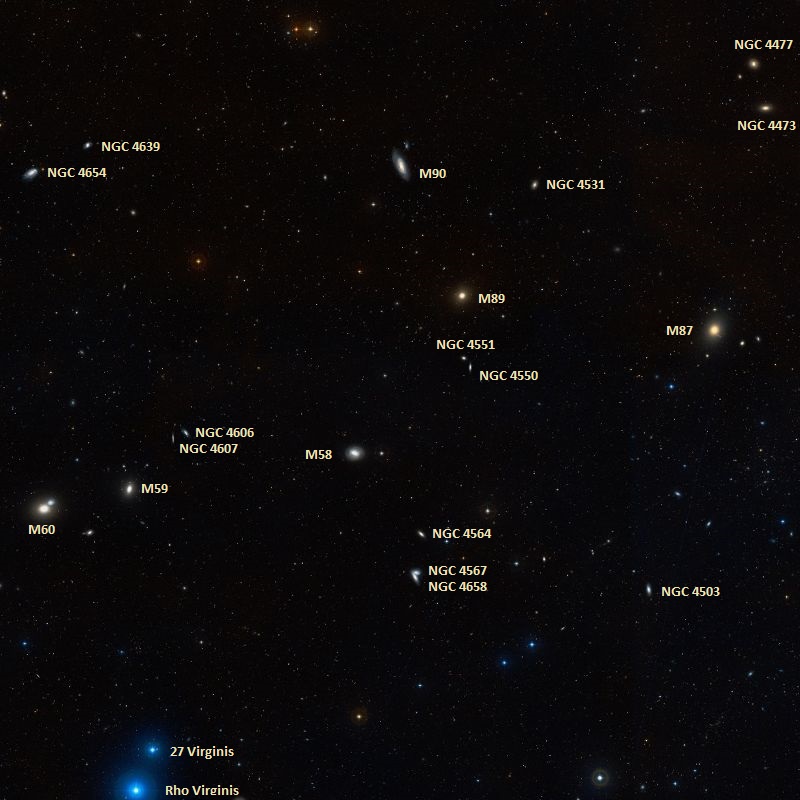

In addition to pointing the way towards possible indications of past life on Mars, this study is also significant as far as the hunt for life on other planets and star systems is concerned. In the future, when we are able to study extra-solar planets directly, scientists will likely be looking for signs of biominerals. Among other things, these “fingerprints” would be a powerful indicator of the existence of extra-terrestrial life (past or present).

Studies of extreme lifeforms and the role they play in the geological history of Mars and other planets is also helpful in advancing our understanding of how life emerged in the early Solar System. On Earth too, extreme bacteria played an important role in turning the primordial Earth into a habitable environment, and play an important role in geological processes today.

Last, but not least, studies of this nature could also pave the way for biomining, a technique where strains of bacteria extract metals from ores. Such a process could be used for the sake of space exploration and resource exploitation, where colonies of bacteria are sent out to mine asteroids, meteors and other celestial bodies.

Further Reading: University of Vienna, Frontiers in Microbiology