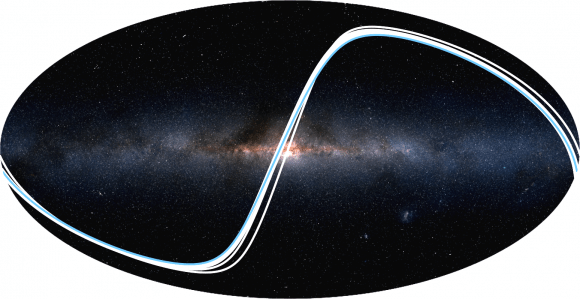

Since it was launched in 2009, NASA’s Kepler mission has continued to make important exoplanet discoveries. Even after the failure of two reaction wheels, the space observatory has found new life in the form of its K2 mission. All told, this space observatory has detected 5,017 candidates and confirmed the existence of 2,494 exoplanets using the Transit Method during its past eight years in service.

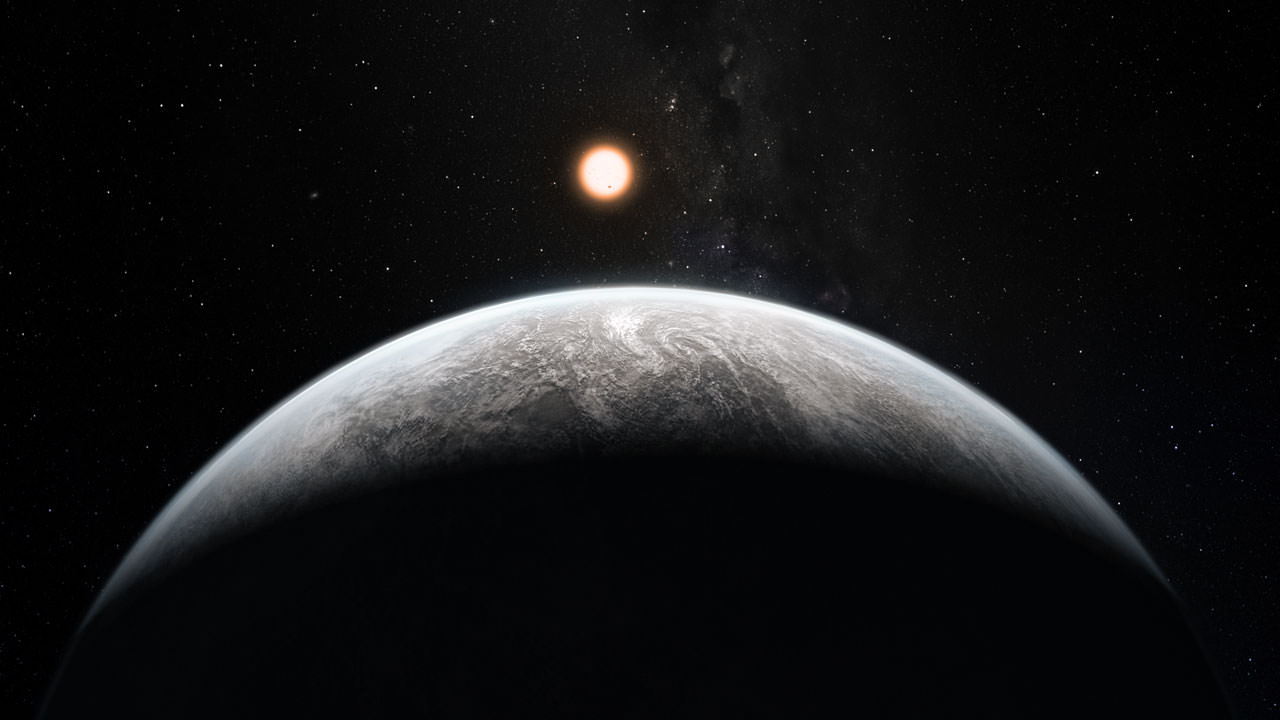

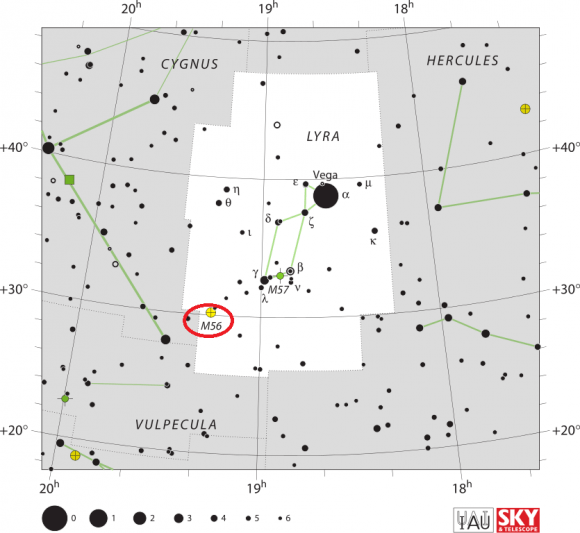

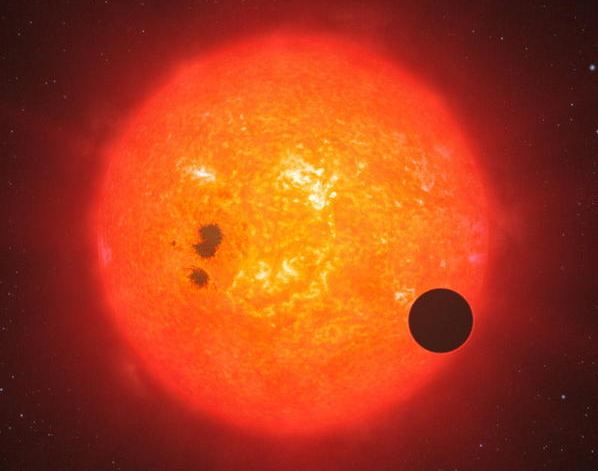

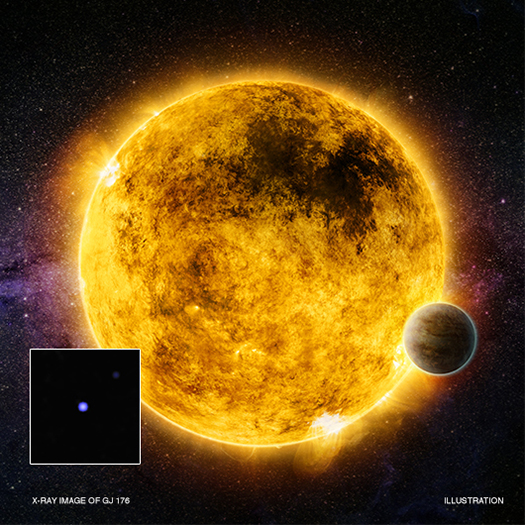

The most recent discovery was made by an international team of astronomers around Gliese 9827 (GJ 9827), a late K-type dwarf star located about 100 light-years from Earth. Using data provided by the K2 mission, they detected the presence of three Super-Earths. This star system is the closest exoplanet-hosting star discovered by K2 to date, which makes these planets well-suited for follow-up studies.

The study which describes their findings, titled “A System of Three Super Earths Transiting the Late K-Dwarf GJ 9827 at Thirty Parsecs“, was recently published online. Led by Dr. Jospeh E. Rodriguez from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), the team includes researchers from the University of Austin, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and the NASA Exoplanet Science Institute (NExSci) at Caltech.

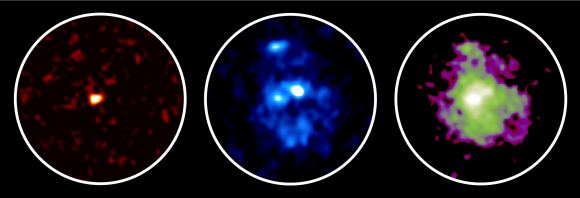

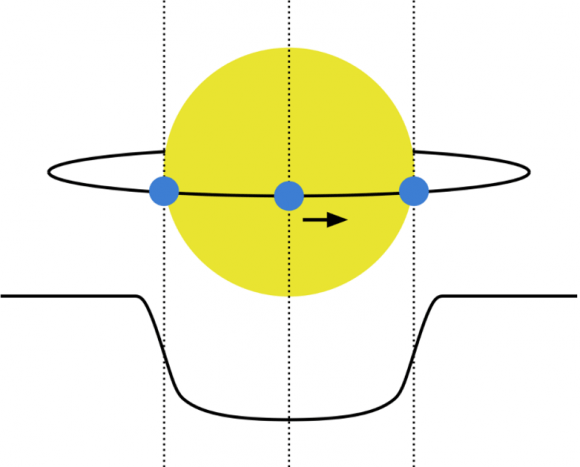

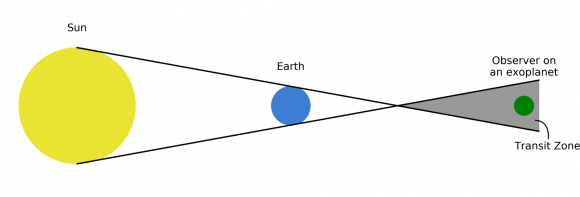

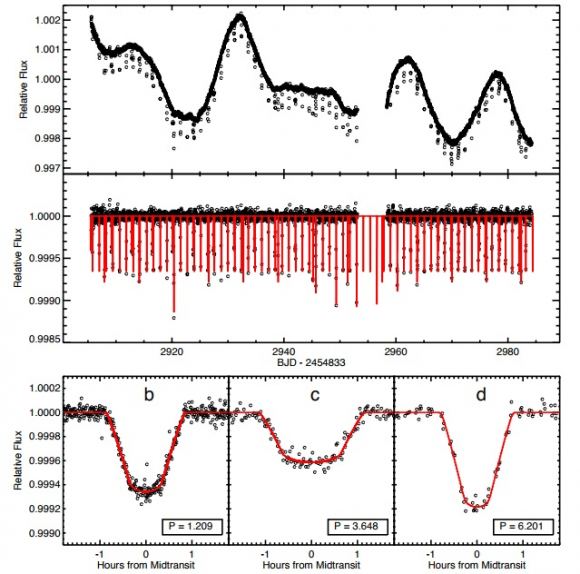

The Transit Method, which remains one of the most trusted means for exoplanet detection, consists of monitoring stars for periodic dips in brightness. These dips correspond to planets passing (aka. transiting) in front of the star causing a measurable drop in the light coming from it. This method also offers unique opportunities to examine light passing through an exoplanet’s atmosphere. As Dr. Rodriguez told Universe Today via email:

“The success of Kepler combined with ground based radial velocity and transit surveys has now led to the discovery of over 4000 planetary system. Since we now know that planets appear to be quite common, the field has shifted its focus to understand architectures, interior structures, and atmospheres. These key properties of planetary systems help us understand some fundamental questions: how do planets form and evolve? What are the terrestrial planets around other stars like, are they similar to Earth in composition and atmosphere?”

These questions were central to the team’s study, which relied on data obtained during Campaign 12 of the K2 mission – from December 2016 to March 2017. After consulting this data, the team noted the presence of three super-Earth sized planets orbiting in a very compact configuration. This system, as they note in their study, was independently and simultaneously discovered by another team from Wesleyan University.

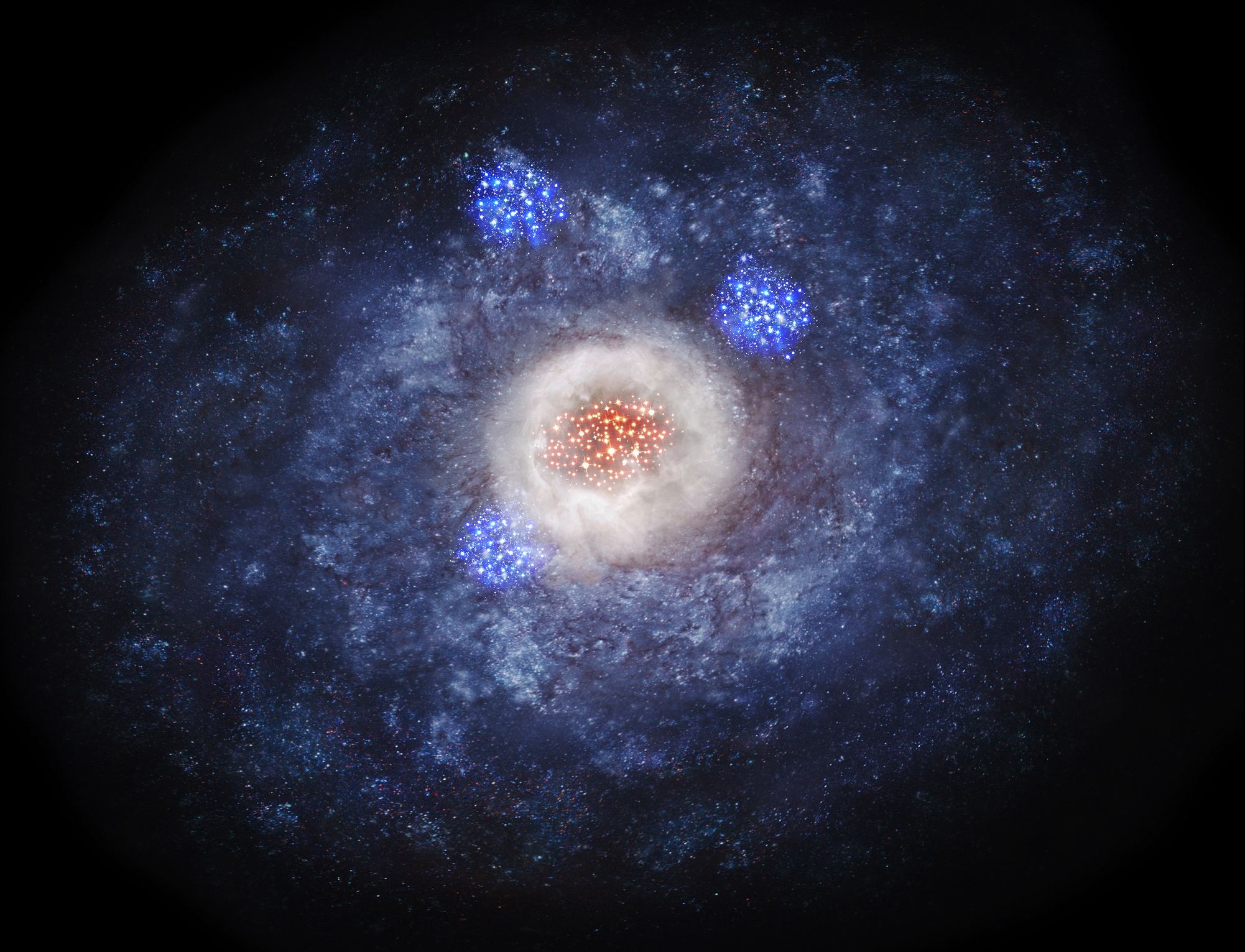

These three planetary objects, designated as GJ 9827 b, c, and d, are located at a distance of about 0.02, 0.04 and 0.06 AU from their host star (respectively). Owing to their sizes and radii, these planets are classified as “Super-Earths”, and have radii of 1.6, 1.2, and 2.1 times the radius of Earth. They are also located very close to their host star, completing orbits within 6.2 days.

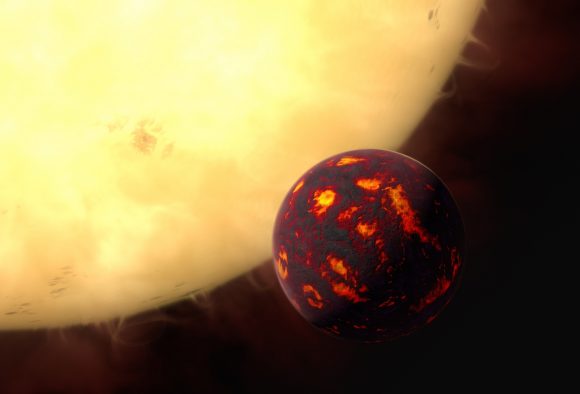

Specifically, GJ 9827 b measures 1.64 Earth radii, has a mass of up to 4.25 Earth masses, a 1.2 day orbital period, and a temperature of 1,119 K (846 °C; 1555 °F). Meanwhile, GJ 9827 c measures 1.29 Earth radii, has a mass of 2.62 Earth masses, an orbital period of 3.6 days, and a temperature of 774 K (500 °C; 934°F). Lastly, GJ 9827 d measures 2.08 Earth radii, has a mass of 5.3 Earth masses, a 6.2 day period, and a temperature of 648 K (375 °C; 707 °F).

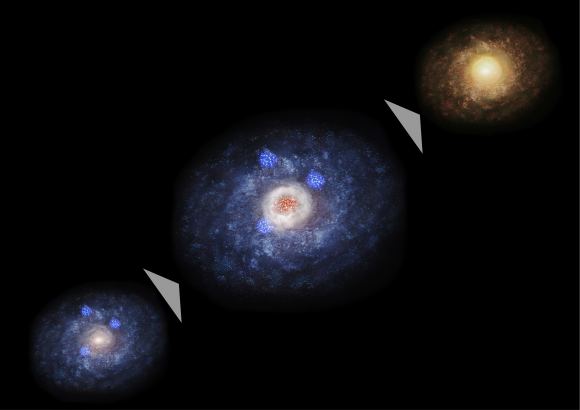

In short, all three planets are very hot, with temperatures that are hot as Venus and Mercury or (in the case of GJ 9827b) is even hotter! Interestingly, these radii and mass estimates place these planets within the transition boundary between terrestrial (i.e. rocky) planets and gas giants. In fact, the team found that GJ 9827 b and c fall in or close to the known gap in radius distribution for planets that are in between these two populations.

In other words, these planets could be rocky or gaseous, and the team won’t know for sure until they can place more accurate constraints on their masses. What’s more, none of these planets are likely to be capable of supporting life, certainly not as we know it! So if you were hoping that this latest find would produce an Earth-analog or potentially habitable planet, you’re sadly mistaken.

Nevertheless, the fact that these planets straddle the radius and mass boundary between terrestrial and gaseous planets – and the fact that this system is the closest planetary system to be identified by the K2 mission – makes the system well-situated for studies designed to probe the interior structure and atmosphere of exoplanets.

The reason for this has much to do with the brightness of the host star. In addition to being relatively close to our Sun (~100 light-years), this K-type star is very bright and also relatively small – about 60% the size of our Sun. As a result, any planet passing in front of it would be able to block out more light than if the star were larger. But as noted, there’s also the curious nature of the planets themselves. As Dr. Rodriguez indicated:

“Recently, we have found planets around other stars that have no analogue to a planet in our own system. These are known as “super Earths” and they have radii of 1-3 times the radius of the Earth. To add to the complexity of these planets, their is a clear dichotomy in their composition within this radius range. The larger super Earths (>1.6 x radius of the Earth) appear to be less dense, consistent with a puffy Hydrogen/Helium atmosphere. However, the smaller super Earths are more dense, consistent with an Earth-like composition (rock).

“As mentioned above, the GJ 9827 system hosts three super Earth sized planets. Interestingly, planet c has a radius consistent with it being rocky, planet d is consistent with being puffy, and planet b has a radius that is right on what we believe to be the transition boundary between rock and gas. Therefore, by studying the atmospheres of super-Earths, we may better understand the transition from dense rocky planets to puffier planets with very thick atmospheres (like Neptune).”

Looking ahead, the team hopes to conduct further studies to determine the masses of these planets more precisely. From this, they will be able to place better constraints on their compositions and determine if they are Super-Earths, mini gas giants, or some of each. Beyond that, they are to conduct more detailed studies of this system with next-generation instruments like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which is scheduled to launch in 2018.

“I am really interested in studying the atmosphere of GJ 9827 b, whether it is rocky or puffy,” said Dr. Rodriguez. “This planet has a radius at the rock/gas transition but it is very close to its host star. Therefore, by studying the chemical composition of its atmosphere we may better understand the impact of the host star’s proximity has on the evolution of its atmosphere. To do this we would use JWST to take spectroscopic observations during the transit of GJ 9827b (known as “Transmission Spectroscopy”). From this observations we will gather information on the chemical composition and extent of the planet’s atmosphere.“

Now that we have thousands of extra-solar planet discoveries under our belt, its only natural that research would be shifting towards trying to understand these planets better. In the coming years and decades, we are likely to learn volumes about the respective structures, compositions, atmospheres, and surface features of many distant worlds. One can only imagine what kind of things these studies will turn up!

Further Reading: arXiv