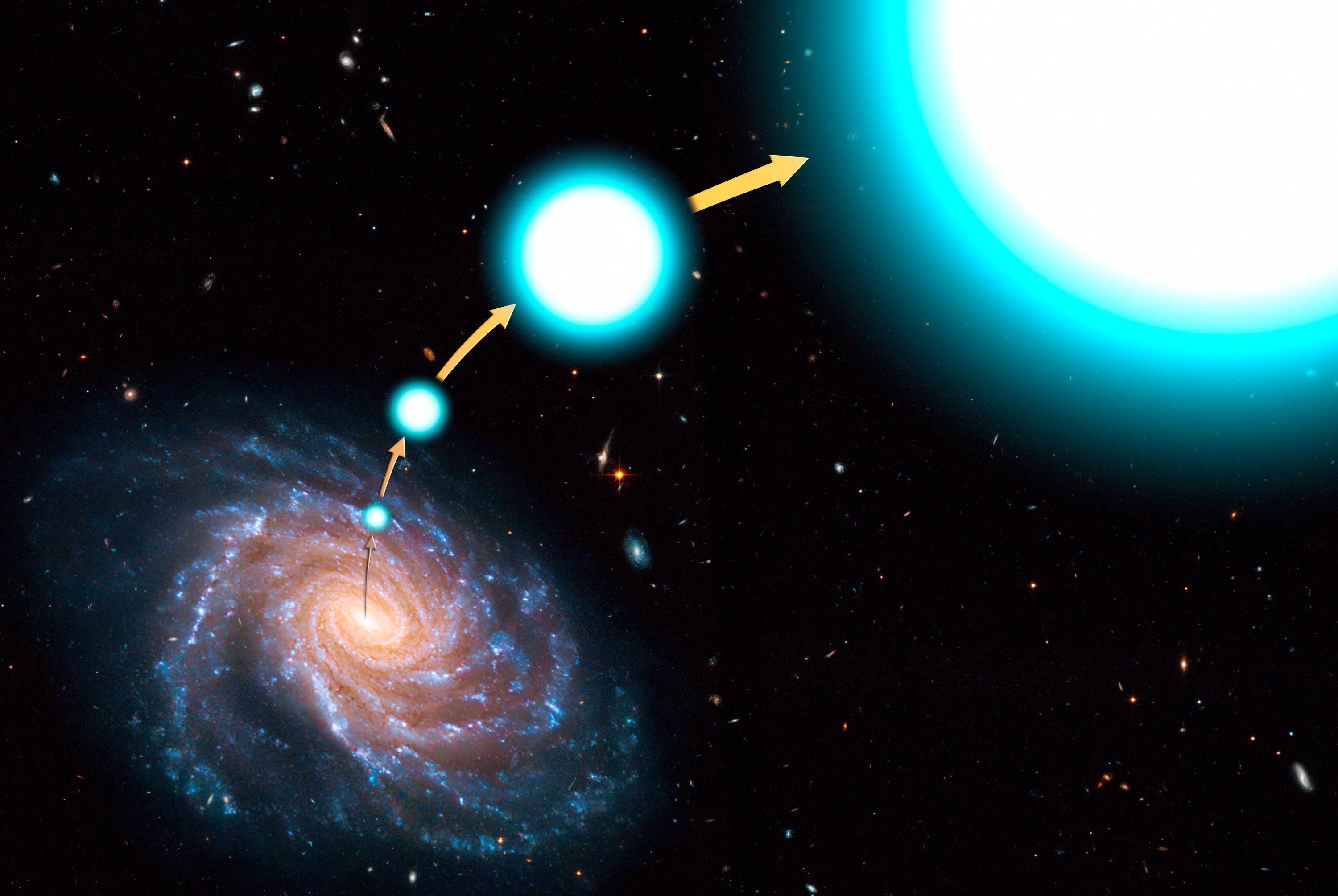

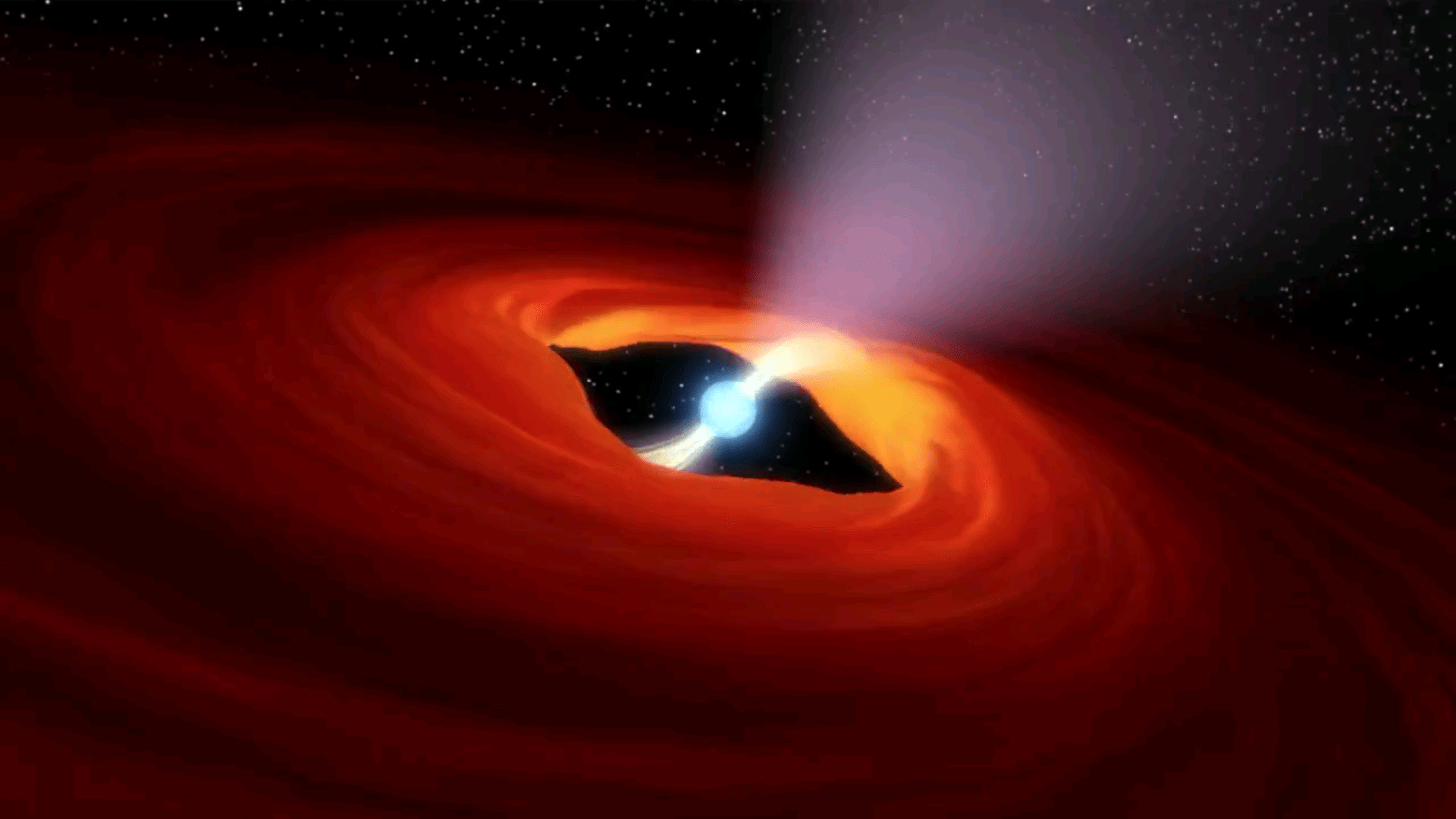

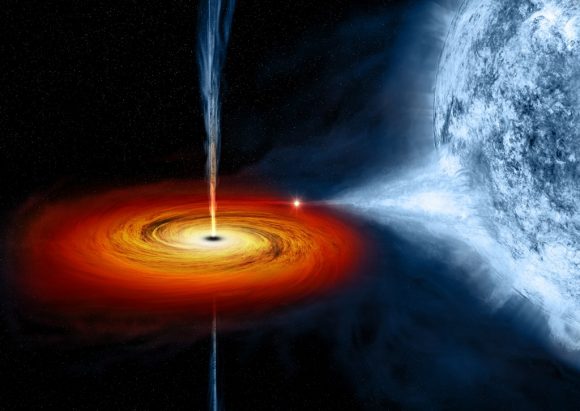

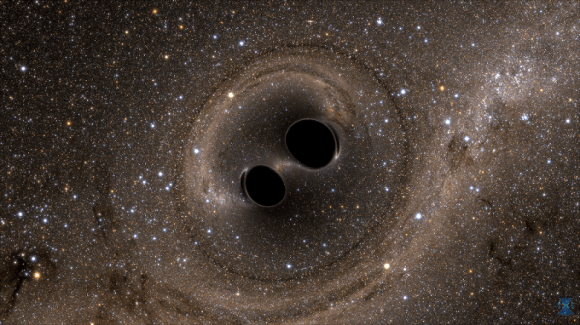

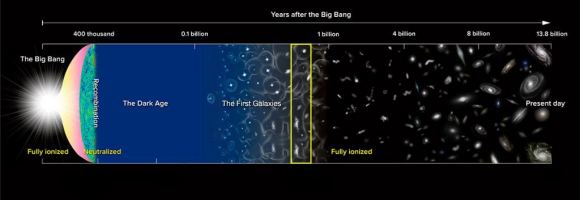

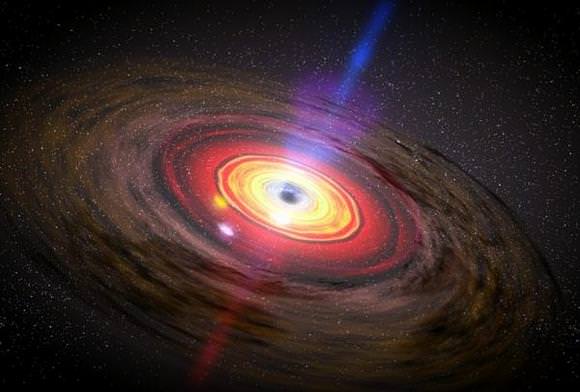

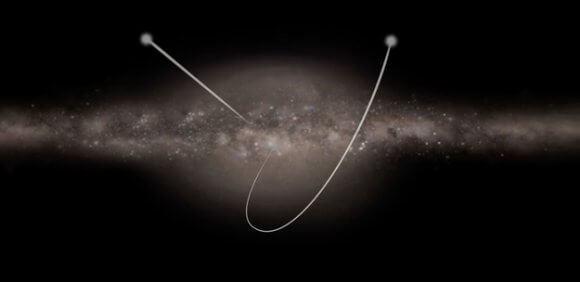

Most stars in our galaxy behave predictably, orbiting around the center of the Milky Way at speeds of about 100 km/s (62 mi/s). But some stars achieve velocities that are significantly greater, to the point that they are even able to escape the gravitational pull of the galaxy. These are known as hypervelocity stars (HVS), a rare type of star that is believed to be the result of interactions with a supermassive black hole (SMBH).

The existence of HVS is something that astronomers first theorized in the late 1980s, and only 20 have been identified so far. But thanks to a new study by a team of Chinese astronomers, two new hypervelocity stars have been added to that list. These stars, which have been designated LAMOST-HVS2 and LAMOST-HVS3, travel at speeds of up to 1,000 km/s (620 mi/s) and are thought to have originated in the center of our galaxy.

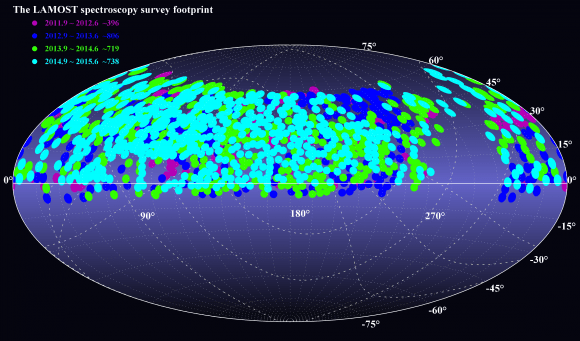

The study which describes the team’s findings, titled “Discovery of Two New Hypervelocity Stars From the LAMOST Spectroscopic Surveys“, recently appeared online. Led by Yang Huang of the South-Western Institute for Astronomy Research at Yunnan University in Kunming, China, the team relied on data from Large Sky Area Multi-Object Fibre Spectroscopic Telescope (LAMOST) to detect these two new hypervelocity stars.

Astronomers estimates that only 1000 HVS exist within the Milky Way. Given that there are as many as 200 billion stars in our galaxy, that’s just 0.0000005 % of the galactic population. While these stars are thought to originate in the center of our galaxy – supposedly as a result of interaction with our SMBH, Sagittarius A* – they manage to travel pretty far, sometimes even escaping our galaxy altogether.

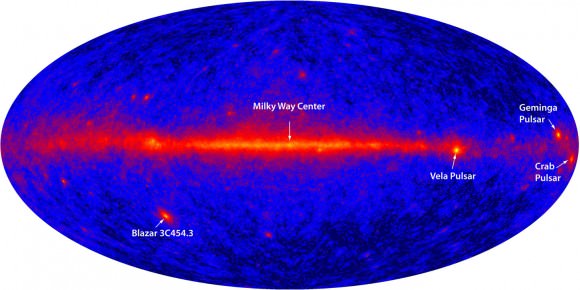

It is for this very reason that astronomers are so interested in HVS. Given their speed, and the vast distances they can cover, tracking them and creating a database of their movements could provide constraints on the shape of the dark matter halo of our galaxy. Hence why Dr. Huang and his colleagues began sifting through LAMOST data to find evidence of new HVS.

Located in Hebei Province, northwestern China, the LAMOST observatory is operated by the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Over the course of five years, this observatory conducted a spectroscopic survey of 10 million stars in the Milky Way, as well as millions of galaxies. In June of 2017, LAMOST released its third Data Release (DR3), which included spectra obtained during the pilot survey and its first three years’ of regular surveys.

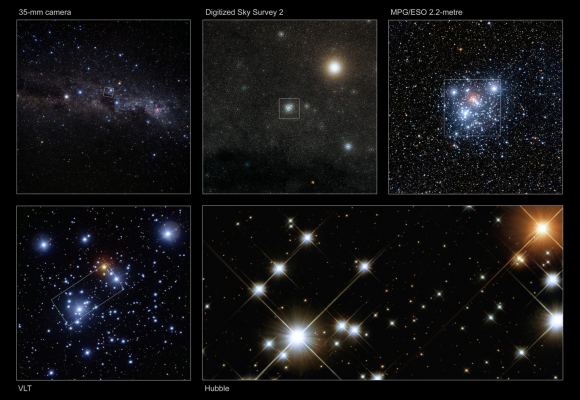

Containing high-quality spectra of 4.66 million stars and the stellar parameters of an additional 3.17 million, DR3 is currently the largest public spectral set and stellar parameter catalogue in the world. Already, LAMOST data had been used to identify one hypervelocity star, a B1IV/V-type (main sequence blue subgiant/subdwarf) star that was 11 Solar Masses, 13490 times as bright as our Sun, and had an effective temperature of 26,000 K (25,727 °C; 46,340 °F).

This HVS was designated LAMOST-HSV1, in honor of the observatory. After detecting two new HVSs in the LAMOST data, these stars were designated as LAMOST-HSV2 and LAMOST-HSV3. Interestingly enough, these newly-discovered HVSs are also main sequence blue subdwarfs – or a B2V-type and B7V-type star, respectively.

Whereas HSV2 is 7.3 Solar Masses, is 2399 times as luminous as our Sun, and has an effective temperature of 20,600 K (20,327 °C; 36,620 °F), HSV3 is 3.9 Solar Masses, is 309 times as luminous as the Sun, and has an effective temperature of 14,000 K (24,740 °C; 44,564 °F). The researchers also considered the possible origins of all three HVSs based on their spatial positions and flight times.

In addition to considering that they originated in the center of the Milky Way, they also consider alternate possibilities. As they state in their study:

“The three HVSs are all spatially associated with known young stellar structures near the GC, which supports a GC origin for them. However, two of them, i.e. LAMOST-HVS1 and 2, have life times smaller than their flight times, indicating that they do not have enough time to travel from the GC to the current positions unless they are blue stragglers (as in the case of HVS HE 0437-5439). The third one (LAMOST-HVS3) has a life time larger than its flight time and thus does not have this problem.

In other words, the origins of these stars is still something of a mystery. Beyond the idea that they were sped up by interacting with the SMBH at the center of our galaxy, the team also considered other possibilities that have suggested over the years.

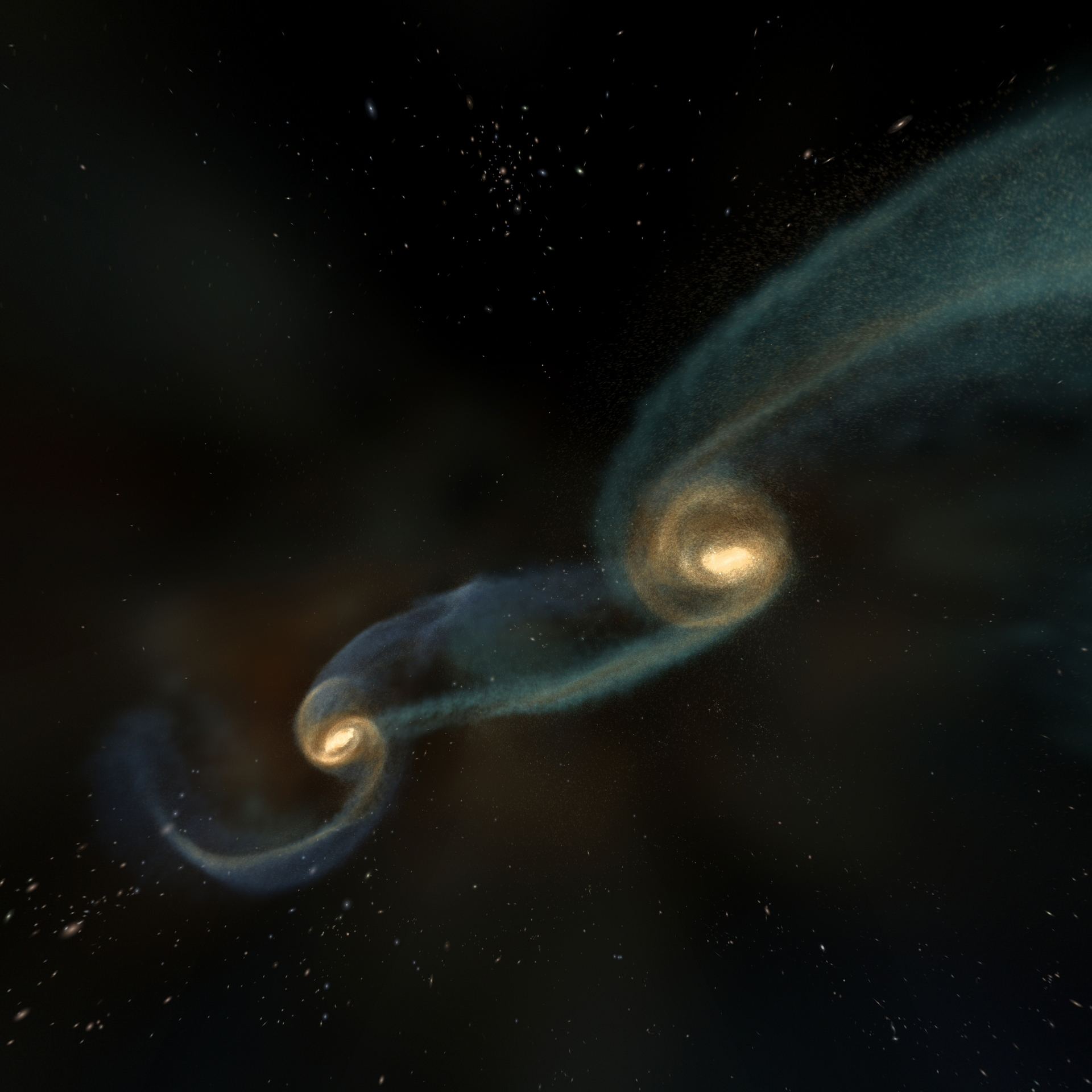

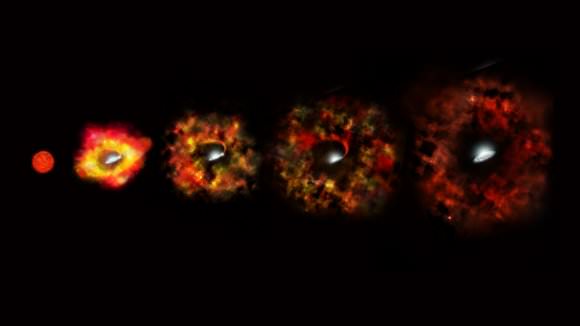

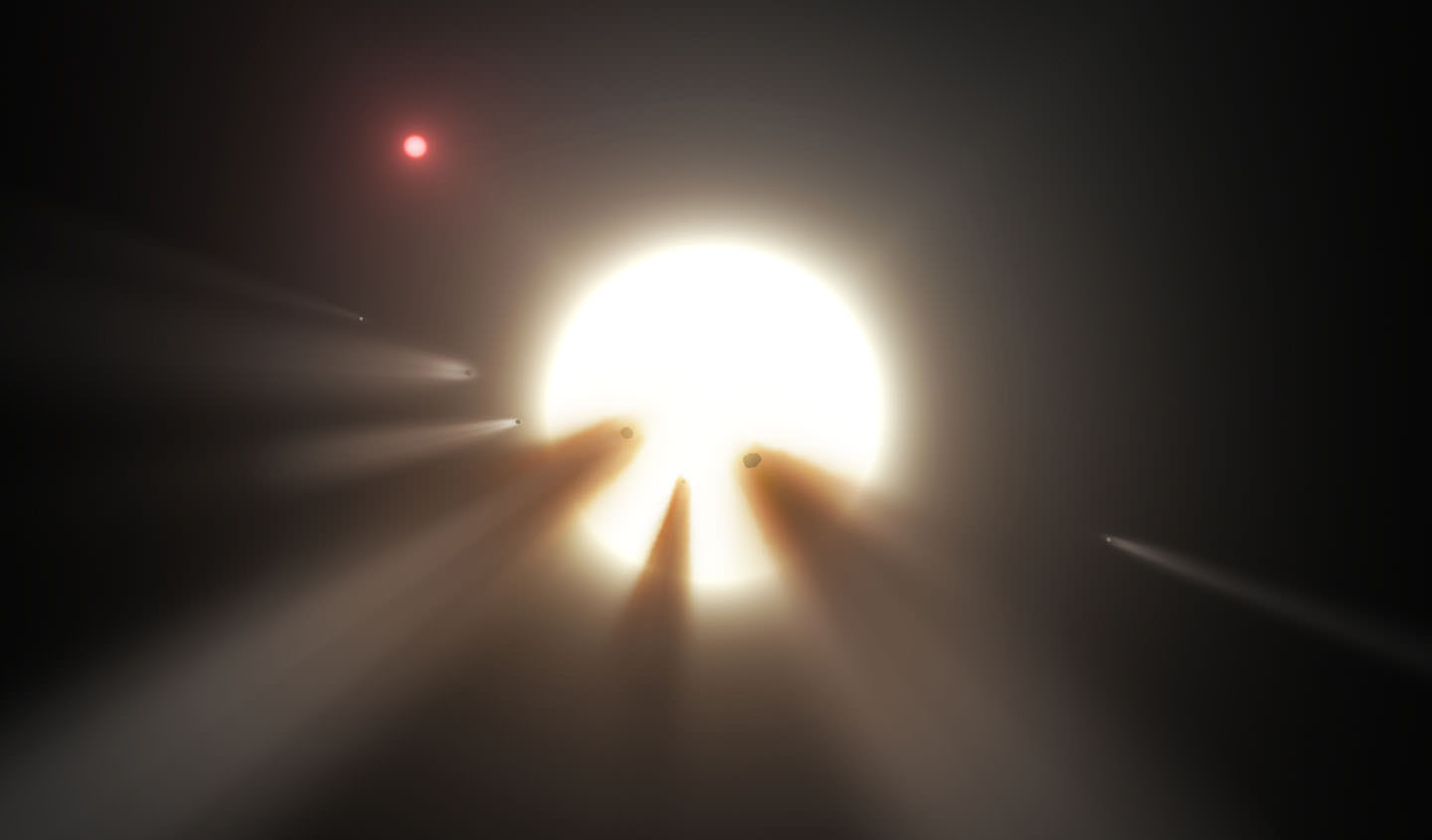

As they state in these study, these “include the tidal debris of an accreted and disrupted dwarf galaxy (Abadi et al. 2009), the surviving companion stars of Type Ia supernova (SNe Ia) explosions (Wang & Han 2009), the result of dynamical interaction between multiple stars (e.g, Gvaramadze et al. 2009), and the runaways ejected from the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), assuming that the latter hosts a MBH (Boubert et al. 2016).”

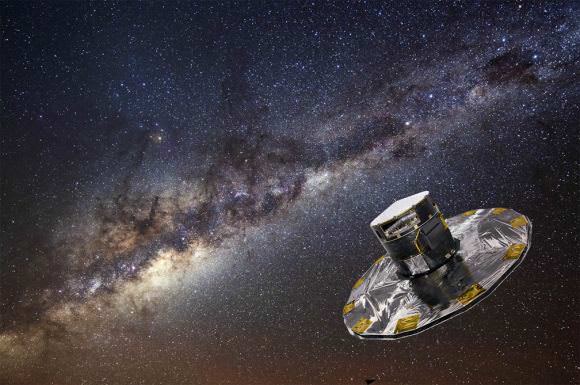

In the future, Huang and his colleagues indicate that their study will benefit from additional information that will be provided by the ESA’s Gaia mission, which they claim will shed additional light on how HVS behave and where they come from. As they state in their conclusions:

“The upcoming accurate proper motion measurements by Gaia should provide a direct constraint on their origins. Finally, we expect more HVSs to be discovered by the ongoing LAMOST spectroscopic surveys and thus to provide further constraint on the nature and ejection mechanisms of HVSs.”

Further Reading: arXiv