Long before the Apollo missions reached the Moon, Earth’s only satellites has been the focal point of intense interest and research. But thanks to the samples of lunar rock that were returned to Earth by the Apollo astronauts, scientists have been able to conduct numerous studies to learn more about the Moon’s formation and history. A key research goal has been determining how much volatile elements the Moon possesses.

Intrinsic to this is determining how much water the Moon possesses, and whether it has a “wet” interior. If the Moon does have abundant sources of water, it will make establishing outposts there someday much more feasible. However, according to a new study by an international team of researchers, the interior of the Moon is likely very dry, which they concluded after studying a series of “rusty” lunar rock samples collected by the Apollo 16 mission.

The study, titled “Late-Stage Magmatic Outgassing from a Volatile-Depleted Moon“, appeared recently in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Led by James M. D. Day of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, the team’s research was funded by the NASA Emerging Worlds program – which finances research into the Solar System’s formation and early evolution.

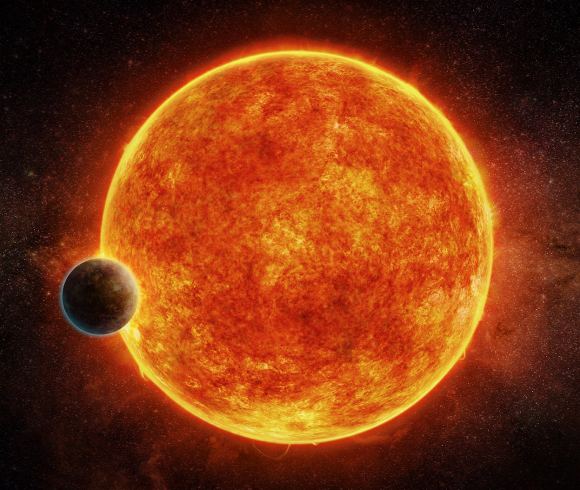

Determining how rich the Moon is in terms of volatile elements and compounds – such as zinc, potassium, chlorine, and water – is important because it provides insight into how the Moon and Earth formed and evolved. The most-widely accepted theory is that Moon is the result of “catastrophic formation”, where a Mars-sized object (named Theia) collided with Earth about 4.5 billion years ago.

The debris kicked up by this impact eventually coalesced to form the Moon, which then moved away from Earth to assume its current orbit. In accordance with this theory, the Moon’s surface would have been an ocean of magma during its early history. As a result, volatile elements and compounds within the Moon’s mantle would have been depleted, much in the same way that the Earth’s upper mantle is depleted of these elements.

As Dr. Day explained in a Scripps Institution press statement:

“It’s been a big question whether the moon is wet or dry. It might seem like a trivial thing, but this is actually quite important. If the moon is dry – like we’ve thought for about the last 45 years, since the Apollo missions – it would be consistent with the formation of the Moon in some sort of cataclysmic impact event that formed it.”

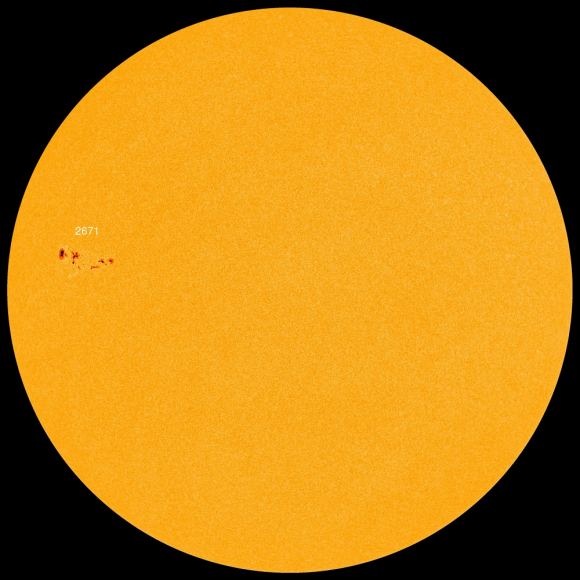

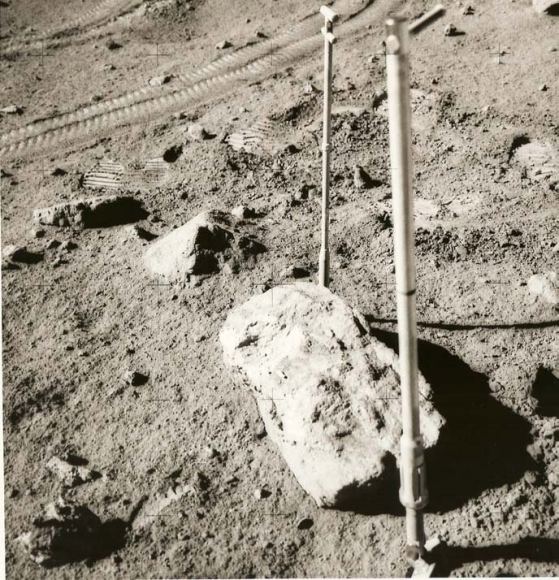

For the sake of their study, the team examined a lunar rock named “Rusty Rock 66095” to determine the volatile content of the Moon’s interior. These rocks have mystified scientists since they were first brought back by the Apollo 16 mission in 1972. Water is an essential ingredient to rust, which led scientists to conclude that the Moon must have an indigenous source of water – something which seemed unlikely, given the Moon’s extremely tenuous atmosphere.

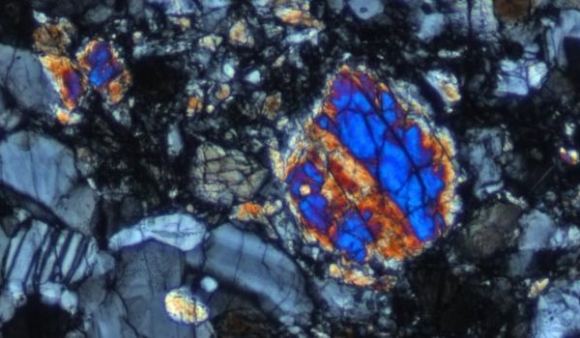

Using a new chemical analysis, Day and his colleagues determined the levels of istopically light zinc (Zn66) and heavy chlorine (Cl37), as well as the levels of heavy metals (uranium and lead) in the rock. Zinc was the key element here, since it is a volatile element that would have behaved somewhat like water under the extremely hot conditions that were present during the Moon’s formation.

Ultimately, the supply of volatiles and heavy metals in the sample support the theory that volatile enrichment of the lunar surface occurred as a result of vapor condensation. In other words, when the Moon’s surface was still an ocean of hot magma, its volatiles evaporated and escaped from the interior. Some of these then condensed and were deposited back on the surface as it cooled and solidified.

This would explain the volatile-rich nature of some rocks on the lunar surface, as well as the levels of light zinc in both the Rusty Rock samples and the previously-studied volcanic glass beads. Basically, both were enriched by water and other volatiles thanks to extreme outgassing from the Moon’s interior. However, these same conditions meant that most of the water in the Moon’s mantle would have evaporated and been lost to space.

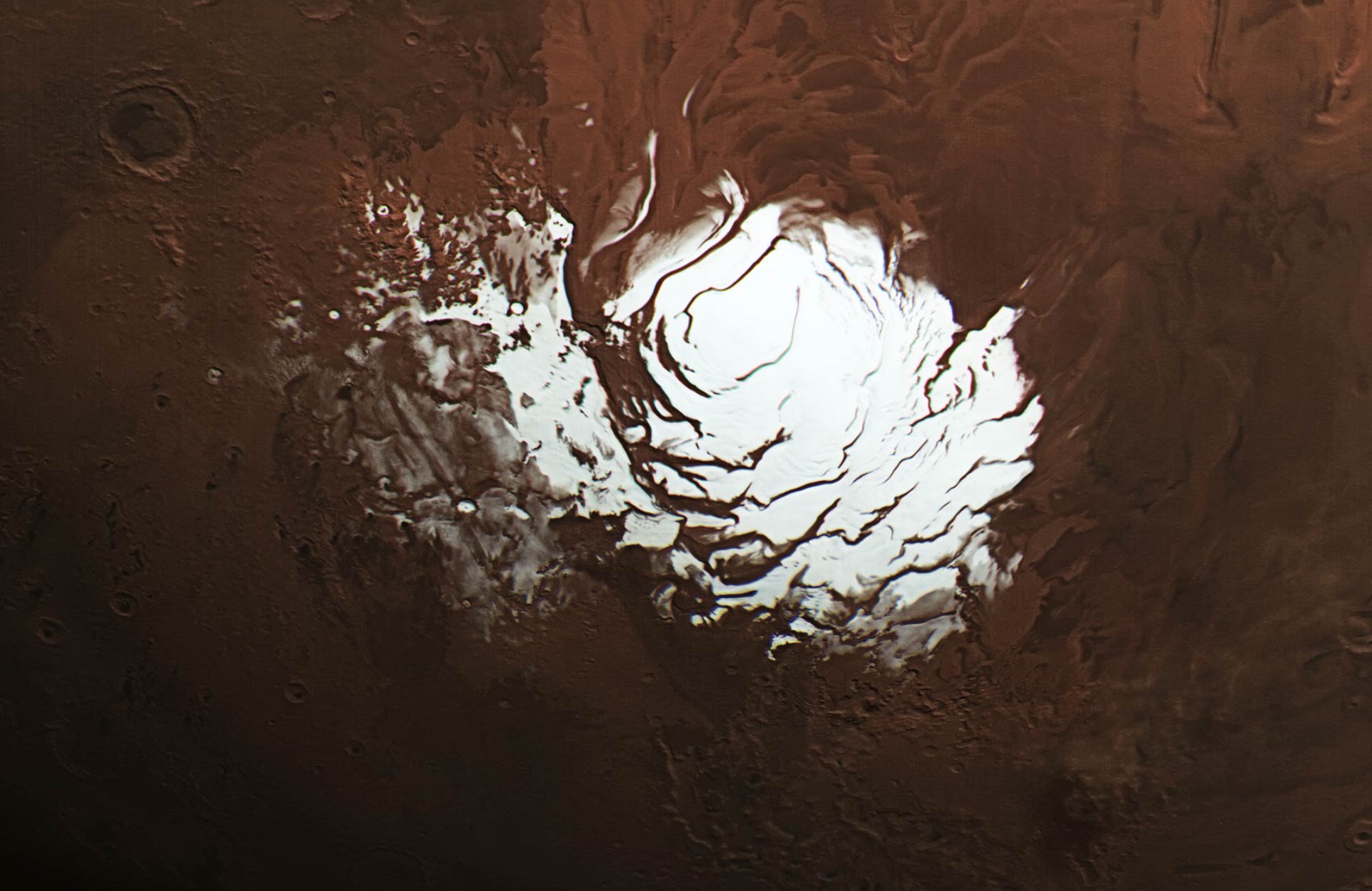

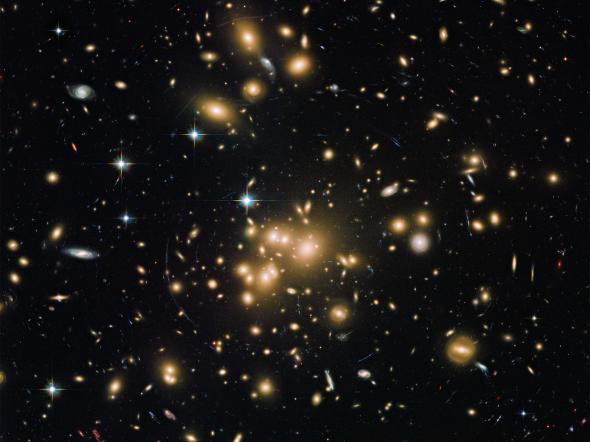

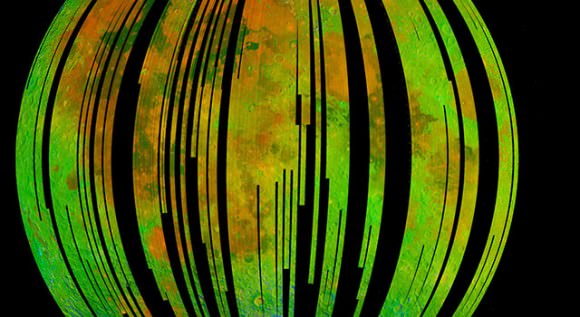

Image credit: ISRO/NASA/JPL-Caltech/Brown Univ./USGS

This represents something of a paradox, in that it shows how rocks that contain water were formed in a very dry, interior part of the Moon. However, as Day indicated, it offers a sound explanation for an enduring lunar mystery:

“I think the Rusty Rock was seen for a long time as kind of this weird curiosity, but in reality, it’s telling us something very important about the interior of the moon. These rocks are the gifts that keep on giving because every time you use a new technique, these old rocks that were collected by Buzz Aldrin, Neil Armstrong, Charlie Duke, John Young, and the Apollo astronaut pioneers, you get these wonderful insights.”

These results contradict other studies that suggest the Moon’s interior is wet, one of which was recently conducted by researchers at Brown University. By combining data provided by Chandrayaan-1 and the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) with new thermal profiles, the Brown research team concluded that lots of water exists within volcanic deposits on the Moon’s surface, which could also mean there are vast quantities of water in the Moon’s interior.

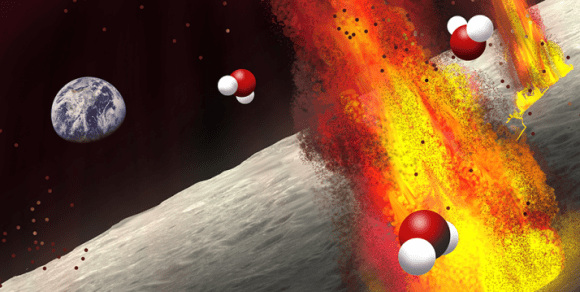

To these, Day emphasized that while these studies present evidence that water exists on the lunar surface, they have yet to offer a solid explanation for what mechanisms deposited it on the surface. Day and his colleague’s study also flies in the face of other recent studies, which claim that the Moon’s water came from an external source – either by comets which deposited it, or from Earth during the formation of the Earth-Moon system.

Those who believe that lunar water was deposited by comets cite the similarities between the ratios of hydrogen to deuterium (aka. “heavy hydrogen”) in both the Apollo lunar rock samples and known comets. Those who believe the Moon’s water came from Earth, on the other hand, point to the similarity between water isotopes on both the Moon and Earth.

In the end, future research is needed to confirm where all of the Moon’s water came from, and whether or not it exists within the Moon’s interior. Towards this end, one of Day’s PhD students – Carrie McIntosh – is conducting her own research into the lunar glass beads and the composition of the deposits. These and other research studies ought to settle the debate soon enough!

And not a moment too soon, considering that multiple space agencies hope to build a lunar outpost in the upcoming decades. If they hope to have a steady supply of water for creating hydrazene (rocket fuel) and growing plants, they’ll need to know if and where it can be found!

Further Reading: UC San Diego, PNAS