Welcome to another edition of Constellation Friday! Today, in honor of the late and great Tammy Plotner, we take a look at the “Raven” – the Corvus constellation. Enjoy!

In the 2nd century CE, Greek-Egyptian astronomer Claudius Ptolemaeus (aka. Ptolemy) compiled a list of all the then-known 48 constellations. This treatise, known as the Almagest, would be used by medieval European and Islamic scholars for over a thousand years to come, effectively becoming astrological and astronomical canon until the early Modern Age.

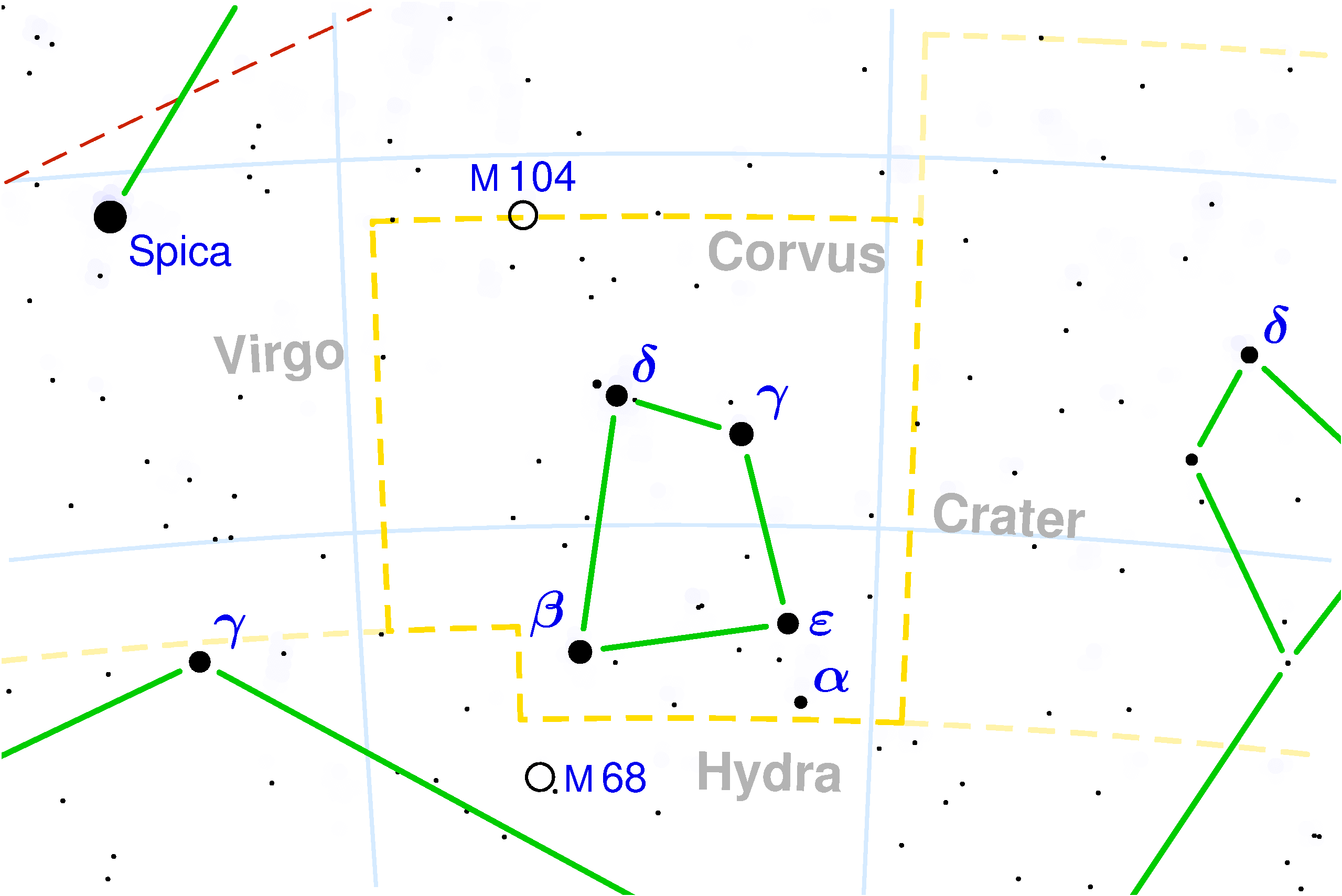

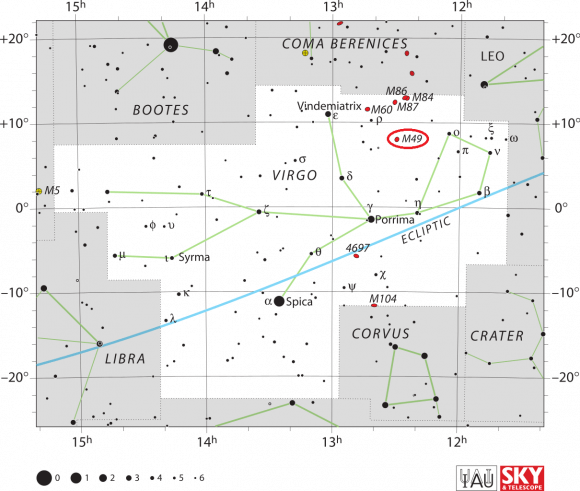

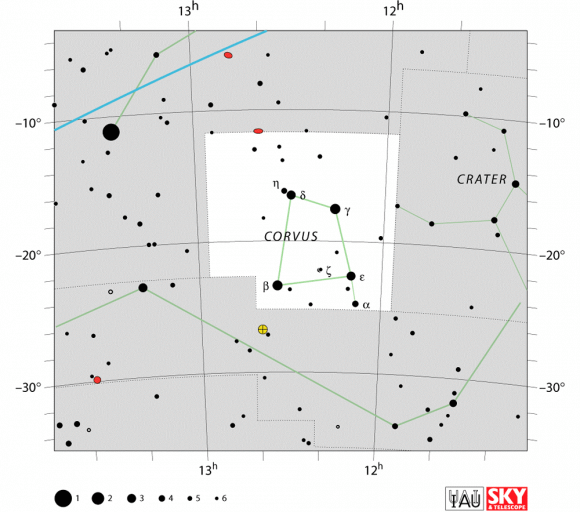

One of these constellation is the Corvus constellation, a southern constellation whose name in Latin means “the Raven”. Bordered by the constellations of Virgo, Crater and Hydra, it is visible at latitudes between +60° and -90° and is best seen at culmination during the month of May. Today, it is one of the 88 modern constellations recognized by the International Astronomical Union (IAU).

Name and Meaning:

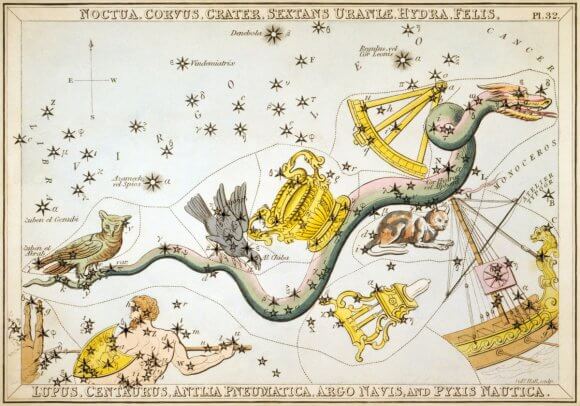

In classical mythology, Corvus represents the Raven, and is both a charming and sad tale. Legend tells us that the constellation of Crater is the cup of the gods. This cup belonged to the god of the skies himself, the venerable archer-god Apollo. And who holds this cup, dressed in black? The Raven, Corvus.

The story of a creature sent to fetch water for his master, only to stop to eat figs. Corvus tarried too long, waiting on a fig to ripen. When he realized his mistake, the Raven returned to Apollo with his cup and brought along the serpent Hydra in his claws as well, claiming that the snake prevented him from filling the cup.

Realizing his feathered-friend’s lie, Apollo became angry and tossed the cup (Crater), the snake (Hydra) and the raven (Corvus) into the sky, where they became constellations for all eternity. He further punished the raven by making sure the cup would be out of reach, thus ensuring he would forever be thirsty.

History of Observation:

As with most of the 48 constellations recorded by Ptolemy, the Corvus constellation has roots that go back to ancient Mesopotamia. In the Babylonian star catalogues (dated to ca. 1100 BCE), Corvus was called the Babylonian Raven (MUL.UGA.MUSHEN), which sat on the tail of the Serpent – which was associated with Ningishzida, the Babylonian god of the underworld. This constellation was also sacred to the god of rains and storm (Adad).

By about 500 BCE, this constellation was introduced to the Greeks, along with Crater, Hydra, Aquila and Piscis Austrinus constellations. By the 2nd century CE, they were included by Ptolemy in his Almagest, which would remain the definitive source on astronomy and astrology to Medieval European and Islamic astronomers for many centuries.

In Chinese astronomy, the stars that make up Corvus are located within the Vermilion Bird of the South (Nán Fang Zhu Què). The four main stars depict a chariot (Zhen) while Alpha and Eta mark the linchpins for the wheels, and Zeta represents a coffin (Changsha).

In Indian astronomy, the first five stars in Corvus correspond to the Hast nakshatra – a lunar zodiacal constellation. This is one of is one of the 27 or 28 divisions of the sky, identified by the prominent stars in them, that the Moon passes through during its monthly cycle. While it is Hindu, it is still very similar to the divisions of the ecliptic plane referred to as the zodiac. The Moon takes approximately one day to pass through each nakshatra.

Notable Objects:

This small, box-like asterism has no bright star and consists of 11 stars which are visible to the unaided eye, yet Ptolemy only listed 7! There are 4 main stars and 10 which have Bayer/Flamsteed designations. For unaided eye observers, the Delta, Gamma, Epsilon and Beta (what appears to look like a figure 8, Y, E and B on the map) form an asterism that looks like a “sail”, and when connected seem to point to the bright star Spica.

The brightest star in Corvus is not even its alpha, but is Gamma Corvi. This giant star (which is thought to be a binary system) is located approximately 165 light years from Earth and is also known as Gienah, which comes from the Arabic phrase al-janah al-ghirab al-yaman (“the right wing of the crow”).

The second-brightest star, Beta Corvi, is a yellow-white G-type bright giant that is located about 140 light years from Earth. Its proper name, Kraz, was assigned to it in modern times, but the origin of the name is uncertain. Delta Corvi is a class A0 star in Corvus located approximately 87 light years distant from Earth whose traditional name (Algorab) comes from the Arabic word al-ghuraab – which means “the crow.”

Epsilon Corvi is a K2 III class star that is approximately 303 light-years from Earth. The star’s traditional name, (Minkar) comes from the Arabic word almánxar, which means “the nostril of the crow.” Alpha Corvi, which is only the fifth brightest star in the constellation, is a class F0 dwarf or subdwarf that is only 48.2 light years distant. The star’s traditional name (Alchiba) is derived from the Arabic al hibaa, which means “tent.”

Corvus is also home to many Deep Sky Objects. These include the Antennae Galaxies (NGC 4038/NGC 4039), a pair of interacting galaxies that were first discovered in the late 18th century. These colliding galaxies – which are located 45 million light years from Earth – are currently in the starburst stage, meaning they are experiencing an exceptionally high rate of star forming activity.

There’s also the NGC 4027 barred spiral galaxy, which is located about 83 million light years from Earth. This galaxy is peculiar, in that one of its spiral arm extends further than the other – possibly due to a past collision with another galaxy. Finally, there’s the large planetary nebula known as NGC 4361, which is located at the center of the constellation and resembled a faint elliptical galaxy.

Finding Corvus:

Let’s start with binoculars and look down at the southern corner, where we will find Alpha Corvi – aka. Alchiba. Alchiba belongs to the spectral class F0 and has apparent magnitude +4.00. This star is suspected of being a spectroscopic binary, although this has not yet been confirmed. Now take a look at Beta Corvi – aka. Kraz. Good old Kraz is approximately 140 light-years away and is a G-type bright giant star whose apparent visual magnitude varies between 2.60 and 2.66.

Head west and look at Epsilon. Although it doesn’t look any further away, spectral class K2 III – Minkar – is 303 light-years from Earth! Need a smile? Then take a look at Gamma, aka. Geinah. How about Delta? Algorab is a spectral class A0 and is about 87 light years from our solar system.

Now get out your telescope as we explore planetary nebula, NGC 4361 (RA 12 24 5 Dec -18 48). At around magnitude 10, this greenish disc is fairly easily spotted with smaller telescopes, but the 13th stellar magnitude central star requires larger aperture to be seen. It has a very symmetrical shape that is similar to a spiral galaxy.

For galaxy fans, have a look at interacting galaxy pair, NGC 4038 and NGC 4039 – the “Ringtail Galaxy” (RA 12 01 53 Dec -18 52-3). This peculiar galaxy (also referred to as the “Antennae Galaxies”) were both discovered by Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel in 1785. Even in relatively small telescopes, you can see two long tails of stars, gas and dust thrown out of the galaxies as a result of the collision that resemble the antennae of an insect.

As explained by Vázquez (et al.) in a 1999 study:

“The morphology of this object is complex given the highly filamentary structure of the envelope, which is confirmed to possess a low mass. The halo has a high expansion velocity that yields incompatible kinematic and evolutionary ages, unless previous acceleration of the nebular expansion is considered. However, the most remarkable result from the present observations is the detection of a bipolar outflow in NGC 4361, which is unexpected in a PN with a Population II low-mass-core progenitor. It is shown that shocks resulting from the interaction of the bipolar outflow with the outer shell are able to provide an additional heating source in this nebula.”

Most galaxies probably undergo at least one significant collision in their lifetimes. This is likely the future of our Milky Way when it collides with the Andromeda Galaxy. Two supernovae have been discovered in the galaxy: SN 2004GT and SN 2007sr. A recent study finds that these interacting galaxies are closer to the Milky Way than previously thought – at 45 million light-years instead of 65 million light-years. Geez… What’s 20 million light years between friends?

We have written many interesting articles about the constellation here at Universe Today. Here is What Are The Constellations?, What Is The Zodiac?, and Zodiac Signs And Their Dates.

Be sure to check out The Messier Catalog while you’re at it!

For more information, check out the IAUs list of Constellations, and the Students for the Exploration and Development of Space page on Canes Venatici and Constellation Families.

Sources: