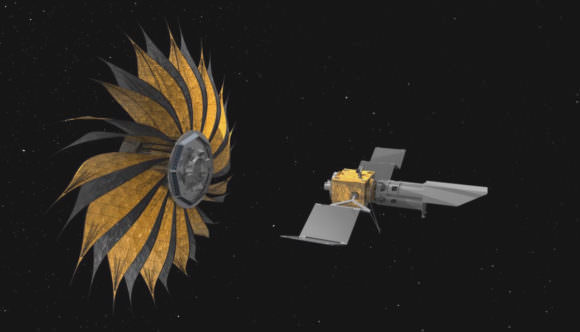

NASA has turned a lot of heads in recent years thanks to its New Worlds Mission concept – aka. Starshade. Consisting of a giant flower-shaped occulter, this proposed spacecraft is intended to be deployed alongside a space telescope (most likely the James Webb Space Telescope). It will then block the glare of distant stars, creating an artificial eclipse to make it easier to detect and study planets orbiting them.

The only problem is, this concept is expected to cost a pretty penny – an estimated $750 million to $3 billion at this point! Hence why Stanford Professor Simone D’Amico (with the help of exoplanet expert Bruce Macintosh) is proposing a scaled down version of the concept to demonstrate its effectiveness. Known as mDot, this occulter will do the same job, but at a fraction of the cost.

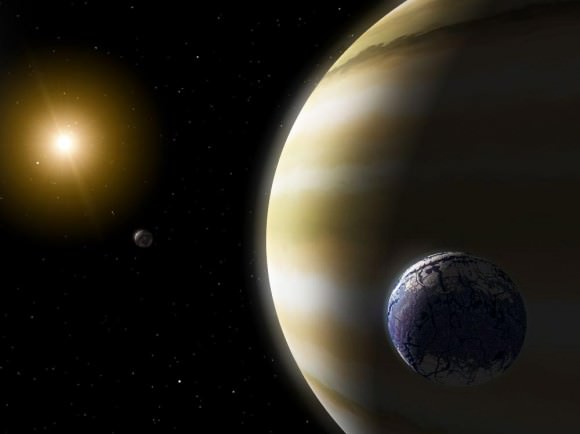

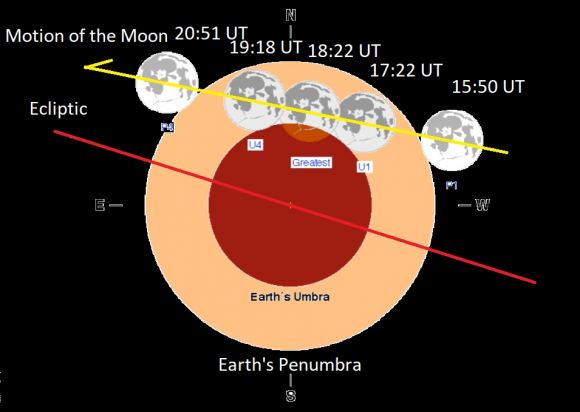

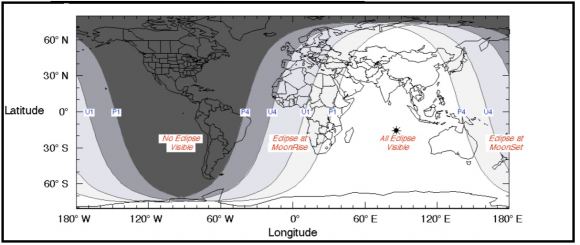

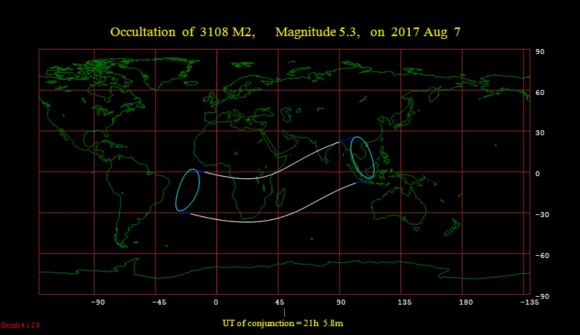

The purpose behind an occulter is simple. When hunting for exoplanets, astronomers are forced to rely predominantly on indirected methods – the most common being the Transit Method. This involves monitoring stars for dips in luminosity, which are attributed to planets passing between them and the observer. By measuring the rate and the frequency of these dips, astronomers are able to determine the sizes of exoplanets and their orbital periods.

As Simone D’Amico, whose lab is working on this eclipsing system, explained in a Stanford University press statement:

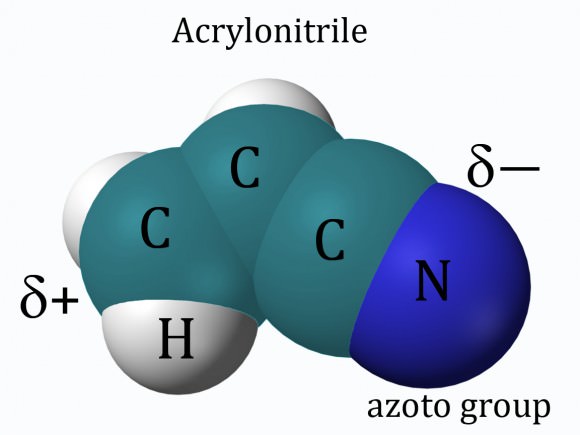

“With indirect measurements, you can detect objects near a star and figure out their orbit period and distance from the star. This is all important information, but with direct observation you could characterize the chemical composition of the planet and potentially observe signs of biological activity – life.”

However, this method also suffers from a substantial rate of false positives and generally requires that part of the planet’s orbit intersect a line-of-sight between the host star and Earth. Studying the exoplanets themselves is also quite difficult, since the light coming from the star is likely to be several billion times brighter than the light being reflected off the planet.

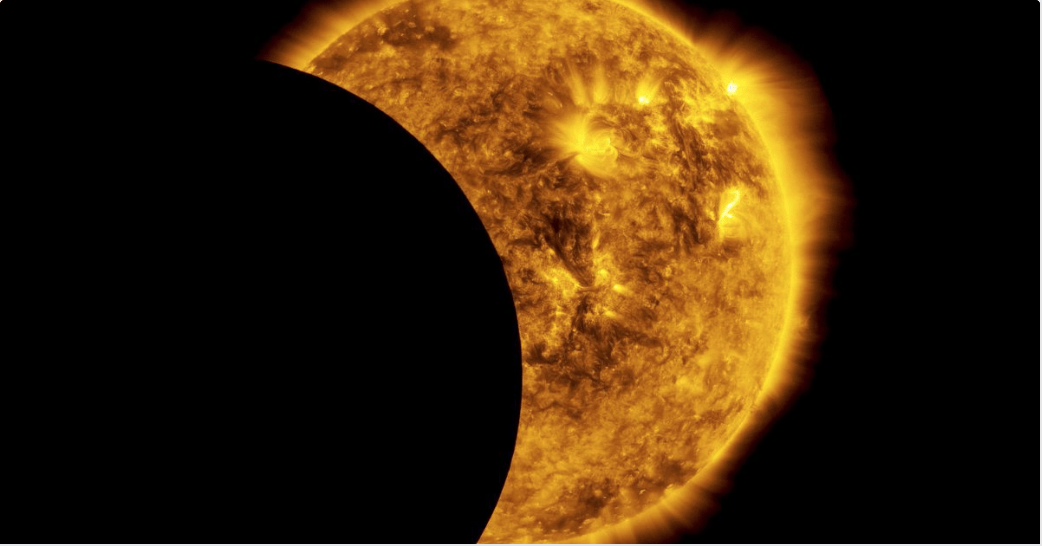

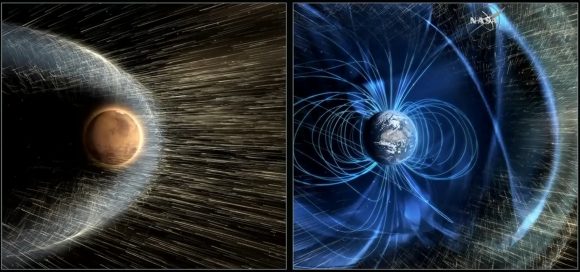

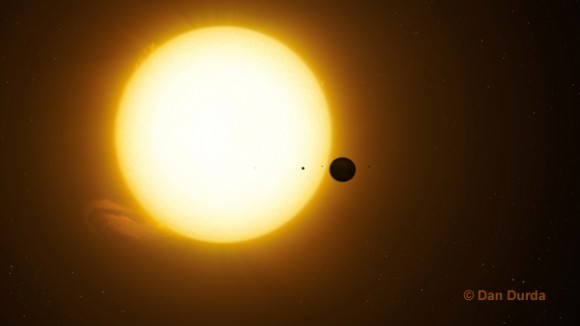

The ability to study this reflected light is of particular interest, since it would yield valuable data about the exoplanets’ atmospheres. As such, several key technologies are being developed to block out the interfering light of stars. A spacecraft equipped with an occulter is one such technology. Paired with a space telescope, this spacecraft would create an artificial eclipse in front of the star so objects around it (i.e. exoplanets) can be clearly seen.

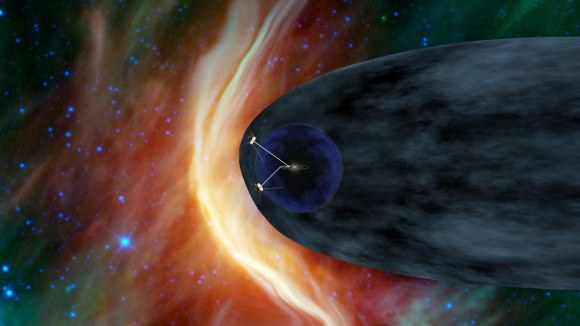

But in addition to the significant cost of building one, there is also the issue of size and deployment. For such a mission to work, the occulter itself would need to be about the size of a baseball diamond – 27.5 meters (90 feet) in diameter. It would also need to be separated from the telescope by a distance equal to multiple Earth diameters and would have to be deployed beyond Earth’s orbit. All of this adds up to a rather pricey mission!

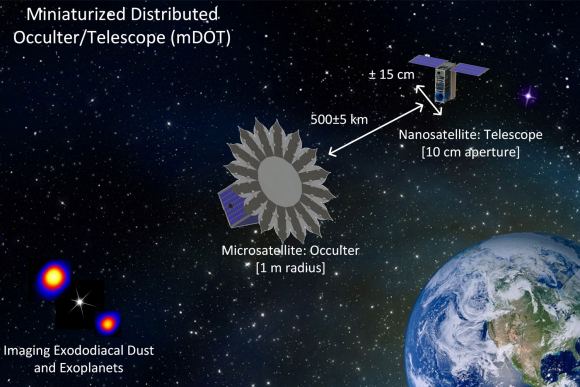

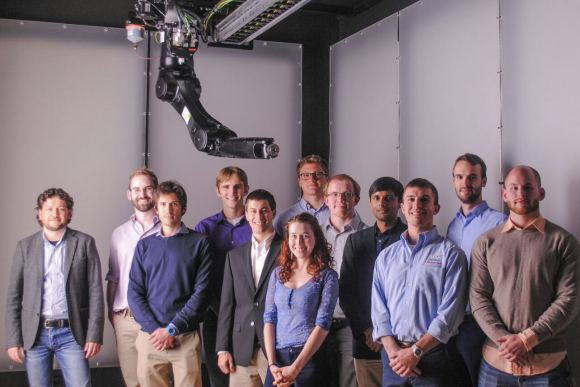

As such, D’Amico – an assistant professor and the head of the Space Rendezvous Laboratory (SRL) at Stanford – and and Bruce Macintosh (a Stanford professor of physics) teamed up to create a smaller version called the Miniaturized Distributed Occulter/Telescope (mDOT). The primary purpose of mDOT is to provide a low-cost flight demonstration of the technology, in the hopes of increasing confidence in a full-scale mission.

As Adam Koenig, a graduate student with the SRL, explained:

“So far, there has been no mission flown with the degree of sophistication that would be required for one of these exoplanet imaging observatories. When you’re asking headquarters for a few billion dollars to do something like this, it would be ideal to be able to say that we’ve already flown all of this before. This one is just bigger.”

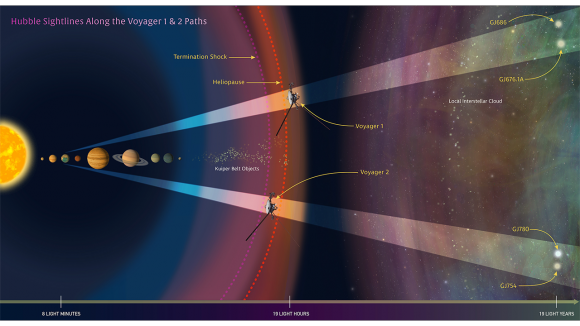

Consisting of two parts, the mDOT system takes advantage of recent developments in miniaturization and small satellite (smallsat) technology. The first is a 100-kg microsatellite that is equipped with a 3-meter diameter starshade. The second is a 10-kg nanosatellite that carries a telescope measuring 10 cm (3.937 in) in diameter. Both components will be deployed in high Earth orbit with a nominal separation of less than 1,000 kilometers (621 mi).

With the help of colleagues from the SRL, the shape of mDOT’s starshade was reformulated to fit the constraints of a much smaller spacecraft. As Koenig explained, this scaled down and specially-designed starshade will be able to do the same job as the large-scale, flower-shaped version – and on a budget!

“With this special geometric shape, you can get the light diffracting around the starshade to cancel itself out,” he said. “Then, you get a very, very deep shadow right in the center. The shadow is deep enough that the light from the star won’t interfere with observations of a nearby planet.”

However, since the shadow created by mDOT’s starshade is only tens of centimeters in diameter, the nanosatellite will have do some careful maneuvering to stay within it. For this purpose, D’Amico and the SRL also designed an autonomous system for the nanosatellite, which would allow it to conduct formation maneuvers with the starshade, break formation when needed, and rendezvous with it again later.

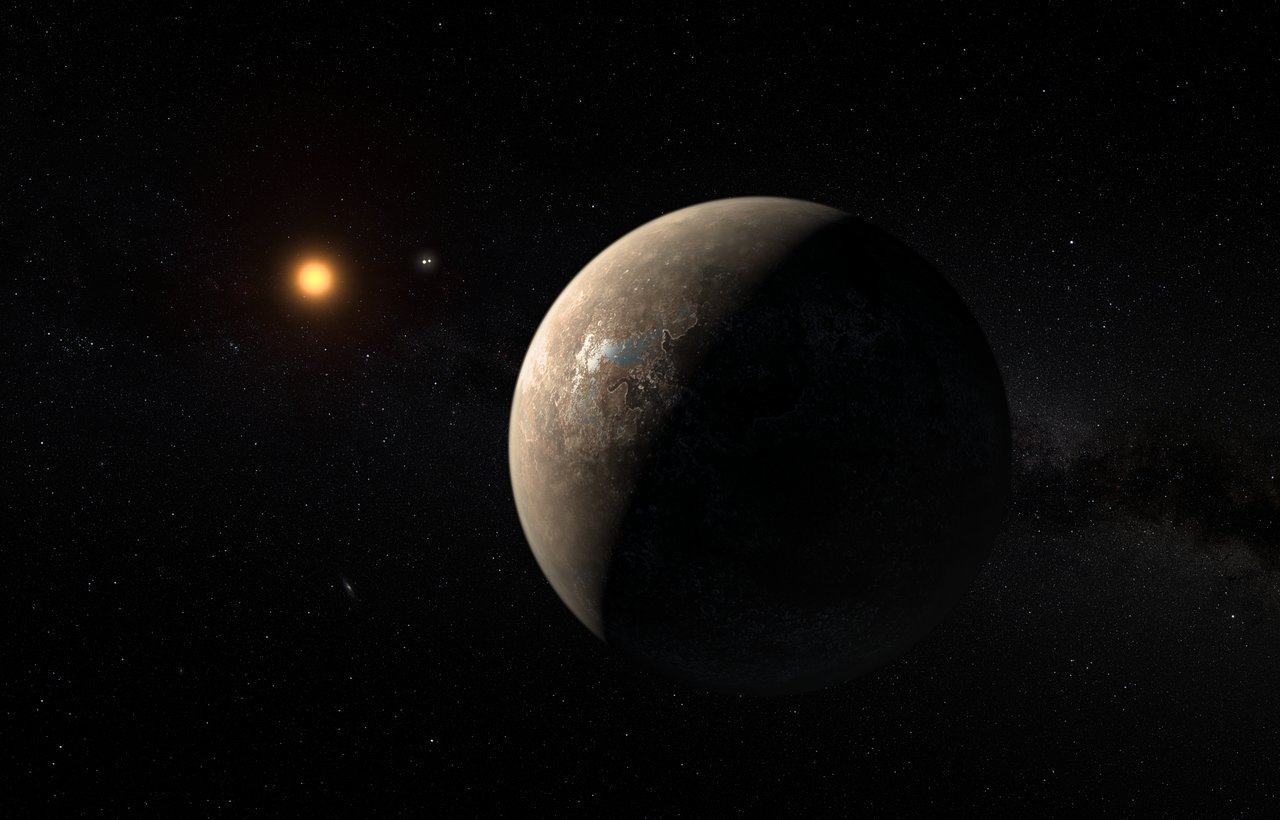

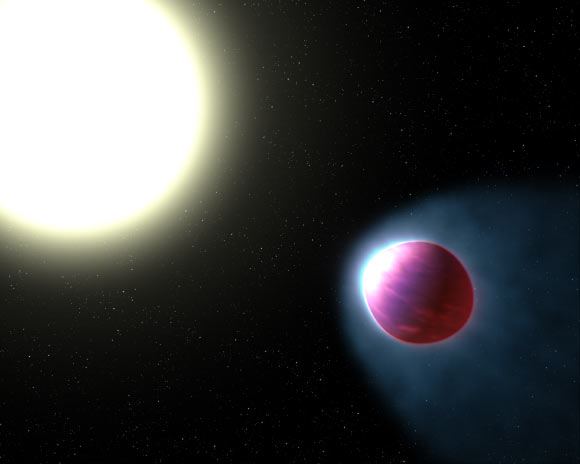

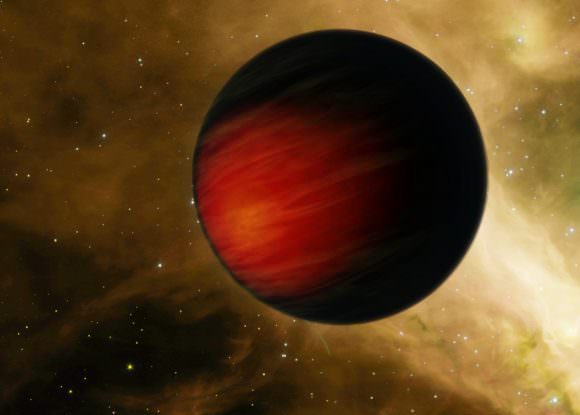

An unfortunate limitation to the technology is the fact that it won’t be able to resolve Earth-like planets. Especially where M-type (red dwarf) stars are concerned, these planets are likely to orbit too close to their parent stars to be observed clearly. However, it will be able to resolve Jupiter-sized gas giants and help characterize exozodiacal dust concentrations around nearby stars – both of which are priorities for NASA.

In the meantime, D’Amico and his colleagues will be using the Testbed for Rendezvous and Optical Navigation (TRON) to test their mDOT concept. This facility was specially-built by D’Amico to replicate the types of complex and unique illumination conditions that are encountered by sensors in space. In the coming years, he and his team will be working to ensure that the system works before creating an eventual prototype.

As D’Amico said of the work he and his colleagues at the SNL perform:

“I’m enthusiastic about my research program at Stanford because we’re tackling important challenges. I want to help answer fundamental questions and if you look in all current direction of space science and exploration – whether we’re trying to observe exoplanets, learn about the evolution of the universe, assemble structures in space or understand our planet – satellite formation-flying is the key enabler.”

Other projects that D’Amico and the SNL are currently engaged in include developing larger formations of tiny spacecraft (aka. “swarm satellites”). In the past, D’Amico has also collaborated with NASA on such projects as GRACE – a mission that mapped variations in Earth’s gravity field as part of the NASA Earth System Science Pathfinder (ESSP) program – and TanDEM-X, an SEA-sponsored mission which yielded 3D maps of Earth.

These and other projects which seek to leverage miniaturization for the sake of space exploration promise a new era of lower costs and greater accessibility. With applications ranging from swarms of tiny research and communications satellites to nanocraft capable of making the journey to Alpha Centauri at relativistic speeds (Breakthrough Starshot), the future of space looks pretty promising!

Be sure to check out this video of the TRON facility too, courtesy of Standford University:

Further Reading: Standford University