Welcome back to Constellation Friday! Today, in honor of the late and great Tammy Plotner, we will be dealing with the “Southern Crown” – the Corona Australis constellation!

In the 2nd century CE, Greek-Egyptian astronomer Claudius Ptolemaeus (aka. Ptolemy) compiled a list of all the then-known 48 constellations. This treatise, known as the Almagest, would be used by medieval European and Islamic scholars for over a thousand years to come, effectively becoming astrological and astronomical canon until the early Modern Age.

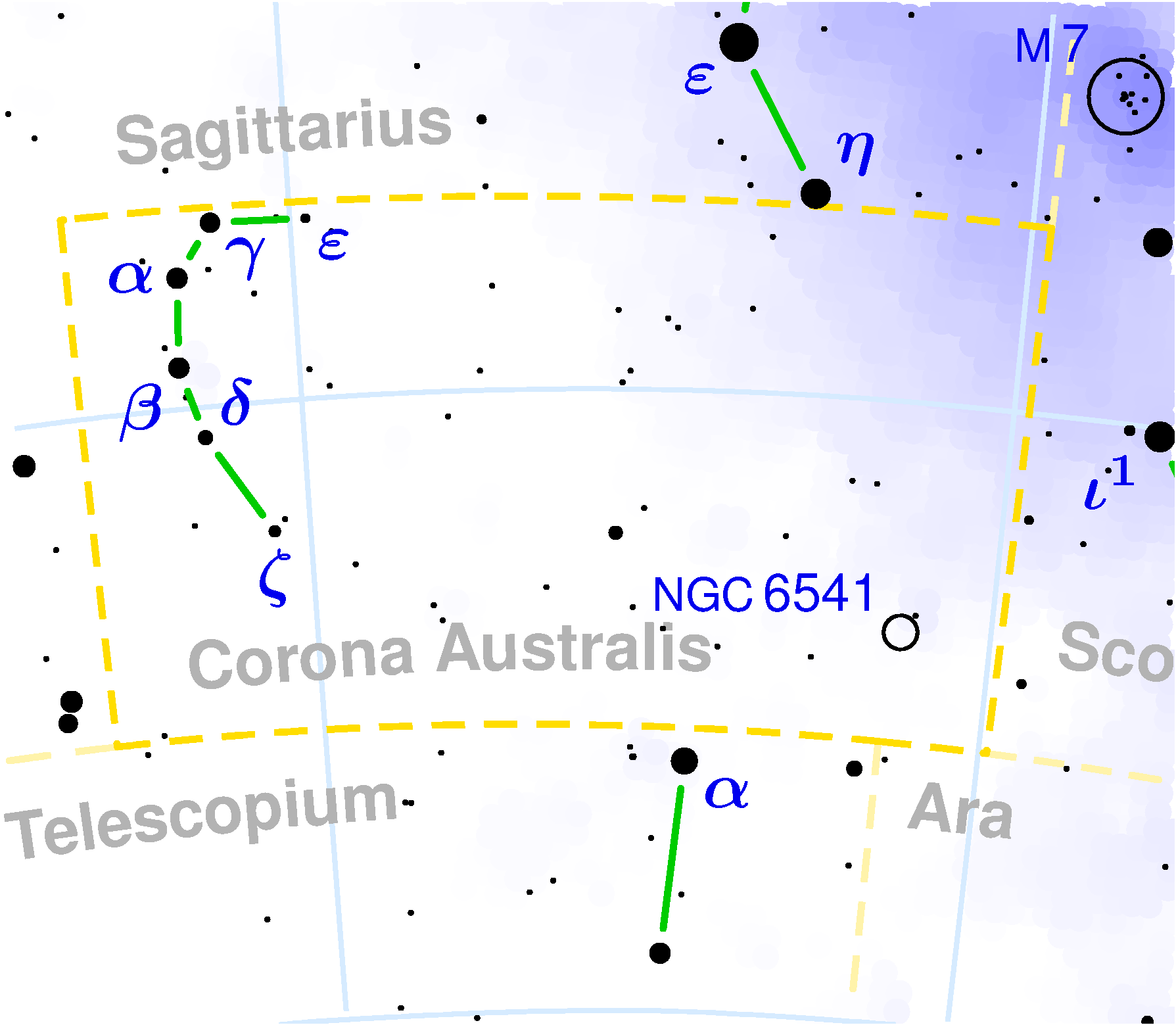

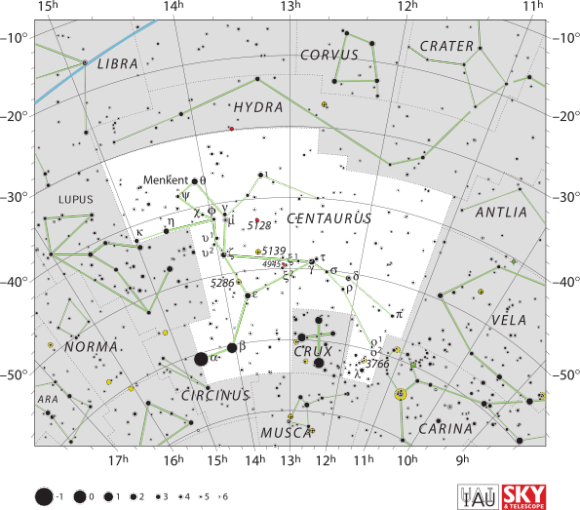

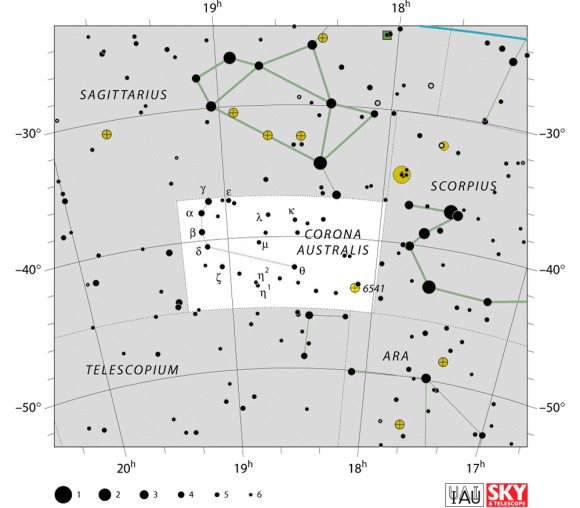

One of these was the Coronoa Australis constellation, otherwise known as the “Southern Crown”. This small, southern constellation is one of the faintest in the night sky, where it is bordered by the constellations of Sagittarius, Scorpius, Ara and Telescopium. Today, it is one of the 88 modern constellations recognized by the International Astronomical Union.

Name and Meaning:

Corona Australis – the “Southern Crown” – is the counterpart to Corona Borealis – the “Northern Crown”. To the ancient Greeks, this constellation wasn’t seen as a crown, but a laurel wreath. According to some myths, Dionysus was supposed to have placed a wreath of myrtle as a gift to his dead mother into the underworld as well. Either way, this small circlet of dim stars definitely has the appearance of a wreath – or crown – and belongs to legend!

History of Observation:

Like many of the Greek constellations, it is believed that Corona Australis was recorded by the ancient Mesopotamian in the MUL.APIN – where it may have been called MA.GUR (“The Bark”). While recorded by the Greeks as early as the 3rd century BCE, it was not until Ptolemy’s time (2nd century CE) that it was recorded as the “Southern Wreath”, a name that has stuck ever since.

In Chinese astronomy, the stars of Corona Australis are located within the Black Tortoise of the North and were known as ti’en pieh (“Heavenly Turtle”). During the Western Zhou period, the constellation marked the beginning of winter. To medieval Islamic astronomers, Corona Australis was known alternately as Al Kubbah (“the Tortoise”), Al Hiba (“the Tent”) or Al Udha al Na’am (“the Ostrich Nest”).

In 1920, the constellation was included in the list of 88 constellations formally recognized by the IAU.

Notable Objects:

Corona Australis is a small, faint constellation that has no bright stars, consists of 6 primary stars and contains 14 stellar members with Bayer/Flamsteed designations. There is one meteor shower associated with Corona Australis – the Corona-Australids which peak on or about March 16 each year and are active between March 14th through the 18th. The fall rate is minimal, with an average of about 5 to 7 per hour.

It’s brightest star, Alpha Coronae Australis (Alphekka Meridiana), is a class A2V star located about 130 light years from Earth. It is also the only properly-named star in the constellation. It’s second brightest star, Beta Coronae Australis, is a K-type bright giant located approximately 510 light years distant.

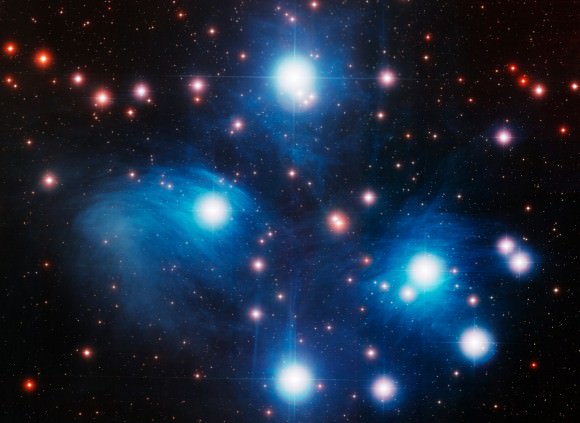

And then there’s R Coronae Australis, a well-known variable star that is located approximately 26.8 light years from Earth. This relatively young star is still in the process of formation – accreting material onto its surface from a circumstellar disk – and is located within a star forming region of dust and gas known as NGC 6726/27/29.

Corona Australis is also home to several Deep Sky Objects, such as the Corona Australis Nebula. This bright reflection nebula, which is located about 420 light years away, was formed when several bright stars became entangled with a dark cloud of dust. The cloud is a star-forming region, with clusters of young stars embedded inside, and consists of three nebulous regions – NGC 6726, NGC 6727, and NGC 6729.

Other reflection nebulas include NGC 6726/6727 and the fan-shaped NGC 6729. Corona Australis also boasts many star clusters, such as the large, bright globular cluster known as NGC 6541. There’s also the Coronet cluster, a small open star cluster that is located approximately 420 light years from Earth. The cluster lies at the heart of the constellation and is one of the nearest known regions that experiences ongoing star formation.

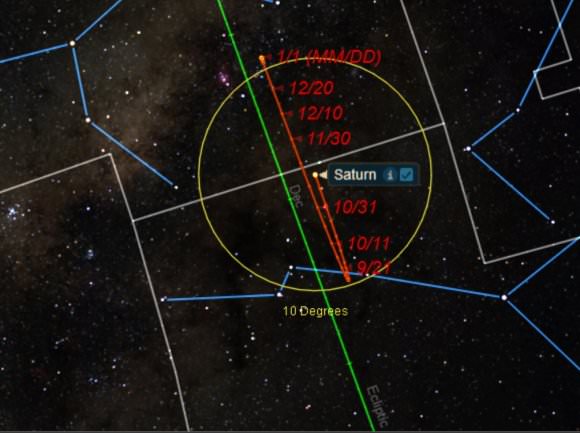

Finding Corona Australis:

Corona Australis is visible at latitudes between +40° and -90° and is best seen at culmination during the month of August. It can be explored using both binoculars and small telescopes. Let’s start with binoculars and a look at Alpha Coronae Australis – the only star in the constellation to have a proper name.

Called Alfecca Meridiana – or “the sixth star in the river Turtle” – Alpha is a spectral class A2V star which is located about 160 light years from Earth. Alfecca Meridiana is a fast rotator, spinning at least at 180 kilometers per second at its equator, 90 times faster than our Sun and making a full rotation in about 18 hours.

Even more interesting is the fact that Alpha is a Vega-like star, pouring out excess infrared radiation that appears to be coming from a surrounding disk of cool dust. Just what does that mean? It means that Alfecca Meridiana could possibly have a planetary system!

Now have a look at Beta. Although this orange class K (K0) giant star is rather ordinary, where it’s at is not. It’s sitting on the edge of the Corona Australis Molecular Cloud, a dusty, dark star-forming region which contains huge amounts of nebulae. While Beta does seem pretty plain, it is almost 5 times larger than our Sun and 730 times brighter. Not bad for a star that’s about a hundred million years old!

Now, take a look at a really bizarre star – Epsilon Coronae Australis. At a distance of 98 light years, there doesn’t seem to be much going on with this fifth magnitude, faint stellar point, but there is. That’s because Epsilon isn’t one star – but two. Epsilon is an eclipsing binary with two very similar eclipses that take place within an orbital period of 0.5914264 days, as first a faint star passes in front of the bright one that gives us 95 or so percent of the light, and then the bright one passes in front of the fainter.

So what does that mean? It means that if you sit right there at watch, you can see the changes in less than 7 hours. While watching for hours for a half magnitude drop might not seem like your cup of tea, think about what you’re watching…. These two stars are actually contacting each other as they go by! Can you imagine stars spinning so fast that they produce huge amounts of magnetic activity and dark starspots that also add to the variation as they swing in and out of view? Sharing mass and pulling at each other in just a matter of hours? Now that’s a show worth watching…

Now try variable star R Coronae Borealis (RA 19 53 65 Dec -36 57 97). Here we have another unusual one – a “Herbig Ae/Be” pre-main sequence star. The star is an irregular variable with more frequent outbursts during times of greater average brightness, but it also has a long-term periodic variation of about 1,500 days and about 1/2 magnitude that may be linked to changes in its circumstellar shell, rather than to stellar pulsations. Although R Coronae Australis is 40 times brighter than Sol, and about 2 to 10 times larger, most of its stellar luminosity is obscured because the star is still accreting matter. Protoplanetary bodies? Maybe!

Keep your binoculars handy and get out the telescope as we start deep sky first with NGC 6541. Also known as Caldwell 78 and Bennett 104, this beautiful 6th magnitude globular cluster was first discovered by N. Cacciatore on March 19, 1826. It belongs in our Milky Way galaxy’s inner halo structure and it is rather metal poor in structure – but beautifully resolved in a telescope. In binoculars, this splendid southern sky study will appear as a large faint globular with a bright star to the northeast.

Now head for the telescope and NGC 6496 (RA 17 59 0 Dec -44 16). At right around magnitude 9, this globular cluster also has a bonus nebula attached to it. Collectively known as Bennett 100, Dreyer described it as a “nebula plus cluster” but it will take dark skies to make out both. Look for 5th magnitude star SAO 228562 that accompanies it. In a small telescope, only a hazy, faint patch can be seen, but larger aperture does get some resolution.

Try emission/reflection nebula NGC 6729 (RA 19 01 55 Dec -36 57 30) next. In a wide field, you can place NGC 6726, NGC 6727, NGC 6729 and the double star BSO 14 in the same eyepiece. The three nebulae NGC 6726-27, and NGC 6729 were discovered by Johann Friedrich Julius Schmidt, during his observations at Athen Observatory in 1861. The nebula are very faint and almost comet-like in appearance and the double star is easily split. Don’t forget to mark your notes as having captured Caldwell 68!

We have written many interesting articles about the constellation here at Universe Today. Here is What Are The Constellations?, What Is The Zodiac?, and Zodiac Signs And Their Dates.

Be sure to check out The Messier Catalog while you’re at it!

For more information, check out the IAUs list of Constellations, and the Students for the Exploration and Development of Space page on Canes Venatici and Constellation Families.

Sources: