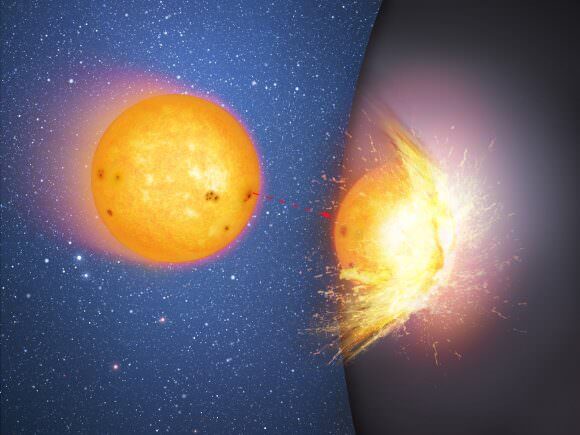

When a large star undergoes gravitational collapse near the end of its lifespan, a neutron star is often the result. This is what remains after the outer layers of the star have been blown off in a massive explosion (i.e. a supernova) and the core has compressed to extreme density. Afterwards, the star’s rotation rate increases considerably, and where they emit beams of electromagnetic radiation, they become “pulsars”.

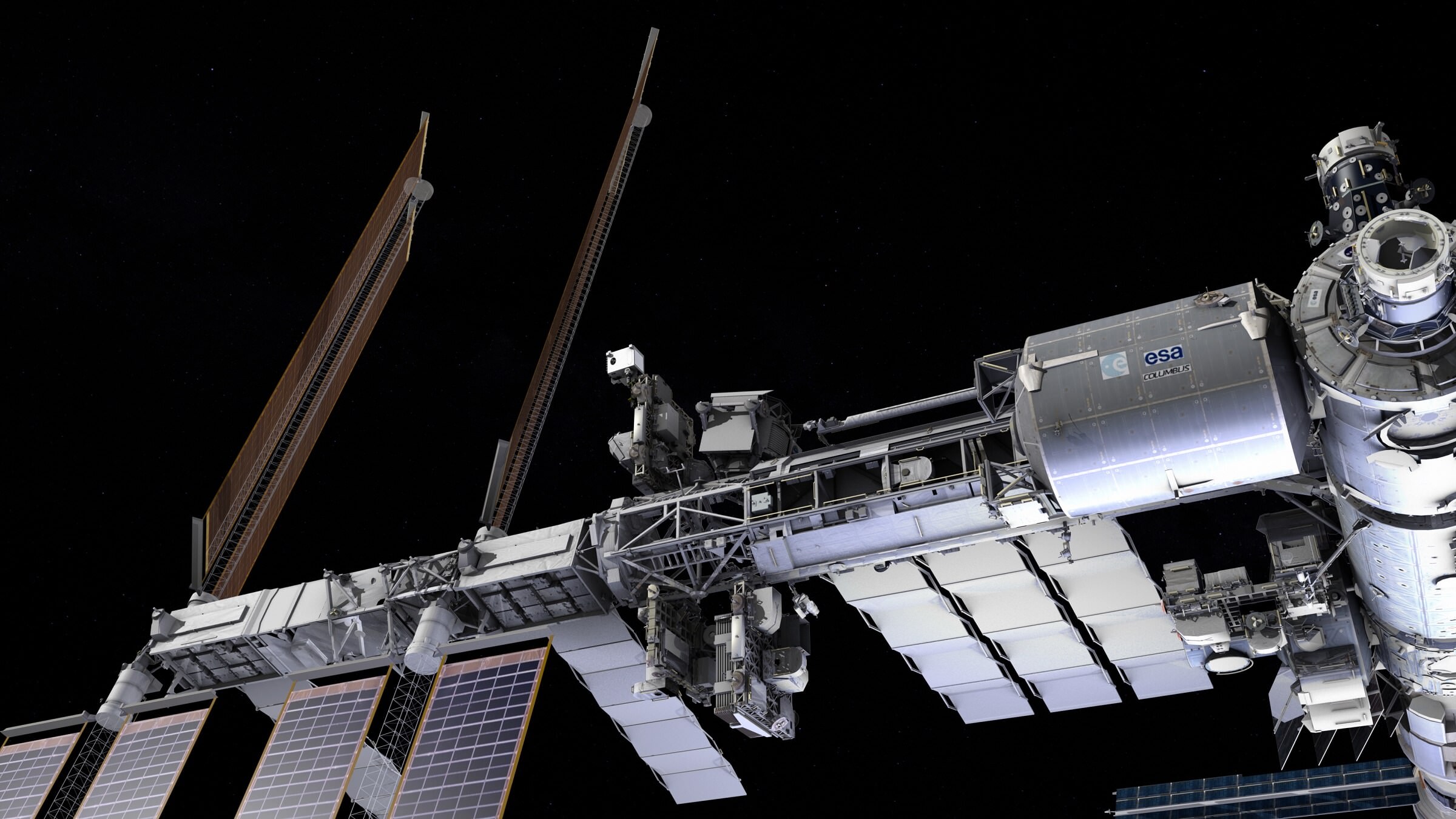

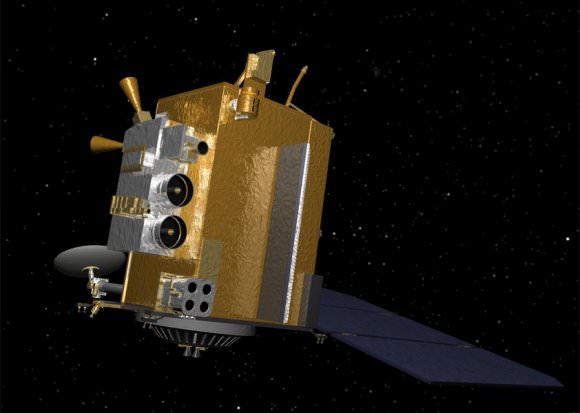

And now, 50 years after they were first discovered by British astrophysicist Jocelyn Bell, the first mission devoted to the study of these objects is about to be mounted. It is known as the Neutron Star Interior Composition Explorer (NICER), a two-part experiment that will be deployed to the International Space Station this summer. If all goes well, this platform will shed light on one of the greatest astronomical mysteries, and test out new technologies.

Astronomers have been studying neutron stars for almost a century, which have yielded some very precise measurements of their masses and radii. However, what actually transpires in the interior of a neutron star remains an enduring mystery. While numerous models have been advanced that describe the physics governing their interiors, it is still unclear how matter would behave under these types of conditions.

Not surprising, since neutron stars typically hold about 1.4 times the mass of our Sun (or 460,000 times the mass of the Earth) within a volume of space that is the size of a city. This kind of situation, where a considerable amount of matter is packed into a very small volume – resulting in crushing gravity and an incredible matter density – is not seen anywhere else in the Universe.

As Keith Gendreau, a scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, explained in a recent NASA press statement:

“The nature of matter under these conditions is a decades-old unsolved problem. Theory has advanced a host of models to describe the physics governing the interiors of neutron stars. With NICER, we can finally test these theories with precise observations.”

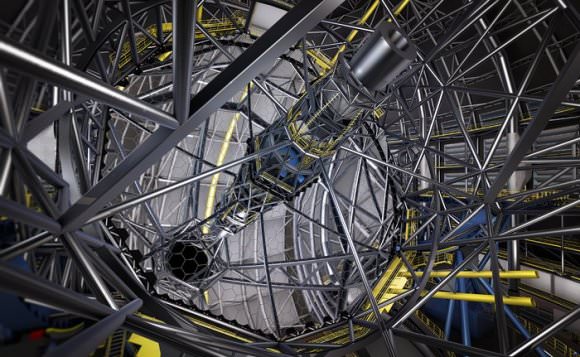

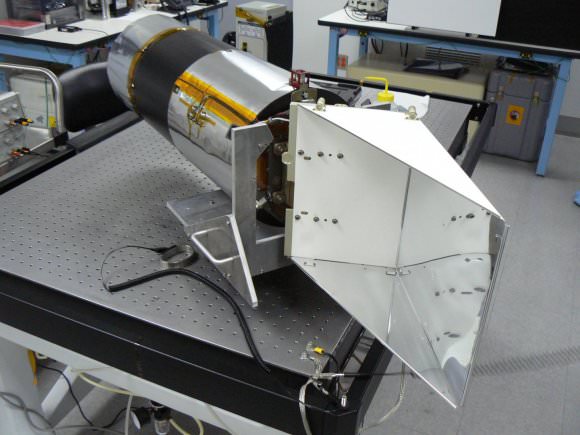

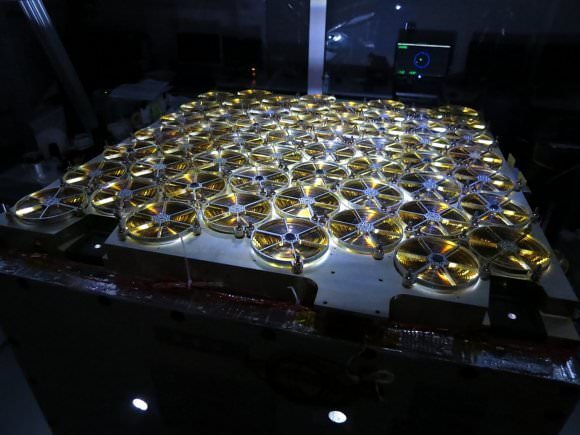

NICE was developed by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center with the assistance of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), the Naval Research Laboratory, and universities across the U.S. and Canada. It consists of a refrigerator-sized apparatus that contains 56 X-ray telescopes and silicon detectors. Though it was originally intended to be deployed late in 2016, a launch window did not become available until this year.

Once installed as an external payload aboard the ISS, it will gather data on neutron stars (mainly pulsars) over an 18-month period by observing neutron stars in the X-ray band. Even though these stars emit radiation across the spectrum, X-ray observations are believed to be the most promising when it comes to revealing things about their structure and various high-energy phenomena associated with them.

These include starquakes, thermonuclear explosions, and the most powerful magnetic fields known in the Universe. To do this, NICER will collect X-rays generated from these stars’ magnetic fields and magnetic poles. This is key, since it is at the poles that the strength of a neutron star’s magnetic fields causes particles to be trapped and rain down on the surface, which produces X-rays.

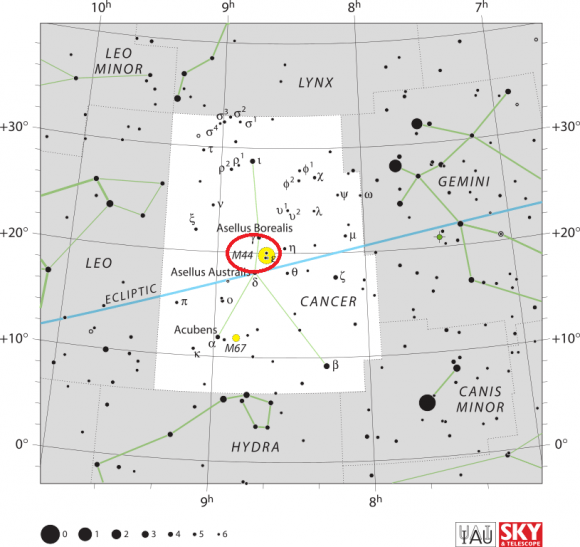

In pulsars, it is these intense magnetic fields which cause energetic particles to become focused beams of radiation. These beams are what give pulsars their name, as they appear like flashes thanks to the star’s rotation (giving them their “lighthouse”-like appearance). As physicists have observed, these pulsations are predictable, and can therefore be used the same way atomic-clocks and Global Positioning System are here on Earth.

While the primary goal of NICER is science, it also offers the possibility of testing new forms of technology. For instance, the instrument will be used to conduct the first-ever demonstration of autonomous X-ray pulsar-based navigation. As part of the Station Explorer for X-ray Timing and Navigation Technology (SEXTANT), the team will use NICER’s telescopes to detect the X-ray beams generated by pulsars to estimate the arrival times of their pulses.

The team will then use specifically-designed algorithms to create an on-board navigation solution. In the future, interstellar spaceships could theoretically rely on this to calculate their location autonomously. This wold allow them to find their way in space without having to rely on NASA’s Deep Space Network (DSN), which is considered to be the most sensitive telecommunications system in the world.

Beyond navigation, the NICER project also hopes to conduct the first-ever test of the viability of X-ray based-communications (XCOM). By using X-rays to send and receive data (in the same way we currently use radio waves), spacecraft could transmit data at the rate of gigabits per second over interplanetary distances. Such a capacity could revolutionize the way we communicate with crewed missions, rover and orbiters.

Central to both demonstrations is the Modulated X-ray Source (MXS), which the NICER team developed to calibrate the payload’s detectors and test the navigation algorithms. Generating X-rays with rapidly varying intensity (by switching on and off many times per second), this device will simulate a neutron star’s pulsations. As Gendreau explained:

“This is a very interesting experiment that we’re doing on the space station. We’ve had a lot of great support from the science and space technology folks at NASA Headquarters. They have helped us advance the technologies that make NICER possible as well as those that NICER will demonstrate. The mission is blazing trails on several different levels.”

It is hoped that the MXS will be ready to ship to the station sometime next year; at which time, navigation and communication demonstrations could begin. And it is expected that before July 25th, which will mark the 50th anniversary of Bell’s discovery, the team will have collected enough data to present findings at scientific conferences scheduled for later this year.

If successful, NICER could revolutionize our understanding of how neutron stars (and how matter behaves in a super-dense state) behaves. This knowledge could also help us to understand other cosmological mysteries such as black holes. On top of that, X-ray communications and navigation could revolutionize space exploration and travel as we know it. In addition to providing greater returns from robotic missions located closer to home, it could also enable more lucrative missions to locations in the outer Solar System and even beyond.

Further Reading: NASA