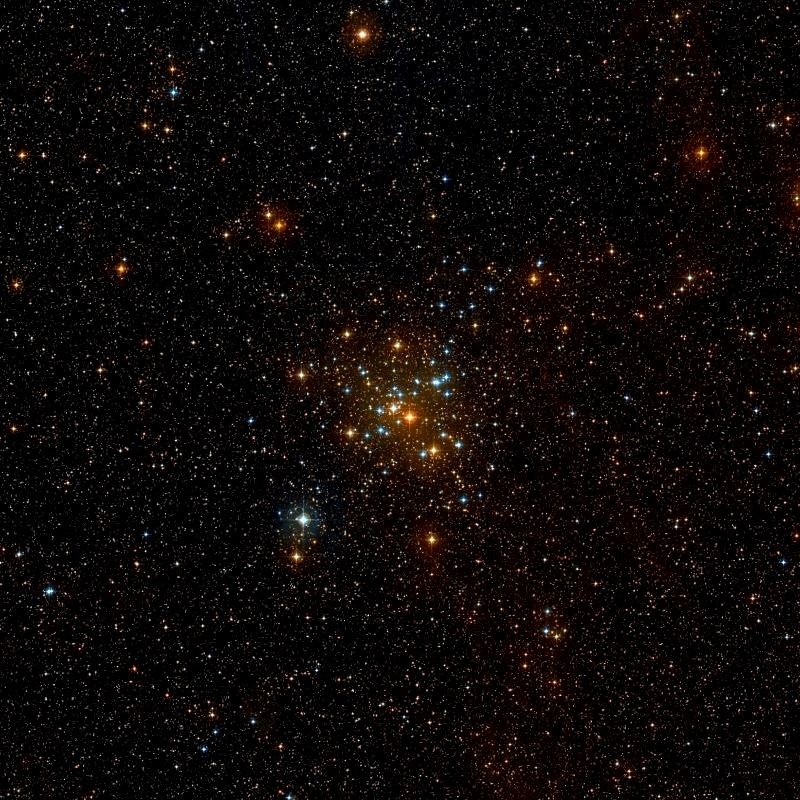

Welcome back to Messier Monday! In our ongoing tribute to the great Tammy Plotner, we take a look at the double star known as Messier 41. Enjoy!

During the 18th century, famed French astronomer Charles Messier noted the presence of several “nebulous objects” in the night sky. Having originally mistaken them for comets, he began compiling a list of them so that others would not make the same mistake he did. In time, this list (known as the Messier Catalog) would come to include 100 of the most fabulous objects in the night sky.

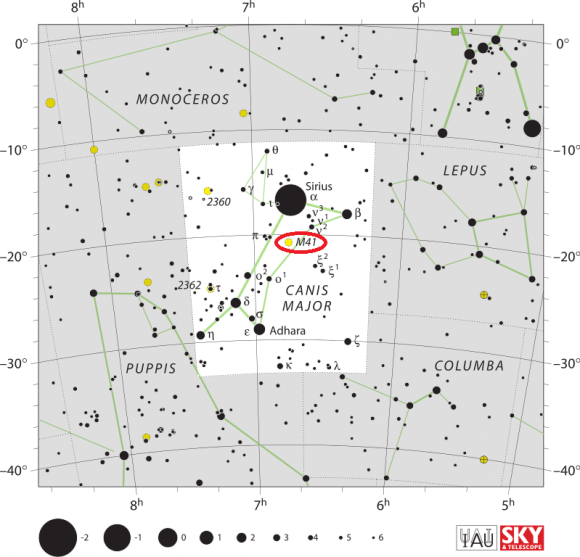

One of these objects is the open star cluster known as Messier 41 (aka. M41, NGC 2287). Located in the Canis Major constellation – approximately 4,300 light years from Earth – this cluster lies just four degrees south of Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky. Like most open clusters, it is relatively young – 190 million years old – and contains over 100 stars in a region measuring 25 to 26 light years in diameter.

Description:

Running away from us at a speed of about 34 kilometers per second, this field of about 100 stars measures about 25 light years across. Born about 240 million years ago, it resides in space approximately 2300 light years away from our solar system. Larger aperture telescopes will reveal the presence of many red (or orange) giant stars and the hottest star in this group is a spectral type A.

As G.L.H. Harris (et al) explained in a 1993 study:

“We have obtained photoelectric UBV photometry for 100 stars, uvbyb photometry for 39 stars and MK spectral types for 80 stars in the field of NGC 2287. After combination with data from other sources, several interesting cluster properties are apparent. Both the UBV and uvbyb photometry point to a small but nonzero reddening, while our spectral types confirm previous results indicating a high binary frequency for the cluster. Based on our spectral and photometric data for the cluster members, we find a minimum binary frequency of 40% and discuss the possibility that the results may imply a binary frequency closer to 80%. The cluster age is found to be based on both the main-sequence turnoff and the red giant distribution; the width of the turn up region can probably be explained by a combination of duplicity and a range in stellar rotation.”

But there’s more than just red giant stars and various spectral types to be found hiding in Messier 41. There’s at least two white dwarf stars, too. As P.D Dobbie explained in a 2009 study:

“[W]e use our estimates of their cooling times together with the cluster ages to constrain the lifetimes and masses of their progenitor stars. We examine the location of these objects in initial mass-final mass space and find that they now provide no evidence for substantial scatter in initial mass-final mass relation (IFMR) as suggested by previous investigations. This form is generally consistent with the predictions of stellar evolutionary models and can aid population synthesis models in reproducing the relatively sharp drop observed at the high mass end of the main peak in the mass distribution of white dwarfs.”

As you view Messier 41, you’ll be impressed with its wide open appearance… and knowing it’s simply what happens to star clusters as they get passed around our galaxy. As Giles Bergond (et al.) stated in their 2001 study:

“Taking into account observational biases, namely the galaxy clustering and differential extinction in the Galaxy, we have associated these stellar overdensities with real open cluster structures stretched by the galactic gravitational field. As predicted by theory and simulations, and despite observational limitations, we detected a general elongated (prolate) shape in a direction parallel to the galactic Plane, combined with tidal tails extended perpendicularly to it. This geometry is due both to the static galactic tidal field and the heating up of the stellar system when crossing the Disk. The time varying tidal field will deeply affect the cluster dynamical evolution, and we emphasize the importance of adiabatic heating during the Disk-shocking. During the 10-20 Z-oscillations experienced by a cluster before its dissolution in the Galaxy, crossings through the galactic Disk contribute to at least 15% of the total mass loss. Using recent age estimations published for open clusters, we find a destruction time-scale of about 600 million years for clusters in the solar neighborhood.”

That means we’ve only got another 360 million years to observe it before it’s completely gone (though some estimates place it at about 500 million). Either way, this star cluster is destined to disappear, perhaps before we are!

History of Observation:

Messier 41 was “possibly” recorded by Aristotle about 325 B.C. as a patch in the Milky Way… quite understandable since it is very much within unaided eye visibility from a dark sky location. Said Aristotle:

“.. some of the fixed stars have tails. And for this we need not rely only on the evidence of the Egyptians who say they have observed it; we have observed it also ourselves. For one of the stars in the thigh of the Dog had a tail, though a dim one: if you looked hard at it the light used to become dim, but to less intent glance it was brighter.”

However, Giovanni Batista Hodierna was the first to catalog it in 1654, and the star cluster became a bit more astronomically known when John Flamsteed independently found it again on February 16, 1702. Doing his duty, Charles Messier also logged it:

“In the night of January 16 to 17, 1765, I have observed below Sirius and near the star Rho of Canis Major a star cluster; when examining it with a night refractor, this cluster appeared nebulous; instead, there is nothing but a cluster of small stars. I have compared the middle with the nearest known star; and I found its right ascension of 98d 58′ 12″, and its declination 20d 33′ 50″ north.”

Following suit, other historical astronomers also observed M41 – including Sir John Herschel to include it in the NGC catalog. While none found it particularly thrilling… their notes range from a “coarse collection of stars” to “very large, bright, little compressed”, perhaps you will feel much differently about this easy, bright target!

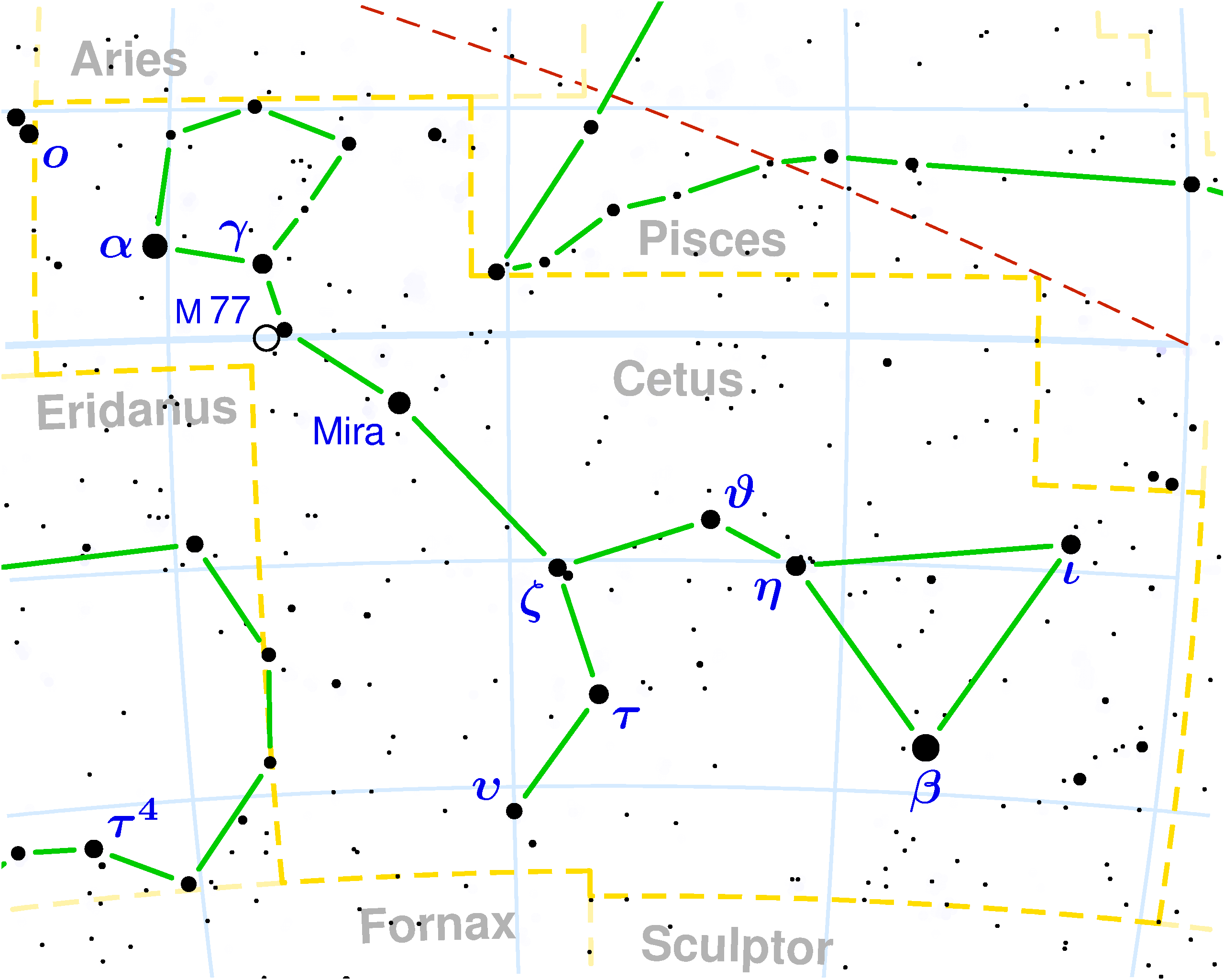

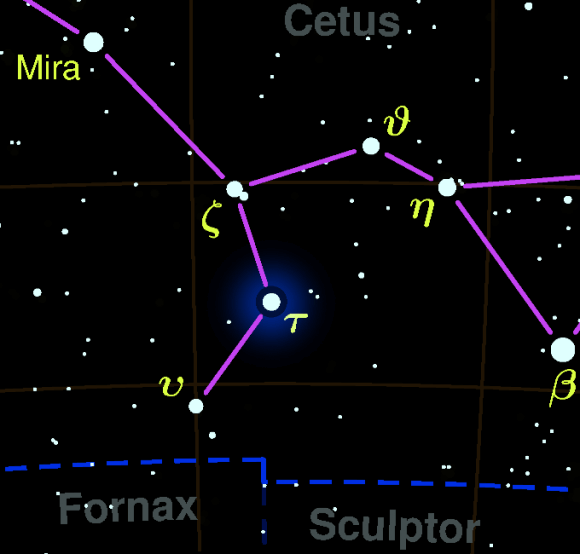

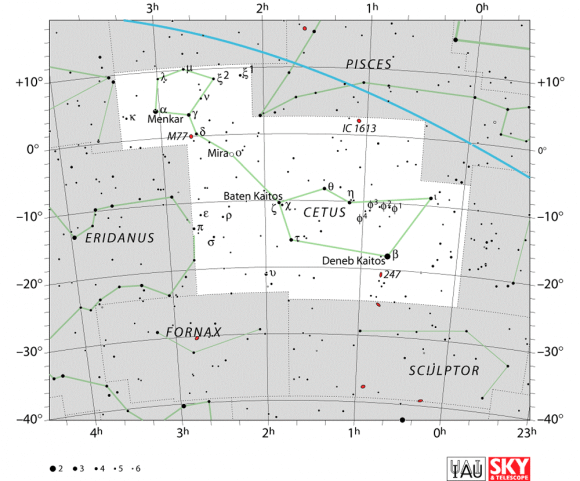

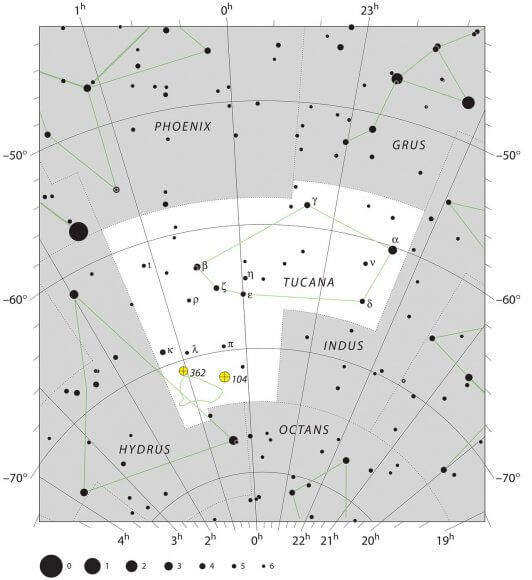

Locating Messier 41:

Finding Messier 41 isn’t very difficult for binoculars and small telescopes – all you have to know is the brightest star in the northern hemisphere, Sirius, and south! Simply aim your optics at Sirius and move due south approximately four degrees. That’s about one standard field of view for binoculars, about one field of view for the average telescope finderscope and about 6 fields of view for the average wide field, low power eyepiece.

Because Messier 41 is a large star cluster, remember to use lowest magnification to get the best effect. Higher magnification can always be used once the star cluster is identified to study individual members. M41 is quite bright and easily resolved and makes a wonderful target for urban skies and moonlit nights!

Because you understand what’s there…

Object Name: Messier 41

Alternative Designations: M41, NGC 2287

Object Type: Open Galactic Star Cluster

Constellation: Canis Major

Right Ascension: 06 : 46.0 (h:m)

Declination: -20 : 44 (deg:m)

Distance: 2.3 (kly)

Visual Brightness: 4.5 (mag)

Apparent Dimension: 38.0 (arc min)

We have written many interesting articles about Messier Objects here at Universe Today. Here’s Tammy Plotner’s Introduction to the Messier Objects, , M1 – The Crab Nebula, M8 – The Lagoon Nebula, and David Dickison’s articles on the 2013 and 2014 Messier Marathons.

Be to sure to check out our complete Messier Catalog. And for more information, check out the SEDS Messier Database.

Sources: