Been missing the evening planets? Currently, Saturn and Venus rule the dawn, and Mars is sinking into the dusk as it recedes towards the far side of the Sun. The situation has been changing for one planet however, as Jupiter reaches opposition this week.

Jupiter in 2017

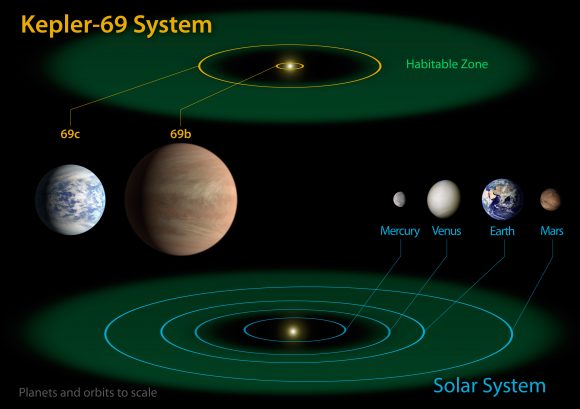

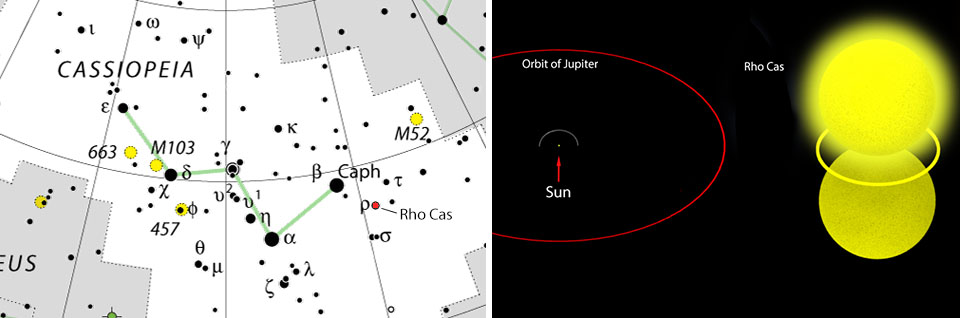

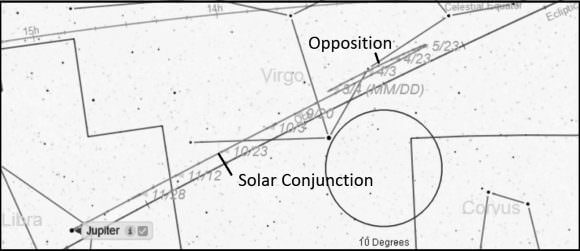

Currently in the constellation Virgo near the September equinoctial point where the celestial equator meets the ecliptic in 2017, Jupiter rules the evening skies. Orbiting the Sun once every 11.9 years, Jupiter moves roughly one zodiacal constellation eastward per year, as oppositions for Jupiter occur about once every 399 days.

As the name implies, “opposition” is simply the point at which a planet seems to rise “opposite” to the setting Sun.

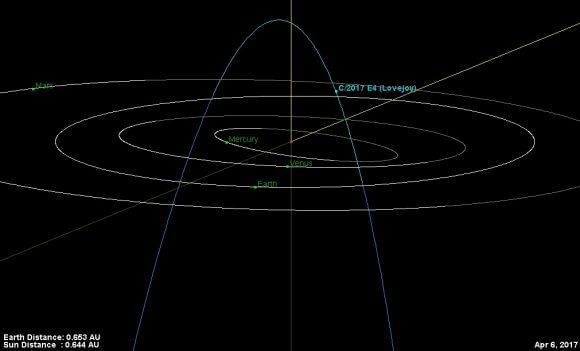

At opposition 2017 on Friday, April 7th, Jupiter shines at magnitude -2.5 and is 666.5 million kilometers distant. Jupiter just passed aphelion on February 16th, 2017 at 5.46 AU 846 million kilometers from the Sun, making this and recent oppositions slightly less favorable. An April opposition for Jupiter also means it’ll now start to occur in the southern hemisphere for this and the next several years. Jupiter crosses the celestial equator northward again in 2022.

Can you see Ganymede with the naked eye? Shining at magnitude +4.6, the moon lies just on the edge of naked eye visibility from a dark sky site… the problem is, the moon never strays more than 5′ from the dazzling limb of Jupiter. Here’s a fun and easy experiment: attempt to spot Ganymede through this month’s opposition season, using nothing more than a pair of MK-1 eyeballs. Then at the end of the month, check an ephemeris for greatest elongations of the moon. Any matches?

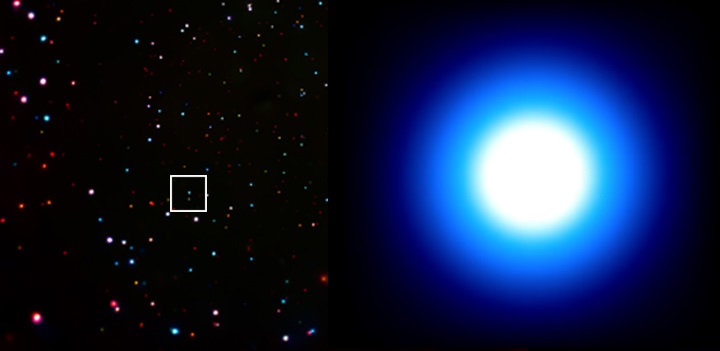

With binoculars, the first thing you’ll notice is the four bright Galilean moons of Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto. At about 10x magnification or so, Jupiter will begin to resolve as a disk. With binoculars, you get a very similar view of Jupiter as Galileo had with his primitive spy glass.

At the telescope eyepiece at low power you can see the main cloud bands of Jove, the northern and southern equatorial belts. Shadow transits and eclipses of the Jovian moons are also fun to watch, and frequent for the innermost two moons Io and Europa. Orbiting Jupiter once every seven days, transits of Ganymede are less frequent, and outermost Callisto is the only moon that can “miss” Jupiter on occasion, as it does this year until transits resume in 2020.

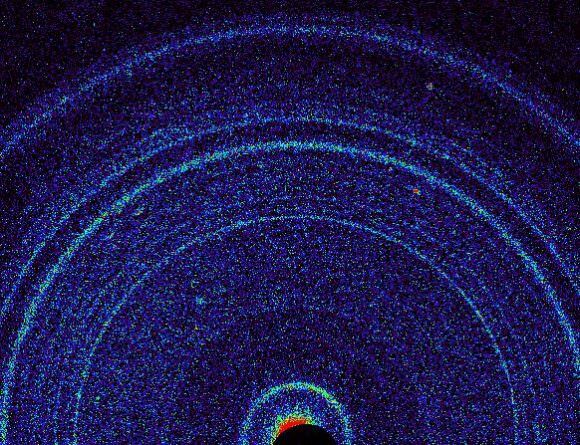

Jupiter’s one of the best planets for imaging: unlike Venus or bashful Mars, things are actually happening on the cloudtops of Jove. You can see smaller storms come and go as the Great Red Spot make its circuit once every 10 hours. Follow Jupiter from sunset through sunrise, and it will rotate just about all the way around once. Strange to think, we’ve been using modified webcams to image Jupiter for over a decade and a half now.

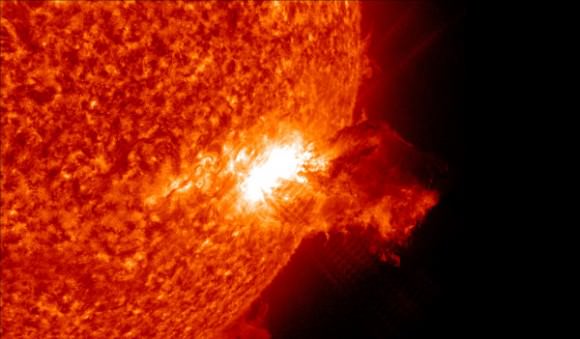

The major moons of Jupiter cast shadows nearly straight back as seen from our vantage point near opposition. After opposition, the shadows of the moons and the planet itself begin to slide to one side and will continue to do so as the planet heads towards quadrature 90 degrees east of the Sun. In 2017, quadrature for Jupiter occurs on July 5th as the planet sits due south for northern hemisphere observers at sunset. Distances to Jupiter vary through opposition, quadrature and solar conjunction, and Danish astronomer Ole Rømer used discrepancies in predictions versus actual observed phenomena of Jupiter’s moons to make the first good estimation of the speed of light in 1676.

Double shadow transits are also interesting to watch, and a season of double events involving Io and Europa begins next month on May 12th.

Jupiter will rule the dusk skies until solar conjunction on October 26th, 2017.

It’s also interesting to note that while the Northern Equatorial Belt has been permanent over the last few centuries of telescopic observation, the Southern Equatorial Belt seems to pull a disappearing act roughly every decade or so. This last occurred in 2010, and we might just be due again over the next few years. The Great Red Spot has also looked a little more pale and salmon over the last few years, and may vanish altogether this century.

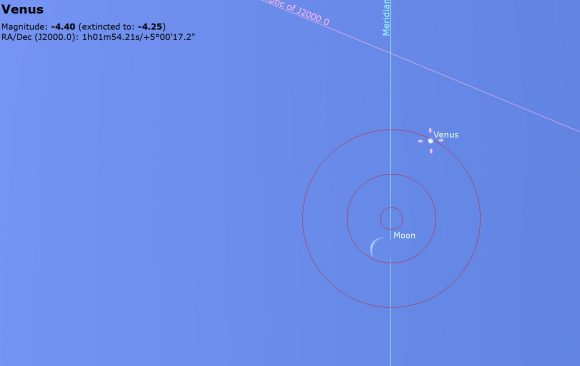

Finally, the Full Moon typically sits near a given planet near opposition, as occurs next week on the evening of April 10/11th.

The next occultation of Jupiter by the Moon occurs on October 31st, 2019.

Don’t miss a chance to observe the king of the planets in 2017.

– Here’s a handy JoveMoons for Android and Iphone for planning your next Jovian observing session.

-Be sure to check out our complete guide to oppositions, elongations, occultations and more with our 101 Astronomical Events for 2017, a free e-book from Universe Today.

-Send those images of Jupiter in to Universe Today’s Flickr forum.