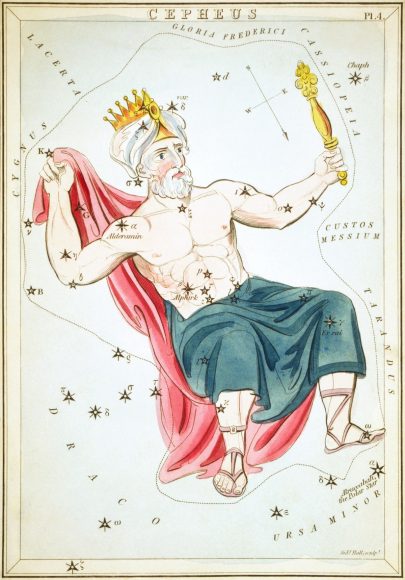

Welcome back to Constellation Friday! Today, in honor of the late and great Tammy Plotner, we will be dealing with the King of Ethiopia himself, the Cepheus constellation!

In the 2nd century CE, Greek-Egyptian astronomer Claudius Ptolemaeus (aka. Ptolemy) compiled a list of all the then-known 48 constellations. This treatise, known as the Almagest, would be used by medieval European and Islamic scholars for over a thousand years to come, effectively becoming astrological and astronomical canon until the early Modern Age.

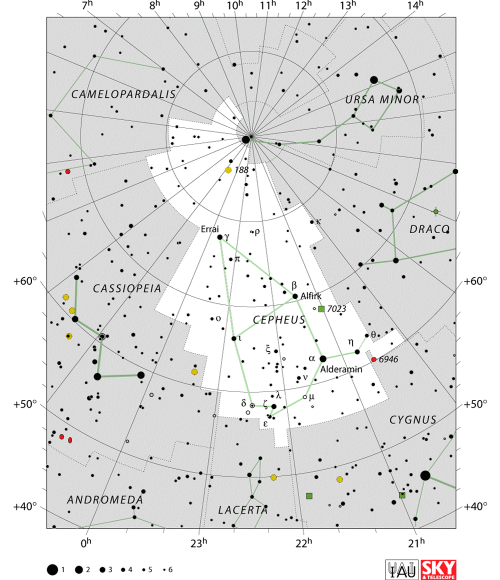

One of these is the northern constellation of Cepheus, named after the mythological king of Ethiopia. Today, it is one of the 88 modern constellations recognized by the IAU, and is bordered by the constellations of Camelopardalis, Cassiopeia, Cygnus, Draco, Lacerta, and Ursa Minor.

Name and Meaning:

In Greek mythology, Cepheus represents the mythical king of Aethiopia – and husband to the vain queen Cassiopeia. This also makes him the father of the lovely Andromeda, and a member of the entire sky saga which involves jealous gods and mortal boasts. According to this myth, Zeus placed Cepheus in the sky after his tragic death, which resulted from a jealous lovers’ spat.

It began when Cepheus’ wife – Cassiopeia – boasted that she was more beautiful than the Nereids (the sea nymphs), which angered the nymphs and Poseidon, god of the sea. Poseidon sent a sea monster, represented by the constellation Cetus, to ravage Cepheus’ land. To avoid catastrophe, Cepheus tried to sacrifice his daughter Andromeda to Cetus; but she was saved by the hero Perseus, who also slew the monster.

The two were to be married, but this created conflict since Andromeda had already been promised to Cepheus brother, Phineus. A fight ensued, and Perseus was forced to brandish the head of Medusa to defeat his enemies, which caused Cepheus and Cassiopeia (who did not look away in time) to turn to stone. Perhaps his part in the whole drama is why his crown only appears to be seen in the fainter stars when he’s upside down?

History of Observation:

As one of the 48 fabled constellations from Greek mythology, Cepheus was included by Ptolemy in his 2nd century tract, The Almagest. In 1922, it was included in the 88 modern constellations recognized by the International Astronomical Union (IAU).

Notable Features:

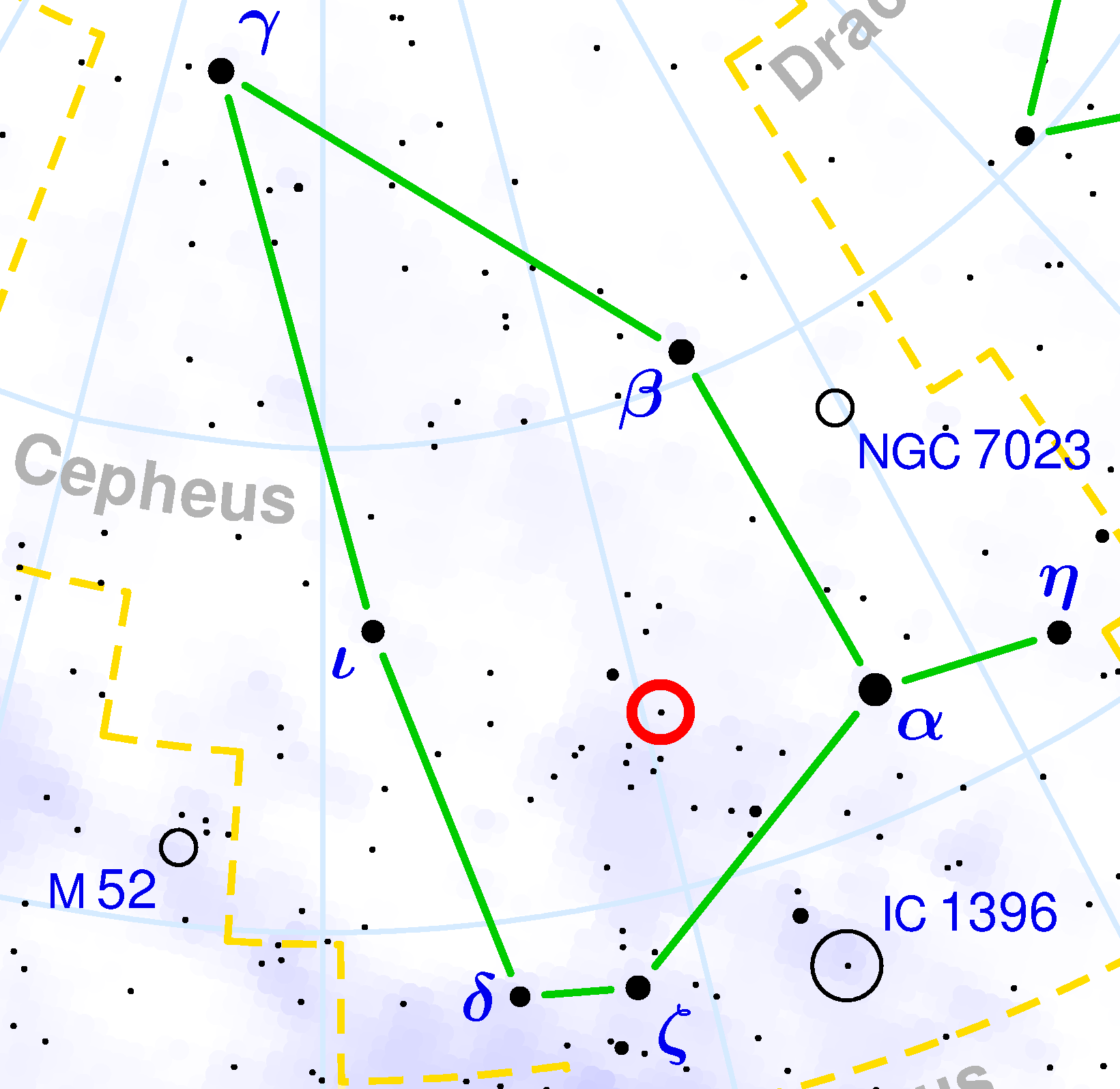

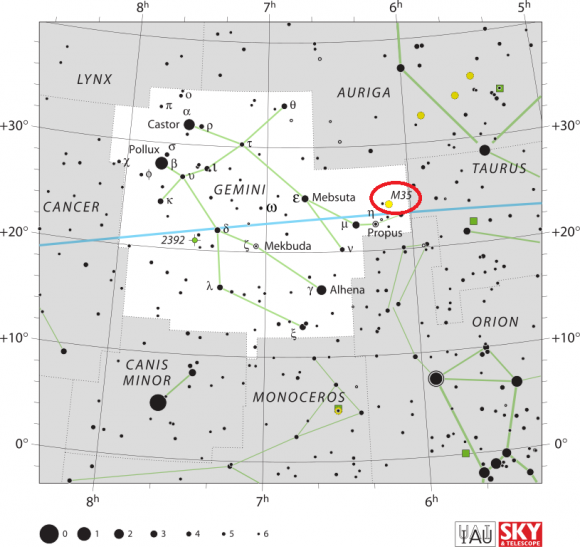

Bordered by Cygnus, Lacerta and Cassiopeia, it contains only one bright star, but seven major stars and 43 which have Bayer/Flamsteed designations. It’s brightest star, Alpha Cephei, is a white class A star, which is located about 48 light years away. Its traditional name (Alderamin) is derived from the Arabic “al-dira al-yamin“, which means “the right arm”.

Next is Beta Cephei, a triple star systems that is approximately 690 light years from Earth. The star’s traditional name, Alfirk, is derived from the Arabic “al-firqah” (“the flock”). The brightest component in this system, Alfirk A, is a blue giant star (B2IIIev), which indicates that it is a variable star. In fact, this star is a prototype for Beta Cephei variables – main sequence stars that show variations in brightness as a result of pulsations of their surfaces.

Then there’s Delta Cephei, which is located approximately 891 light years from the Solar System. This star also serves as a prototype for Cepheid variables, where pulsations on its surface are directly linked to changes in luminosity. The brighter component of the binary is classified as a yellow-white F-class supergiant, while its companion is believed to be a B-class star.

Gamma Cephei is another binary star in Cepheus, which is located approximately 45 light years away. The star’s traditional name is Alrai (Er Rai or Errai), which is derived from the Arabic ar-r?‘?, which means “the shepherd.” Gamma Cephei is an orange subgiant (K1III-IV) that can be seen by the naked eye, and its companion has about 0.409 solar masses and is thought to be an M4 class red dwarf.

Cepheus is also home to many notable Deep Sky Objects. For example, there’s NGC 6946, which is sometimes called the Fireworks Galaxy because of its supernovae rate and high volume of star formation. This intermediate spiral galaxy is located approximately 22 million light years distant. The galaxy was discovered by William Herschel in September 1798, and nine supernovae have been observed in it over the last century.

Next up is the Wizard Nebula (NGC 7380), an open star cluster that was discovered by Caroline Herschel in 1787. The cluster is embedded in a nebula that is about 110 light years in size and roughly 7,000 light years from our Solar System. It is also a relatively young open cluster, as its stars are estimated to be less than 500 million years old.

Then there’s the Iris Nebula (NGC 7023), a reflection nebula with an apparent magnitude of 6.8 that is approximately 1,300 light years distant. The object is so-named because it is actually a star cluster embedded inside a nebula. The nebula is lit by the star SAO 19158 and it lies close to two relatively bright stars – T Cephei, which is a Mira type variable, and Beta Cephei.

Discovered by Sir William Herschel on October 18, 1794, Herschel made the correct assumption of, “A star of 7th magnitude. Affected with nebulosity which more than fills the field. It seems to extend to at least a degree all around: (fainter) stars such as 9th or 10th magnitude, of which there are many, are perfectly free from this appearance.”

So where did the confusion come in? It happened in 1931 when Per Collinder decided to list the stars around it as a star cluster Collinder 429. Then along came Mr. van den Berg, and the little nebula became known as van den Berg 139. Then the whole group became known as Caldwell 4! So what’s right and what isn’t?

According to Brent Archinal, “I was surprised to find NGC 7023 listed in my catalog as a star cluster. I assumed immediately the Caldwell Catalog was in error, but further checking showed I was wrong! The Caldwell Catalog may be the only modern catalog to get the type correctly!”

Finding Cepheus:

Cepheus is a circumpolar constellation of the northern hemisphere and is easily seen at visible at latitudes between +90° and -10° and best seen during culmination during the month of November. For the unaided eye observer, start first with Cepheus’ brightest star – Alpha. It’s name is Alderamin and it’s going through stellar evolution – moving off the main sequence into a subgiant, and on its way to becoming a red giant as its hydrogen supply depletes.

What’s very cool is Alderamin is located near the precessional path traced across the celestial sphere by the Earth’s north pole. That means that periodically this star comes within 3° of being a pole star! Keeping that in mind, head off for Gamma Cephei. Guess what? Due to the precession of the equinoxes, Errai will become our northern pole star around 3000 AD and will make its closest approach around 4000 AD. (Don’t wait up, though… It will be late).

However, you can stay up late enough with a telescope or binoculars to have a closer look at Errai, because its an orange subgiant binary star that’s also about to go off the main sequence and its accompanied by a red dwarf star. What’s so special about that? Well, maybe because a planet has been discovered floating around there, too!

Now let’s have some fun with a Cepheid variable star that changes enough in about 5 days to make watching it fun! You’ll find Delta on the map as the figure 8 symbol and in the sky you’ll find it 891 light-years away. Delta Cephei is binary star system and the prototype of the Cepheid variable stars – the closest of its type to the Sun.

This star pulses every 5.36634 days, causing its stellar magnitude to vary from 3.6 to 4.3. But that’s not all! Its spectral type varies, too – going from F5 to G3. Try watching it over a period of several nights. Its rise to brightness is much faster than its decline! With a telescope, you will be able to see a companion star separated from Delta Cephei by 41 arc seconds.

Are you ready to examine two red supergiant stars? If you live in a dark sky area, you can see these unaided, but they are much nicer in binoculars. The first is Mu Cephei – aka. Herschel’s Garnet Star. In his 1783 notes, Sir William Herschel wrote: “a very fine deep garnet colour, such as the periodical star omicron ceti” and the name stuck when Giuseppe Piazzi included the description in his catalog.

Now compare it to VV Cephi, right smack in the middle of the map. VV is absolutely a supergiant star, and it is of the largest stars known. In fact, VV Cephei is believed to be the third largest star in the entire Milky Way Galaxy! VV Cephei is 275,000-575,000 times more luminous than the Sun and is approximately 1,600–1,900 times the Sun’s diameter.

If placed in our solar system, the binary system would extend past the orbit of Jupiter and approach that of Saturn. Some 3,000 light years away from Earth, matter continuously flows off this bad boy and into its blue companion. Stellar wind flows off the system at a velocity of approximately 25 kilometers per second. And some body’s Roche lobe gets filled!

For some rich field telescope and binocular fun from a dark sky site, try your luck with IC1396. This 3 degree field of nebulosity can even be seen unaided at times! Inside you’ll find an open star cluster (hence the designation) and photographically the whole area is criss-crossed with dark nebulae.

For a telescope challenge, see if you can locate both Spiral galaxy NGC 6946 – aka. the Fireworks Nebula – and galactic cluster NGC 6939 about 2 degrees southwest of Eta Cepheus. About 40 arc minutes northwest of NGC 6946 – is about 8th magnitude, well compressed and contains about 80 stars.

More? Then try NGC 7023 – The Iris Nebula. This faint nebula can be achieved in dark skies with a 114-150mm telescope, but larger aperture will help reveal more subtle details since it has a lower surface brightness. Take the time at lower power to reveal the dark dust “lacuna” around it reported so many years ago, and to enjoy the true beauty of this Caldwell gem.

Still more? Then head off with your telescope for IC1470 – but take your CCD camera. IC1470 is a compact H II region excited by a single O7 star associated with an extensive molecular cloud in the Perseus arm!

Yes, Cepheus has plenty of viewing opportunities for the amateur astronomer. And for thousands of years, it has proven to be a source of fascination for scholars and astronomers.

We have written many interesting articles about the constellation here at Universe Today. Here is What Are The Constellations?, What Is The Zodiac?, and Zodiac Signs And Their Dates.

Be sure to check out The Messier Catalog while you’re at it!

For more information, check out the IAUs list of Constellations, and the Students for the Exploration and Development of Space page on Canes Venatici and Constellation Families.

Sources: